‘Outliers’ at the National Gallery

By • March 7, 2018 0 623

Great art — or, at least, important art — can result from a purely rational process. The precisely delimited, flat-colored paintings of Mondrian and Ellsworth Kelly, for instance.

But more often, work that succeeds in capturing an emotional experience in visual terms and transmitting it from artist to viewer has an irrational component, meaning the unconscious mind has come into play. Think of Goya, Redon, van Gogh, Rothko, Pollock, Bourgeois.

Sometimes this quality appears in the work of artists who follow their own paths in isolation, perhaps not even thinking of themselves as artists. And, in some cases, influential work (as well as much unsuccessful art) is the product of an altered or a nonconventional mental state. Without trying to sort out the posthumous diagnoses of van Gogh’s condition, it’s fair to say that if he hadn’t been canonized (rightly) as one of the greatest Post-Impressionists, he might have been labeled a folk, naïve, primitive, self-taught or visionary artist.

Rather than endorse these pigeonholing adjectives, the major National Gallery of Art exhibition “Outliers and American Vanguard Art,” on view through May 13, seeks to give artistic outsiders the inside track. The show “introduces the term ‘outlier’ in order to propose a new conception of creators at a distance from the aggregate who have agency: that is, their position at a remove is often a preferred location, a place of strength.” (Whether Malcolm Gladwell gave his blessing is unknown.)

With a view to eliminating distinctions between the trained and the untrained, the cosmopolitan and the provincial, the agnostic and the religiously inspired, even — in politically incorrect terms — the sane and the insane, the exhibition’s curator, the National Gallery’s Lynne Cooke, has intermingled works by artists of very different backgrounds.

The organizing principles for this impressively sprawling show, comprising more than 250 works, are formal and chronological kinship. Cooke — an Australian who received her Ph.D. from the University of London’s Courtauld Institute — has identified “three moments of social, political, and cultural upheaval when the intersection of self-taught artists with the mainstream has been at its most fertile: the interwar years, particularly the aftermath of the Great Depression, through World War II; the ‘long’ decade of the 1970s, in the wake of the civil rights, feminist, gay liberation, and countercultural movements; and a period beginning in the twilight of the twentieth century, when the long-held division between schooled and unschooled makers finally proved untenable.”

Traveling to the High Museum in Atlanta and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the exhibition is likely to take its place on a roster of inclusionary projects cited in the accompanying text: the Whitney’s “Early American Art” of 1924; the Federal Art Project’s Index of American Design, founded in 1935; Alfred Barr’s “Masters of Popular Painting” of 1938 at MoMA; the Corcoran’s “Black Folk Art in America: 1930–1980” of 1982; and traveling exhibitions of Gee’s Bend quilts.

Oddly, the exhibition does not refer to two other museums that led the way: the American Folk Art Museum in New York, which held its first exhibition in 1961 and launched its contemporary center with a spectacular exhibition of Chicago janitor Henry Darger’s scrolls of traced little girls at war in 1997; and Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum, which opened in 1995 and expanded in 2004.

