At the Hirshhorn: Kusama’s Meditative Carnival

By • March 8, 2017 0 558

The hype was staggering from the moment it was announced. The Hirshhorn would mount the first Washington exhibition of Yayoi Kusama, the radical Japanese artist who has dominated the worlds of fashion and fine art for more than half a century.

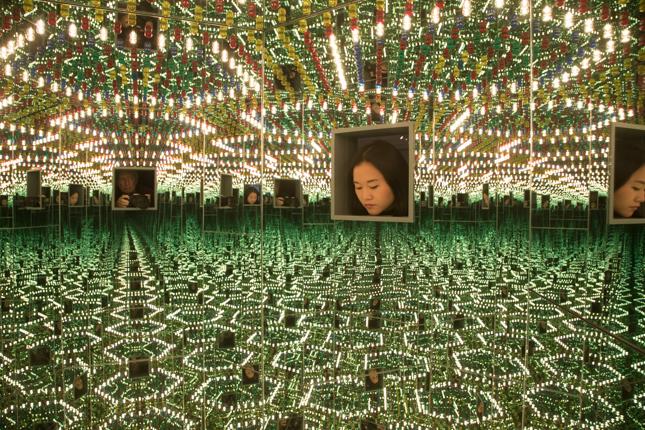

The show would focus on her “Infinity Mirror Rooms” — contained, mirror-lined spaces in which viewers are immersed endlessly within strange and magical landscapes, of glowing yellow polka-dot pumpkins or of small lights that float in the darkness like a heavenly procession of Chinese sky lanterns against a black sea.

It is an exhibition tailored perfectly to contemporary audiences, offering not artworks but environments, experiences in which our bodies are the centerpieces. The “Infinity Mirror Rooms” make us instantly special. They are selfie meccas.

In a post-Enlightenment and largely secular culture, in which God has become the individual self, Kusama’s rooms are readymade shrines to our fundamental belief in our own exceptionalism.

That said, I loved this show.

I am not suggesting that everyone who visits this exhibition is a depraved egotist, nor that the show is a reflection of our collective moral bankruptcy. But in the same way that persons and objects that achieve massive popularity in the world of entertainment invariably fit into some sort of archetypal superstructure of belief systems or societal hierarchies, it is difficult when thinking about the “Infinity Mirror Rooms” to ignore the very real presence of this idea.

The show is also whimsical and lovely on a purely experiential level, a meditative carnival in the spirit of Lewis Carroll. The “Infinity Mirror Rooms” live up to expectations in almost every way, engulfing the viewer in surreal dreamscapes of unapologetic joy.

(It is only fair to mention that as a member of the press I attended an early showing with very short lines and a full minute in each room, double the amount of time regular visitors have. After waiting in line for two hours, the rooms might be less of an encompassing theater of rapture and more like a quick thrill in a strenuously crowded theme park.)

Kusama is a fascinating artist. For one, she is an octogenarian Japanese woman, which alone makes her success unprecedented in contemporary culture. Her mere existence should be applauded, both for what she has achieved and for all it stands for in terms of women and alternative cultural traditions staking claims to art history. Throughout her career, her work has remained subversive, unique and groundbreaking.

For a time, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, her popularity was second only to Warhol in the United States. This has largely been forgotten due to her permanent return to Japan. In a sort of self-prescribed isolation, she has lived and worked in a mental hospital voluntarily since 1977.

Kusama is a performance artist, sculptor, painter and fashion designer of the highest order, all of which is deftly laid out in this pseudo-retrospective.

Yet this all seems rather incidental to the singular experience offered by her “Infinity Mirror Rooms” — and I mean that in no way as a criticism. It is just a testament to the power of her work and the rarity of her vision.

In a video in the first gallery, we are introduced to Kusama through an interview. She sits in a red wig and pink polka-dot dress, surrounded by her bright paintings and cactus sculptures, which are like Mexican alebrijes. She is both Queen and jester of her domain. And what does she have to say to her throngs of admirers?

“Pumpkins are humorous objects that also fill people with warm intentions,” she says. “Humor puts our minds at ease.”

She is unfettered by the historical and cultural implications of her work, perhaps uninterested or wholly unaware. But when dealing with such a wonderful artist, what does it really matter? What does any of it matter, save for the unforgettable experiences that she has forged for us all?

The exhibition is a cultural landmark and Kusama is an international treasure. Amidst the roiling cultural climate to which this show has been born, perhaps that is simply enough.