Books in a Noisy World

By • November 26, 2018 0 417

We live in a noisy world. The noise is ambient, in your face, in your head or in passing.

The volume on television seems always up even when it isn’t — the too-much interrupted talk of talk shows or reality shows from “Dancing with the Stars” to “Love After Lockup.”

We live in a noisy world. So: Sshhh! Please.

Contemplate for a moment the absence of noise, and moments where there is a triumphant preponderance of silence.

Let’s think books (or a book) or authors and writers or the caretakers of books: the cataloguers, the shelf arrangers, the perusers, the librarians. Let’s think about readers, sitting on a chair, glasses or not, moving from one page to another, the tactile fuzz of paper edges, the print itself and how sentences or lines arrange themselves on a printed page, languorously turn into paragraphs or present themselves as purposeful shapes in a poem.

Books are quiet but they nevertheless contain music, and the loudness of meaning.

Let’s talk about librarians, the caretakers and caregivers who now preside over what is rumored to be the passing or decline of books — not a “Fahrenheit 451” conflagration, but nonetheless an apparent reduction of interest and volume.

You would not be able to deduce a lack of interest when you contemplate the life and times of the Ronald Reagan-appointed 13th Librarian of Congress Dr. James H. Billington, who held that position for 28 years.

In a way, Billington — a thinker and teacher, an expert on Russian culture and an author as well as heading the national treasure house and storehouse of American cultural, educational, scientific, cultural and literary works, not to mention all manner of statistics and records — was a book. He contained, as Walt Whitman might have had it, “multitudes” within himself as overseer, educator, writer and consumer.

During his tenure at the Library of Congress, Billington — who died on Nov. 20 at the age of 89 — doubled the size of the non-digital collection, to more than 160 million items. He also led the inevitable creation of a new Library of Congress online, a broader, less stodgy and less bookish but more participatory resource. He said he wanted to “get the champagne out of the bottle.”

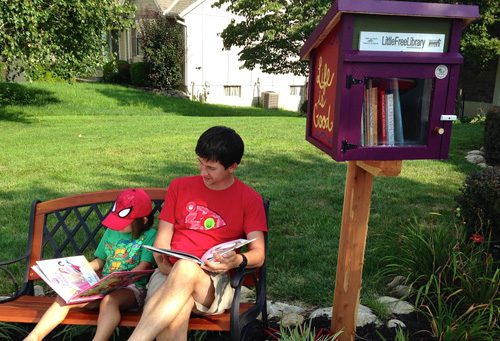

You could call Todd Boll, who died last month at the age of 62, a kind of librarian too. Boll was the inventor, creator and founder of the Little Free Library — a concept, the product of a generous spirit, that started from his Hudson, Wisconsin, home base. The first, created in 2009, was in memory of his mother, a schoolteacher and a big reader.

He built a box with a roof, a latch and a sign that said “Take a Book, Share a Book.” Inside, books were there for the taking.

The movement — that’s what it really became — soon spread. Little Free Libraries now number in the thousands. There are no real specs. They can look like birdhouses or a form of folk art, in which you can find New York Times fiction selections, worn paperbacks, so-called women’s fiction, history books, biographies, you name it.

There are quite a number in Washington, D.C., two in my immediate neighborhood. One is hidden on a side street behind a stately bush. Another is at Joseph’s House, the Lanier Heights hospice for the homeless in Adams Morgan.

These micro-libraries — which loose books like rare birds onto streets, town and cities across the country — seem to give the lie to the notion that books are a fading format. The Little Free Libraries are more like permanent yard sales of literature, kept up and safe from the weather by their owners.

Recently, I picked up a volume of poetry down the street, a well-worn copy of “A Book of Women Poets from Antiquity to Now: Selections from the World Over,” from Shocken Books, New York, first published in 1980.

If you are a reader — or even if not — it’s the kind of book that’s a find, to be kept and put in the family will, if there is one. It runs from Sappho to Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Sylvia Plath. Included is a generous offering of Emily Dickinson, as in: “I’m Nobody! Who are You?/Are you – Nobody – Too?”

Dickinson seems always to have been the provocateur of silence, of the sound next to silence and sometimes just before death. A quietude, if not a solitude, surrounds her and her life, a legend of reclusiveness.

The Folger Shakespeare Library, next to the Library of Congress at 201 East Capitol St. SE, will pay tribute to Dickinson on her birthday, Monday, Dec. 10, at 7:30 p.m. with a reading and conversation with Dickinson scholar Martha Nell Smith and poet and artist Jen Bervin, co-editor of “The Gorgeous Nothings: Emily Dickinson’s Envelope Poems,” which focuses on Dickinson’s late compositions on envelope scraps.

Words on paper — as opposed to envelopes — are the left-behind remains of writers, whose nemesis is the blank page, even on a computer. William Goldman, who died on Nov. 16 at the age of 87, did not leave many wadded up or blank pages of paper behind. He was a prolific novelist and writer of screenplays, the most dazzling of which was the screenplay for “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” perhaps the most thoroughly entertaining piece of movie fizz and star power — namely Paul Newman and Robert Redford — ever created. His novels were notable and best-selling: “Boys and Girls Together,” “No Way to Treat a Lady” and “Tinsel,” among others.

Sometime around the time you fall asleep, you pick up a book. You open to the last page from last night.

Sshhh.