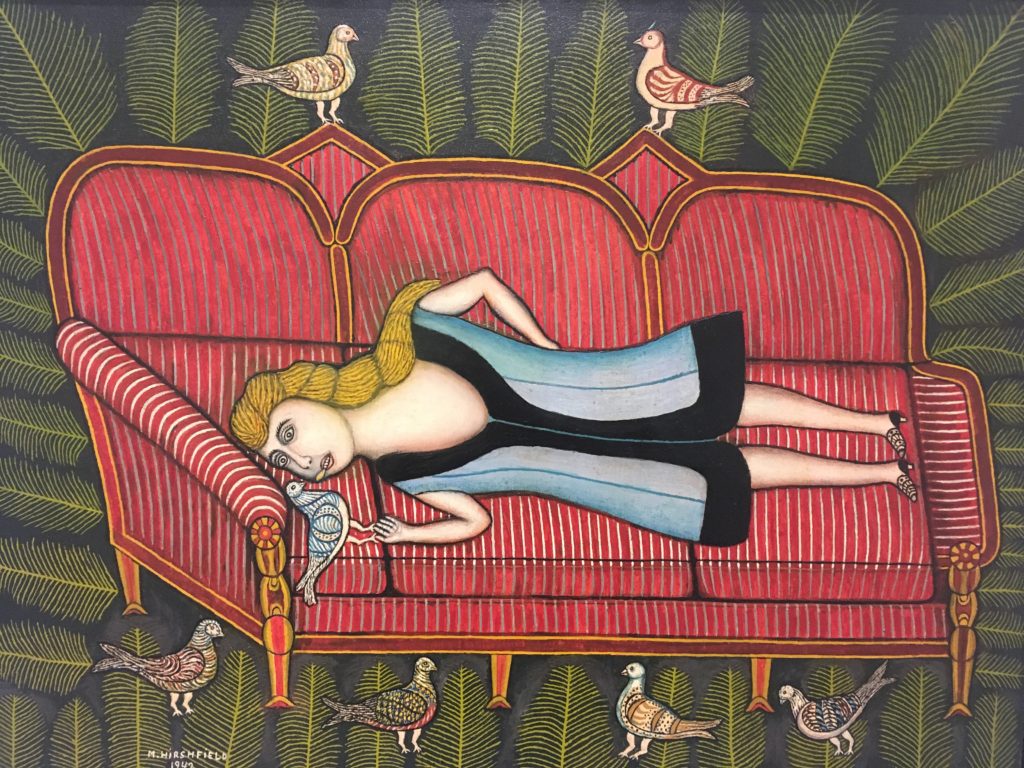

The very bizarre Darger is here, as are classic “primitives” like Henri Rousseau and increasingly appreciated African American artists such as sculptor William Edmondson and painters Horace Pippin and Sister Gertrude Morgan. There are also works by highly trained and sophisticated artists who were inspired by self-taught artists: Marsden Hartley, Florine Stettheimer, Charles Sheeler, Jacob Lawrence and Betye Saar, for example.

In fact, more than 80 artists are represented. Though having so much to see, enjoy and learn from is a plus, at times the abundance seems to muddy rather than clarify a complex topic. It also causes one to ask “Why him (or her)?” and “Why not her (or him)?” But perhaps this stimulating effect was intended.

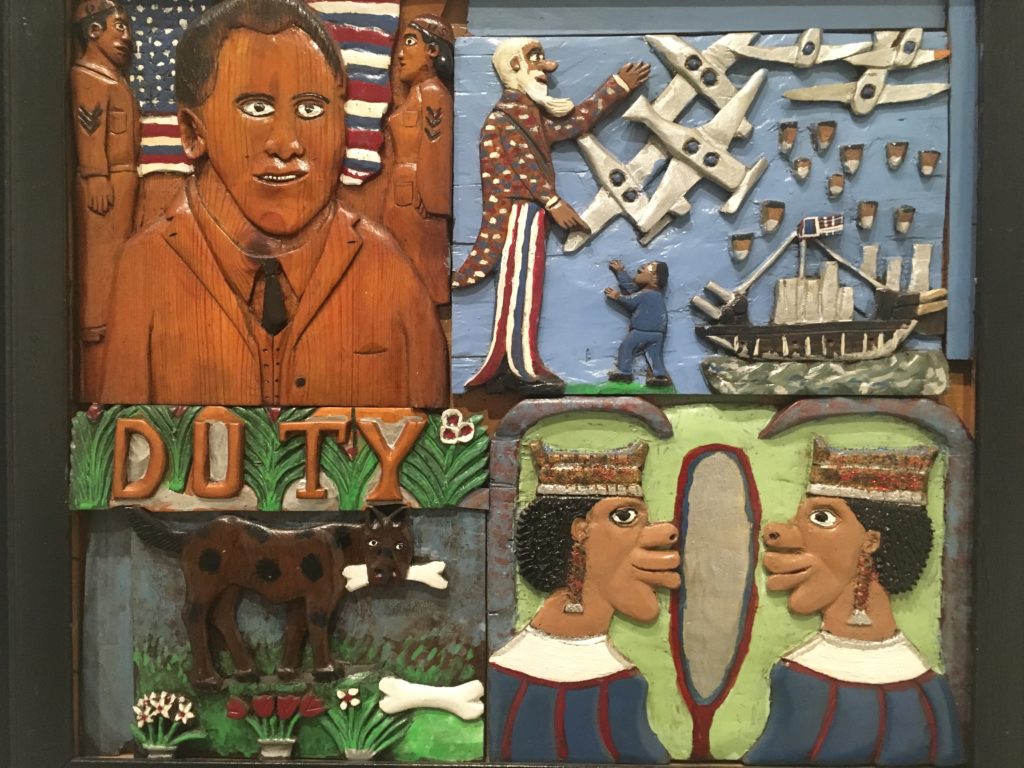

“Pearl Harbor and the African Queen,” c. 1941. Elijah Pierce.

“Loving Couple,” 1967. Gladys Nilsson.