Two Writers — Albee and Kinsella — Depart the Same Day

By • September 19, 2016 0 1112

It’s hard to connect one of America’s greatest playwrights, an examiner of the terrors of modern life, with a writer made famous by a novel about a magical baseball diamond, except for the fact that they both died on the same day, Sept. 16.

The author of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” fame was 88 and the author of “Shoeless Joe” was 81.

I mention “Virginia Woolf” because that play cemented Edward Albee’s particular genius and talent, to be sure, but also because the movie version — which starred Hollywood’s calamitous celebrity couple Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, affectionately known as Liz and Dick — gave him a more enduring and broader fame in the popular mind.

The title “Shoeless Joe” refers to legendary baseball player Shoeless Joe Jackson of the 1919 Chicago White Sox, a team that lives in infamy as the “Black Sox” because some of its players helped throw the World Series (although Jackson apparently did not do so). “Field of Dreams,” the 1989 movie version of W.P. Kinsella’s lyrical book, was a star vehicle for Kevin Costner at the height of his square-jawed game.

The comparison is not meant to suggest that Kinsella is an equal of Albee in terms of literary value, but to point out that, while plays and novels of literary value are not for everyone, movies (and not always great ones) are forever.

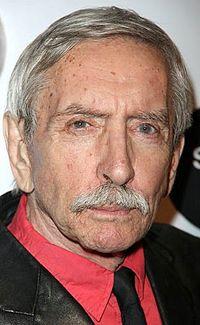

Edward Albee, 88

“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” burst on the national theater scene like a loud and loudmouth bomb, thrusting Albee, already the subject of quite grandiose and serious chatter, into the ranks of important American playwrights, notably Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, still working contemporaries, and Eugene O’Neill, the playwright Albee most resembles.

“Virginia Woolf” was not quite “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” but it was a cathartic, warlike long night of terrifying games (“Hump the Hostess” comes to mind), a battle of couples and a battle of the sexes with four protagonists: George, a defeated professor; Martha, his sharp-tongued wife; and their guests, an ambitious young professor and his nervous wife.

The original production starred Uta Hagen and Arthur Hill as the battling older couple, while Liz and Dick — under the direction of Mike Nichols — did the honors in the film. It is revisited time and time again. Kathleen Turner and Bill Irwin did star turns in a touring production, Arena Stage hosted a sterling production in recent years and Holly Twyford will star in an upcoming Ford’s Theatre production in the spring.

The play was a smash. It was considered for the Pulitzer Prize, then rejected due to its jaundiced view of the institution of marriage. Albee did win Pulitzers, but somehow the Nobel Prize eluded him.

By the time of “Virginia Woolf,” with plays like “The Zoo Story,” “The Sandbox,” “The American Dream” and “The Death of Bessie Smith,” Albee had already begun to enter another pantheon: modern absurdist playwrights, a territory occupied by Eugène Ionesco, Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter.

“A Delicate Balance,” a sad, tense, dark view of the upper middle on the road to losing their bearings, followed, along with “Tiny Alice” and adaptations of literary works like “Malcolm,” “The Ballad of the Sad Café” and Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita.” Albee also suffered through a decline that included alcohol and really bad reviews (see “The Man With Three Arms”).

But then he came back, with “Three Tall Women,” “The Play About the Baby” (a subtler, nastier meditation on “Virginia Woolf”) and, famously or infamously, “The Goat,” about an adulterous affair in which a man falls in love with a farm animal. Arena Stage did a scathingly tough, funny and oddly melancholy production; it saw a number of people walk out during intermission, often a sign you’re doing something right.

Albee showed us that it’s not easy for modern folks to find their way, navigating the road and seas where love and obsession and its counterpoint, loneliness, intersect. His landscape — unlike, say, Tony Kushner’s ambitious explorations of the whole world — was interior, next to our frightened and wildly beating hearts.

W.P. Kinsella, 81

Kinsella had no such ambitions, and his gifts shone most brightly around 1980. He wrote “Shoeless Joe” when he was 46, and it became, if not an instant hit, a slowly rising best seller, no doubt picked up by baseball fans, who scour the books and the daily box scores like blind men reading a Braille version of the bible.

One assumes there are millions of baseball fans, old, very old, young and somewhere in between, who can instantly access memories — real or not — of people they barely or never saw, home runs they only heard about over the radio and something as simple as a gimpy, lumbering Kurt Gibson hitting a walk-off home run for the Dodgers. People who care about such things are also full of lore of the Babe Ruth Yankees, the Bambino-accursed Red Sox and the Cubs who could, yes, could, win the World Series at last.

“Shoeless Joe,” which is also about fathers and sons and lost connection and redemption, sure enough, is about a dreamy farmer with a calling. To the bemusement of his patient wife and the horror of his practical brother, he has heard a voice from nowhere tell him to build a baseball field amid his Iowa corn: “If you build it, he will come” — he being Shoeless Joe or perhaps the farmer’s late father. And so he does, complete with lights.

If you’re the least bit sentimental, or crazy about baseball, which I admit to, there is no better moment in the movie than when the hero’s little daughter sidles up to him at the dinner table and says: “Daddy, there’s a man in your field.”

Be that as it may, it’s a lovely book celebrating not only baseball, but small-town and rural life. It may not have been so reflective of Kinsella himself, however. He said his aim as a writer was to make money. With “Shoeless Joe” and the movie rights, he probably succeeded, though not so much with equally sweet books like “The Iowa Baseball Confederacy” and “Box Socials.”

But thanks to the plays and the novels, and their movie versions, we’ll always have Joe (or Ray Liotta) marching in and out of an Iowa cornfield, barefoot, and we’ll always have George and Martha, in black and white, bigger than life.