The Freer/Sackler, Reinvented Part 2: The Sackler

By • November 8, 2017 0 778

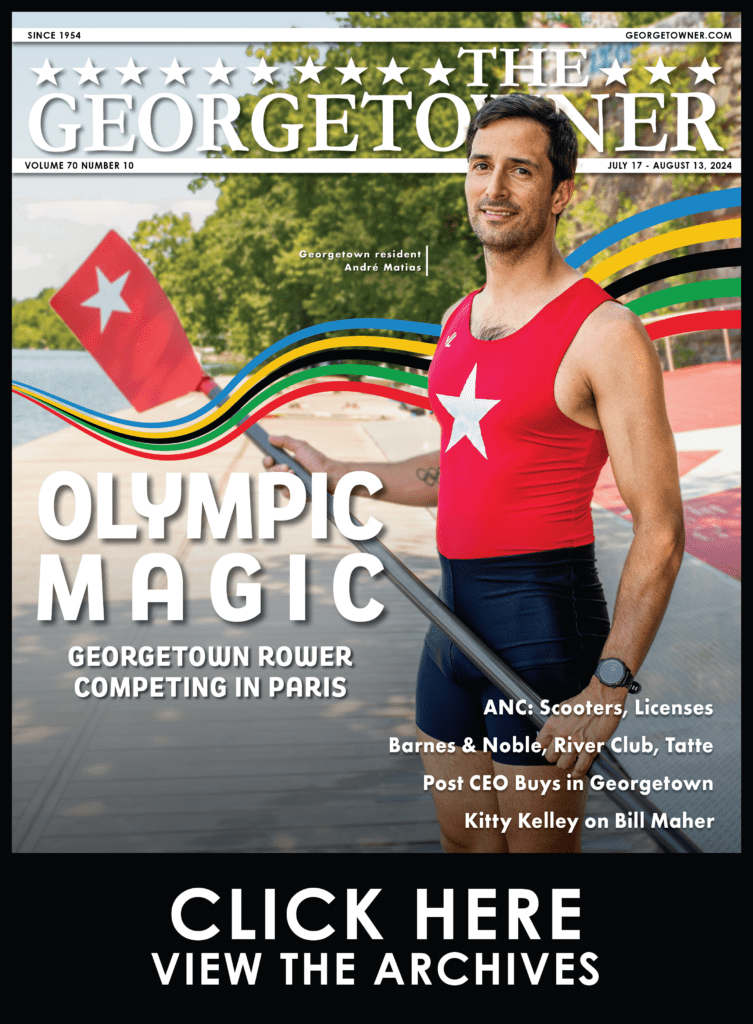

After nearly two years of renovations, the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery reopened Oct. 14. Part 1: The Freer appeared in The Georgetowner’s Oct. 25 issue.

It has been a tumultuous month for the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. On Oct. 14, after closing for the summer, the gallery celebrated its grand reopening in conjunction with the Freer Gallery of Art. Every major space was reinstalled with new exhibitions, displaying sculptural treasures — felines of ancient Egypt, Nepalese Buddhist shrines, Indonesian gods, bells from China’s Bronze Age — in innovative and engaging ways.

Then, on Oct. 30, the New Yorker published an article detailing the Sackler family empire’s ruthless and manipulative marketing of OxyContin and other prescription painkillers over the past 50 years, which built their billion-dollar fortune — and arguably caused the opioid epidemic.

