Surprises, Tears at Museum of the American Revolution

By • November 8, 2017 0 1226

A daylong visit to the Museum of the American Revolution, which opened in Philadelphia in March, a block from Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, is full of surprises. Some exhibits bring on tears, others gasps of enlightenment; often visitors respond with an “I never knew that before,” complete with jaw-drop.

“Most Americans have very little knowledge of the American Revolution. There are no photographs. We want visitors, first of all, to believe that it all really happened,” said Scott Stephenson, vice president of collections, exhibitions and programming.

“The museum tells the story of the Revolution and the nation’s founding from the point of view of all the people living in America — the colonials of vastly different cultures, the American Indians and African slaves, the French, the British and the Spanish,” explained Stephenson. “All found themselves in the middle of a civil war.”

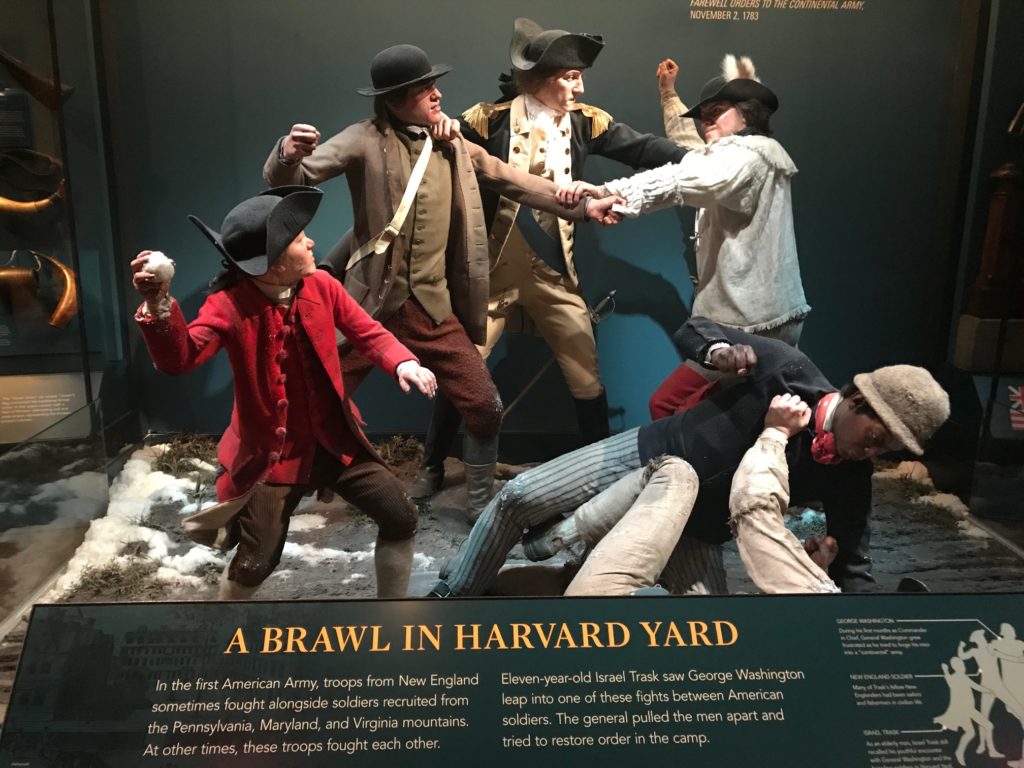

Cutting-edge digital technology allows visitors to see, feel, hear and understand the different stories of the Revolution, experienced through interactive displays, immersive narrative tableaux of life-size, highly lifelike figures and realistic soundtracks of debates, battles and everyday life.

The Dragoneers charge. Photo by Peggy Sands.

In one immersive theater, visitors watch delegates to the Continental Congress passionately debate whether to make a complete break with England. Others argue to appeal to King George to intercede on behalf of his “subjects” and order the English parliament to dissolve the stamp tax — the one that triggered the Boston Tea Party, which lit the fires of the Revolution.

In another gallery, visitors encircle a diorama depicting a tense meeting among chiefs of multiple Indian tribes. The passionate discussions about how to respond to the Revolution are relived: Should they aid the colonists in their fight against the British? Join the Continental Army (most joined the Brits, except for the Oneida)? Or “just let them fight it out and stay out of it,” as one chief says? Which will give them better trading deals in the end, protect their land, leave them be?

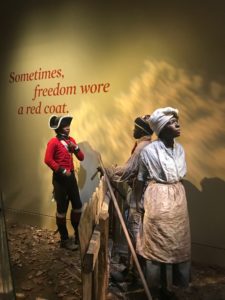

A pair of green-coated Loyalist Dragooneers gallop through one gallery on lifelike horses on their way to stopping colonial anti-British troops — sometimes with unmatched viciousness. Next to that, in a diorama, an African American boy stares over the fence at a youth, his own age and race, holding a rifle and dressed in the bright scarlet uniform of the British (King George promised slave-soldiers they would be freed if the British put down the revolutionaries).

African Americans fought on both sides. Photo by Peggy Sands.

But perhaps the most illustrative diorama of all, according to Stephenson, depicts Gen. George Washington breaking up a fight between American soldiers. It shows the tensions that arose due to the different cultures of soldiers from across the colonies: the South, New England, the Middle Colonies, New Amsterdam and Appalachia. “The tableau is worth thousands of words,” he said.

Stephenson has been working on the design and content of the exhibits for more than 10 years. “But, really, the museum is a 110-year-old start-up,” he said with a laugh. For decades, various historical groups have talked about the need for a museum to the American Revolution. Artifacts were collected and stored in various places around the East Coast.

A site was considered in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, home to a national historical park and a Museum of American History. But the site in Philadelphia came together in the 1990s with the cooperation of the Oneida Indian Nation and philanthropist Gerry Lenfest, who gave $50 million in matching funds.

“Through a land exchange, we were able to obtain the property at the center of historic Philadelphia at the site of the old visitor’s center,” Stephenson recounted. A $150-million fundraising campaign of private donors, including a $25-million endowment fund, was exceeded. The only government funding was an initial $30-million capital grant from the state of Pennsylvania. Designed and built from the ground up, the museum was completed debt-free.

“We are adamant about saying that the museum is not a permanent display, but has a core collection that is flexible,” Stephenson commented. Display cases, features and activities will change; different stories will be highlighted.

Arguably the most poignant display of all is Gen. George Washington’s war tent. In a dedicated theater, visitors watch a wall-size film depicting how the tent came to symbolize the general’s grass-roots commitment to the war and to the nation that came into being. Preserved by generations of the Custis and Lee families, the tent was carefully stored at Valley Forge. When the film ends, the screen disappears and, suddenly, there in front of the audience is the actual tent.

Stephenson often asks visitors, especially children exiting the museum, “What did you like best?” Typical is the response of one 10-year-old: “The tent,” she said immediately. Then she added, reluctantly: “I … I … I almost cried.”

The Museum of the American Revolution can be seen as the ultimate memorial to the first American veterans — veterans as diverse as those today, of every race, creed, religion and political belief — who fought for their vision of the American nation. Although Philadelphia held its Veterans Festival and Parade Nov. 5, the Constitution Center on Independence Mall is offering free admission on Veterans Day, Saturday, Nov. 11. Following a flag-raising at 9:15 a.m., there will be a wreath-laying ceremony, a military muster and a USO concert, with talks and family activities throughout the day.