Last Chance: ‘Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist’

By • December 27, 2018 0 4199

When it relocated to a new building on Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 2012, the Barnes Foundation — the incomparable, idiosyncratically hung art collection of Albert C. Barnes — acquired space for temporary exhibitions for the first time. The museum’s current special exhibition, “Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist,” closes Jan. 14.

The show is the first American exhibition devoted to Morisot in more than 30 years. Many of the nearly 70 paintings are from private collections, and having them in the same building as Barnes’s seemingly unlimited haul of Renoirs, Cézannes and Matisses is a plus, if not entirely fair to Morisot.

She greets us at the entrance in an enlarged photograph by Charles Reutlinger: serious-looking in a long dress, bare arms, gloves and a hat tied round her head, seated informally in the photographer’s studio on a sideways-turned chair, upholstered and fringed. One gets the impression that she has nothing to prove to herself or to those who understand the new art — only to the tradition-bound bourgeoisie.

The daughter of a government official, Morisot was raised in that upper middle-class, conservative milieu. But she studied with Corot, posed for Manet and married Manet’s artist brother Eugène in 1874, the year of the first exhibition by the group that became known as the Impressionists. Morisot was the only woman who participated, also showing work in all but one of the seven later Impressionist exhibitions.

One of her best-known paintings, “The Cradle” of 1872, from the Musée d’Orsay, dramatically frames a tender scene. The semitransparent netting over the cradle makes a bold white arc that confines Morisot’s sister Edma to a quarter-circle at upper left as she gazes at her baby daughter.

This juxtaposition of dark and light shapes resembles the manner of Morisot’s future brother-in-law. But unlike Manet, she abandoned black to pursue coloristic effects in such paintings as Cleveland’s “The Green Umbrella” of 1873, which could be mistaken for an early Monet.

Also Monet-like, but with looser brushwork, are two seascapes from 1875, painted during Morisot’s honeymoon with Eugène on the Isle of Wight. Here, and in a section titled Finished/Unfinished, is evidence for the curatorial claim that Morisot was not only a founder of Impressionism but engaged in “radical experimentation.”

In her paintings, including portraits, of the later 1870s and 1880s, she indeed seems to be exploring color and texture without being constrained by direct observation of her subjects or how light falls upon them. Some of these paintings, with parts of the canvas left bare, look more like pastels than oils.

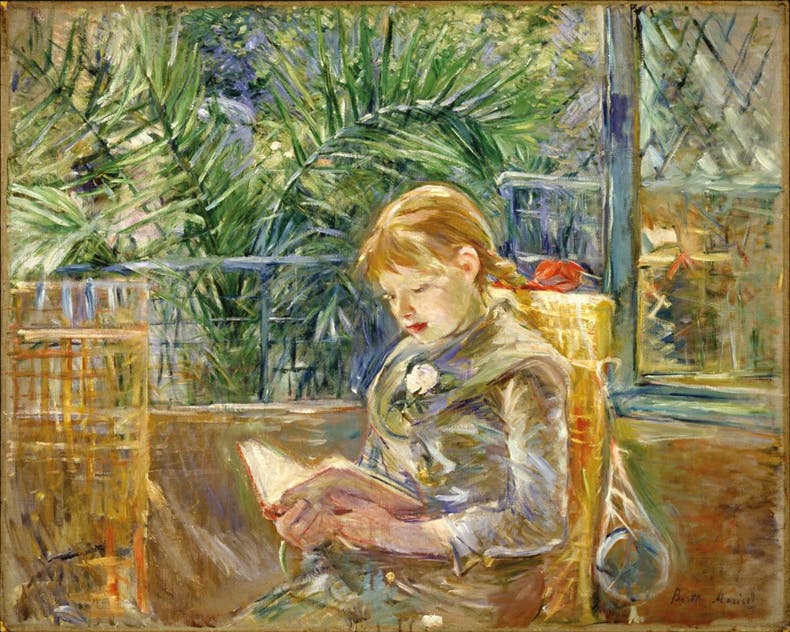

A high point of the show is the section titled Windows and Thresholds, one wall of which displays “On the Veranda” of 1884, from a private collection, next to “Reading” of 1888, from St. Petersburg, Florida. Both depict a young girl in front of a large window, but the red-haired girl in “On the Veranda” is Morisot’s daughter Julie while the less redheaded girl in “Reading” is a model. In different settings (palm fronds appear in “Reading”), these are variations on the theme of the merging of indoors and outdoors which became a Matisse, then Bonnard, signature in the early 20th century.

Two sections with more traditional paintings, Fashion and the Modern Woman and Women at Work, address the issue of how Morisot’s sex affected her subject matter and treatment of it. As a well-off Parisienne, she painted models in fashionable attire from the point of view of a wearer of such garments. There is none of “the male gaze” here, and only one nude in the exhibition. The working women she painted were usually her own maids, cooks and nannies. The exhibition text notes that, unlike her American-born near-contemporary Mary Cassatt — whose more linear, Japanese-influenced style was closer to Degas’s and who later exhibited with the Impressionists — Morisot rarely chose to paint scenes of mother and child (“The Cradle” is an exception).

The show concludes with a section titled A Studio of Her Own. After Eugène died in 1892, Morisot moved to an apartment in which, as usual, she had a home studio. Before she died, at age 54, in 1895, she had begun to paint in a ghostly, Munch-like style that had “visual affinities with the emerging symbolist aesthetic of the time.”

Having taken in Morisot’s oeuvre, one is left with a sense of her self-confidence, even fearlessness, as an artist, highly unusual for a woman in her place and time. If some of her experimentation did not lead to breakthroughs she was able to bring to maturity, that is the nature of innovation, to which this provocative exhibition rightfully and rewardingly calls attention.