Neil Simon’s Gift to Us

By • August 30, 2018 0 935

Last weekend was not a good one for laughter.

On Saturday, Aug. 25, Sen. John McCain, an icon of an American man of courage and principle, died of brain cancer only a day after it was announced that treatment had been stopped.

Flood waters raged through city streets in parts of Hawaii.

On Sunday afternoon, there was another one of those irrational, horrible shootings at a video game tournament in Jacksonville, Florida, with three dead, including the shooter, and nearly a dozen wounded.

That same afternoon, Neil Simon died at the age of 91.

That’s when a flood of appreciations and tributes began about Simon’s 30-some plays, numerous screenplays and considerable television work, for which the principal memory is that of the sound of laughter.

Simon, the bespectacled Jewish New Yorker, it turned out, could make people laugh, a gift from which he profited enormously, garnering praise, honors galore — Tonys, a Pulitzer Prize, a Mark Twain Award, a Kennedy Center Honor — and a popularity with audiences and the public that was, in terms of numbers and affection, unrivaled.

It was also a gift that sometimes, according to the odd critic or two, undermined Simon and irked him, because laughter was akin to answering the call of “Let me entertain you.” It related to the very necessary wing of American theater that counted ticket sales, which, in Simon’s hit-after-hit case, were in the millions. Commercial success of the kind he garnered were also sometimes frowned upon and sneezed at by the self-proclaimed serious wing of the American theater, which embraced Mamet and could endlessly discuss the Eugene O’Neill one-act “Hughie.”

In truth, Simon’s plays were often and almost always primarily funny — he had a preternatural way with one-liners — but, also in truth, his humor, his funny stuff, the funniest plays could get under your skin because the experience of watching the characters and hearing them talk and kvetch, whine and opine, attack and defend were like inhabiting a mirror that contained yourself.

Simon could wear both masks of the theater, the ha-ha and the boo-hoo. It’s the funny that you remember first, though, because the funny is about character, and about life’s difficulties when human beings are confronted with obstacles — and with each other.

Consider that five-story walk-up which had to be overcome, maneuvered over and up, in Simon’s first really big hit, “Barefoot in the Park,” a rom-com about the first blush of sticky love for a pair of newlyweds, dealing with each other, parents and neighbors. Part of the humor is pure slapstick that reveals character: how to navigate the five flights of stairs, the hole in the skylight and the empty space of the newlywed apartment (not to mention mom’s suitor).

The movie version — and there were almost always movie versions, and even movie originals, in Simon’s work — starred Robert Redford and Jane Fonda. Redford had done the Broadway original with a daffy, determined and fetching Elizabeth Ashley as his wife.

Most of Simon’s plays were about the rough edges of relationships under the stress of situational tensions, fresh love or fresh love becoming familiar, followed by changes, aging and time its own self. We — that is to say students of life post-college, couples, parents and veterans and children of divorce — could hear loud echoes in many of the plays, echoes that made us, yes, laugh, again and again, often uncomfortably, often out loud.

There’s “Laughter on the 23rd Floor,” the 1993 autobiographical play about Simon’s life as a writer among a group of writers working for the 1950s television hit “Your Show of Shows,” with the genius if not genial Sid Caesar as star, sun and moon, a time when Simon rubbed ideas, words and shoulders with the likes of Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner. It is remarkably funny and not a little incestuous, in professional terms, but also a treasure if you’re old enough to have seen the product.

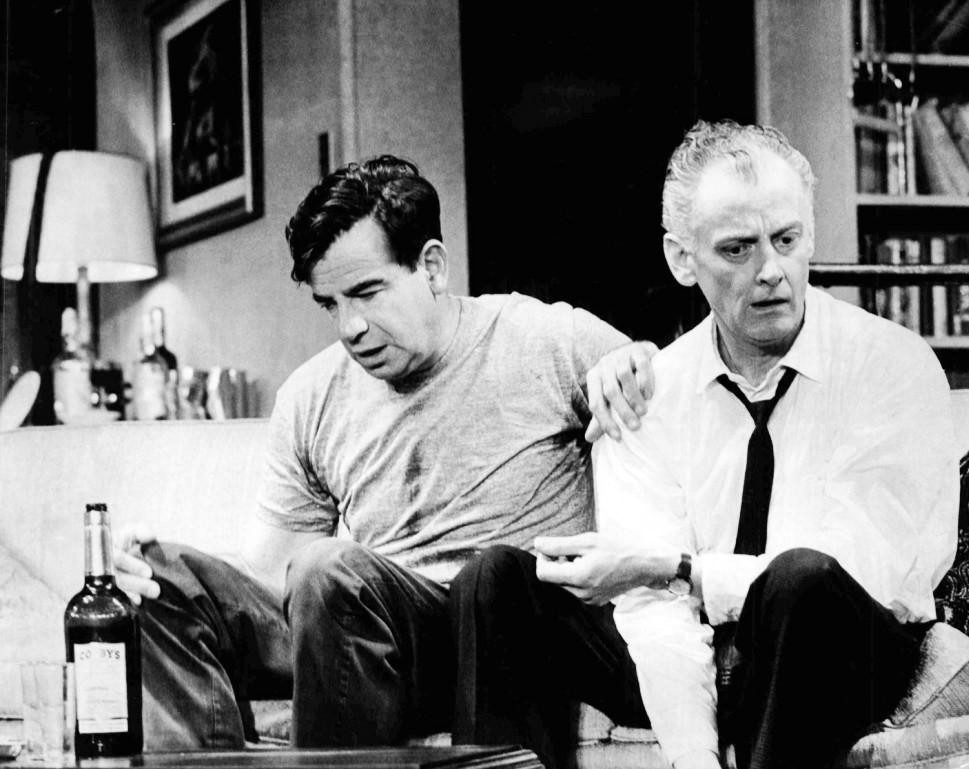

Then there’s “The Odd Couple,” a disastrous, painful theatrical illustration of opposites attracting that became a monster hit on Broadway in 1965, with Walter Matthau as the scruffy Oscar Madison rooming with neat-freak Felix Ungar, played by Art Carney. It became a huge movie hit with Matthau and Jack Lemmon and a long-running television series with Jack Klugman and Tony Randall. There was even a female version with Rita Moreno and Sally Struthers.

Joy and laughter of a different, familial sort are to be found in the trilogy of “Brighton Beach Memoirs,” “Biloxi Blues” and “Broadway Bound,” which chronicles the rise of Simon’s alter ego Eugene from childhood through military life through showbiz. The trilogy didn’t lack for laughter, but it had a different tone, the softer tone of well-remembered embarrassment and affectionate times.

Finally, there was “Lost in Yonkers,” which, if it didn’t put him in the O’Neill wing, put him in a theater wing all his own. It’s a touching, tough play with fully imagined characters — a rough, dysfunctional family that included a gangster, a full-bodied but mentally slow young woman finding herself and a grandmother who was an embittered survivor of Germany under Hitler, as well as two young boys. It, too, has its moment of laughter, but it is nothing less than a fine, emotionally powerful play, premiering with a cast that included Kevin Spacey, Irene Worth and Mercedes Ruehl.

Seeing the news of Simon’s death, I remembered laughter of all sorts: the guffaw, the broad burst of noise, the laughter that sounds like a soundtrack and the silent laughter, a knowing smile forming and slipping into memory.

The laughs are always going to come. Simon is gone, but we’re still laughing. With material like Simon’s plays and movies it’s hard not to, no matter what the times are like or what kind of weekend it was.