Sometimes, monsters really do die.

They are not deathless, they stop visiting in the night, unbidden, they are, at long last, bidden to disappear into the future as past.

They died.

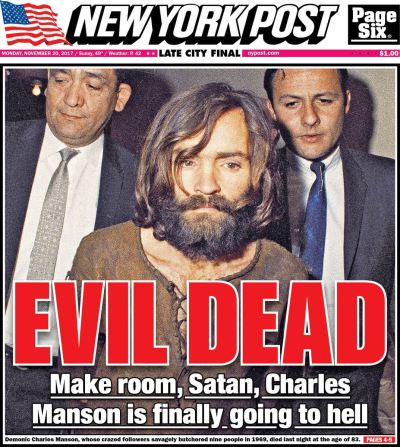

Charles Manson died. This most unnatural of men was said to have died of natural causes at a hospital in Bakersfield, California. He was 83 years old, and looked in one of his latest pictures, like a prophet looking for another cause, bald and glaring.

Once he was a would-be singer, songwriter, a very California-for-the-times-goal description. What he was was a cult leader, an instigator, a murderer and killer, who cast a spell over a group of young drifters and grifters—women and men—already spellbound.

Among them—they were called the Manson family—in two horrifically unforgettable acts of carnage and violence, they invaded two homes in Los Angeles, savagely killed five people in one, two in another. They spilled blood, left bloody messages and left an imprint on the dreams and minds of the haunted, feverish denizens of California, the country, us, one and all.

Manson spent some time in San Francisco in the Haight Ashbury during the summer of love in the 1960s, where he began gathering followers. His true bearing and locus were Southern California, Los Angeles, the wine and roses, drug-addled, guitar riffed world of Hollywood, where drifters, dealers, hucksters and young women of no particular direction, almost complete unknowns rubbed if not elbows at least sleeves with people of showy power.

Hollywood—old and new—pervades the sick saga of the Manson world like acid rain, where the rock-pop music world had taken root in mansions of stars who had faces once, in the bong and hash parties where producers looked at the scribbling of would-be song writers like Manson, who dreamed dreams of Helter Skelter and racial annihilation. He brushed sleeves with a Beach Boy, with Terry Melcher, a producer and the son of Doris Day.

Manson had been at various times a burglar, an auto thief, an armed robber, as well as a busboy, parking lot attendant, check forger and pimp. He was also a motivator of murder, “Helter-Skeltering” (taken from the title of the 1968 Beatles song) for his band of followers. For Manson, the act of murder was to order it, to inspire it. Their tally was nine murders in four locations. Among his followers were Susan Atkins, Charles “Tex” Watson, Lynette Fromme, Bobby Beausoleil, Steve “Clem” Grogan, Catherine Share, Sandra Good, Leslie Van Houten, Patricia Krenwinkel, Linda Kasabian.

On the night of August 8-9, 1969, Manson sent Atkins, Krenwinkel, Watson and Kasabian to what was known as the Tate home. Inside, they began a long, Walpurgis Night of slaughter and murder, killing movie star Sharon Tate, Abigail Folger, heiress to the coffee fortune, Voytek Wojciech, Hollywood hairdresser Jay Sebring and Steven Parent. Tate, who was pregnant, was the wife of director Roman Polanski, who was in Europe at the time. The following night, Manson and some of his followers drove to the home of Leno and Rosemarie LaBianca, selected randomly, resulting in the murder of the couple and bloody scrawling of “Helter Skelter” and “Death to Pigs.”

The family—Manson and the rest—were eventually caught, followed by a sensational trial and bad dreams for everybody.

To many in the country, even in California, the Manson family and leader were symbols—of the worst of rock-n-roll, drugs, conspiracy, violence, overdoses, the whole circus of sex-drugs-and-rock and roll and ultra violence. They inspired music, Marilyn Manson, books and the recent TV series “Aquarius,” which tried to resurrect the era, the time, the rhyme and reason of the horror.

The acts and crimes invaded our dreams. If you lived in California during and after—this was the time of the Patty Hearst kidnapping, Altamont and the Zodiac Killer—nothing surprised you thereafter.

Sooner or later, in spite of it all, monsters die as he did.