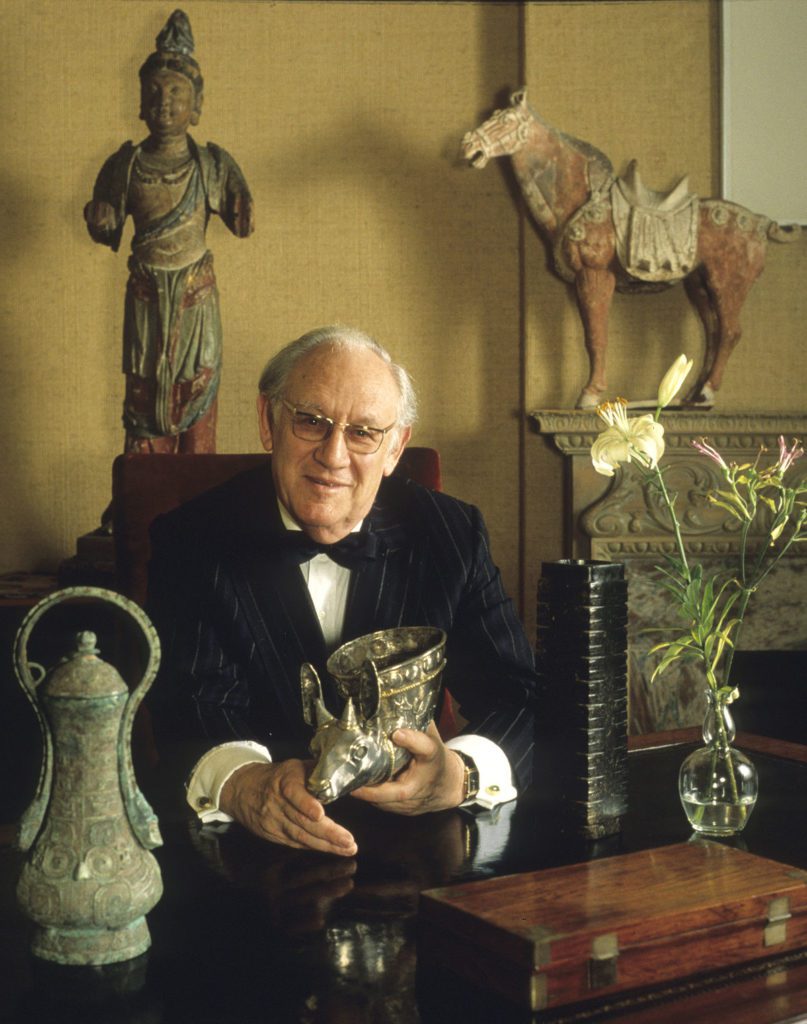

The Smithsonian released a statement addressing the controversy, asserting that the Sackler Gallery was named in 1987 for Arthur Sackler in recognition of his foundation’s gift of “an unparalleled collection of Asian art and a financial contribution toward construction of the building.”

Though sensitively veiled, the implication is twofold: First, this gift came personally from Dr. Sackler, not from Purdue Pharma, the privately held pharmaceutical company he built with his brothers, whose practices are the target of this scrutiny. Second, the Sackler Gallery opened in 1987 — Arthur Sackler died in 1987, four months before the museum opened — and OxyContin was not introduced to the market until 1996. In this sense, both the man and the gallery are ostensibly clear of any direct financial ties to the present-day opioid crisis.

The Sackler name is unavoidable throughout the art world. There are Sackler Wings at the Met and at the Louvre. Harvard has an Arthur M. Sackler Museum and the Guggenheim has a Sackler Center for Arts Education.

That a family should build such contradictory legacies is a troubling and paradoxical dilemma, if hardly unprecedented. Incredibly, the Sackler Gallery’s neighbor and architectural twin, the National Museum of African Art, suffered a damaging setback late in 2014, when it opened an exhibition featuring the collection of Bill Cosby just weeks before the numerous rape accusations came to public attention.

But let us not punish the child for the sins of the father. The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery is a sanctuary for the beauty of artistic achievement, antithetical to the ugliness on which the Sacklers built their fortune. The museum lends a voice to the cultural heritage of underrepresented countries that are critical to our national identity. Asian Americans have hugely defined our country throughout the 20th century, yet they are superficially understood and grossly neglected in our popular culture and educational systems. The Freer/Sackler is their cultural bullhorn in the nation’s capital.

The ways in which the Sackler contributes to public understanding of and engagement with Asia are on full display in the new galleries, which focus on creating environmental experiences to immerse audiences in the context of each artwork. This goes beyond explaining history — it sparks the sensation, wonder and curiosity of discovering a foreign landscape.

A modest but powerful gallery of Southeast Asian art marks the first dedicated exhibition for these countries in more than a decade. A carved stone Cambodian goddess figure stands at its center: Uma, the Hindu goddess of fertility, love and devotion. Drenched in warm light, she stares beyond the horizon with a Mona Lisa smile. A large-scale photograph against the back wall engulfs her columnar form in the faint glow of dense jungle heat, revealing a terraced, pyramidal temple rising from the wildness of the rainforest. A Khmer temple creates a powerful statement in the tropical landscape, and the gallery display allows you to experience the potency of the sculpture against the backdrop of its native environment.

“Resound: Ancient Bells of China” is a multisensory masterpiece of an exhibition. As artifacts, the bronze bells are like divine alien monoliths, austere yet ornate, with the oxidized surfaces of intermingling rust and green decorated with a geometry of dragons, birds, pattern blocks and knobs.

Echoing through the galleries, the low, cavernous hum of the bells is mesmerizing. To be clear, one does not simply whack a 2,500-year old bell with a drumstick. The museum scanned the bells to determine their acoustical properties and commissioned three composers to create soundscapes from the recorded tones of the ancient instruments. The soundscapes overlap with each other, and the effect is trancelike. Using a large touchscreen that translates the notes to a piano keyboard, you can even “play” the bells.

There is an exhibition on the Buddha throughout Asia so sweeping and ambitious that it is hard to know where to even begin. “Encountering the Buddha” brings together more than 200 artworks spanning two millennia, video footage of ritual prayer traditions, interactive maps and engrossing contextual displays that explore Asia’s rich and diverse Buddhist heritage. The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room is a symphony.

The reputations of public institutions are hard-won over time, yet today’s court of public opinion is savage and alarmingly swift. Ultimately, it might prove imperative for the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery to change its name. If the arts and humanities are expected to lead the moral charge of humanitarian empathy and cultural awareness, it is probably unwise for one of its representative institutions to hold onto a name associated with a legacy of peddling drug addiction and a death toll of 200,000.

The Sackler Gallery is not its namesake, and the Smithsonian should act aggressively to make that clear. I trust that, as a steward of history and cultural identity, the museum will have the courage to acknowledge its own.

The measure of human suffering and corruption is balanced by our capacity for grace, benevolence and beauty. The Sackler Gallery stands unmistakably for the latter.