‘Twelve Angry Men’ at Ford’s

By • February 6, 2019 0 1437

Movies will always remain essentially the same. Audiences may change, the dimensions of the screen may change — now you can stick one in your pocket or hang it on a wall — and the volume may change. But in the end, Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) will always, just before turning away, say to a shocked Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh), “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn,” and that’s that.

Plays, written for the theater, are the most fragile of things. They are subject to whims and fancies, the vagaries of casting and the visions of directors, the moods of audiences, the placement of a klieg light, the color of a dress, whether an actor is running a fever or just feverish. They change almost every day and night, and with every utterance of the same words by different actors.

Everything changes in every performance of a play, sometimes dramatically, sometimes merely by a slight change in inflection. That being said, you can see how a play like “Twelve Angry Men” by Reginald Rose, with a long history of performances and venues, might be affected by large changes in the structure and makeup of the cast.

The play first emerged on television in 1954, when the medium was undergoing an exhilarating dive into the creation of original dramas, written to be performed and broadcast live — works like Paddy Chayefsky’s “Marty” and “The Catered Affair” — on such shows as “Studio One” and “Playhouse 90.”

“Twelve Angry Men” was a hallmark of the genre, a play that focused tightly on the deliberations of an all-white jury deciding the fate of a young man accused of murdering his father with a knife. Taking an initial poll, the jury members find themselves with an 11-1 count for a guilty verdict. The lone holdout then begins in reasonable terms to question the evidence in detail, in the process creating doubt in the jurors on details of memory, personal prejudice — the accused is assumed to be a person of color — matters of timing and detail and so on, until he turns the jury around.

On television, especially, this was a tightly constructed play, and it was that way in what is now considered a classic film version with Henry Fonda — the ultimate moral and liberal American as fair and reasonable citizen — in the role of Juror #8, the lone holdout and persuader. Also in that cast were Ed Begley and Lee J. Cobb. A second version from 1997 featured Jack Lemmon and George C. Scott.

Live stagings were numerous too, including one in 2009 at the Kennedy Center starring Richard Thomas.

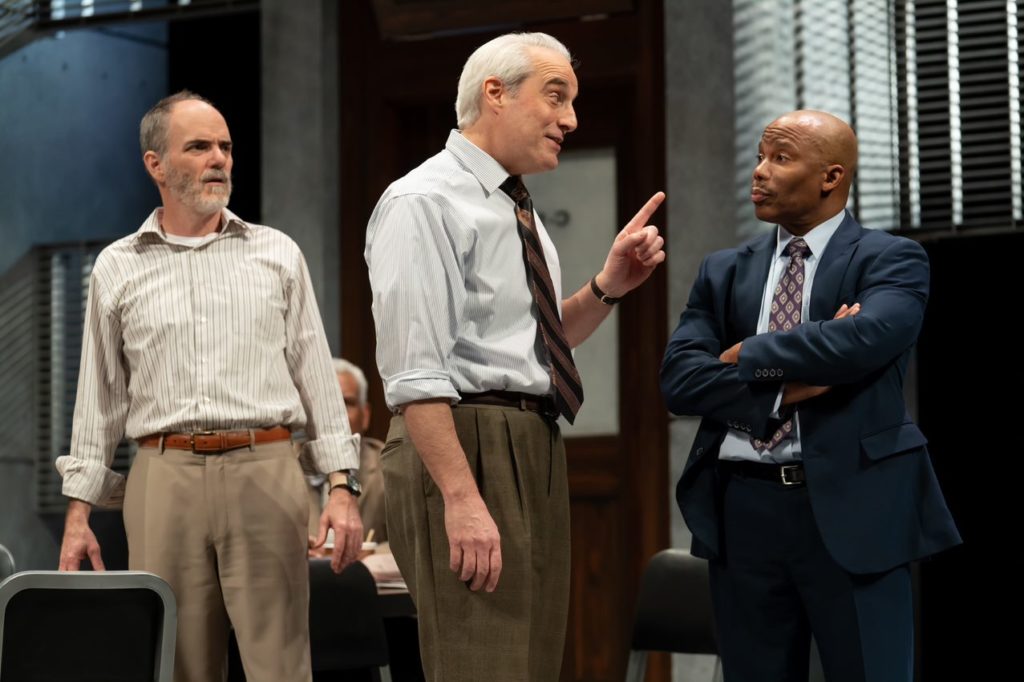

The Ford’s Theatre production, directed by Sheldon Epps and running through Feb. 17, has added another layer to the proceedings. Six members of the cast are African American.

In terms of language, the changes aren’t drastically dramatic. What happens, however, even as the play does as it always does — celebrate the democratic spirit if not the reality of American justice — is that race becomes very much a subtopic, if not the topic, of the play. This is as should be; the system as it stands today would not allow for an all-white jury, for one thing, although the 6-6 split seems dramatically convenient as much as it could be plausible.

Juror #8, the lone holdout, is played by black actor Erik King. He’s sharp-eyed and sharp-tongued and dogged, slowly poking holes into the evidence as all of them review it, from the plausibility of the view from a passing train, to the angle of a knife, to questions of vision, time and memory.

None of the evidentiary arguments are necessarily final or even 100-percent correct, but they raise what #8 pursues with a relentless spirit — the area of reasonable doubt, a hallowed legal concept of U.S. jurisprudence. That reasonableness is forsaken often, especially by the presence of Juror #10, a bigot and bully played with malignant bravado by Elan Zafir, who finally in the end succumbs, not out of principle but out of sheer fatigue, after exposing his bigotry and hatefulness, his pure racism, in an astonishingly frightening moment.

The cast mixes newcomers with Washington veterans like Lawrence Redmond, playing a fidgety juror eager to get to a basketball game, Craig Wallace as a voice-of-God African American who has his moments of passion and moments of quietude and Michael Russotto, in a moving, anguished portrayal of a man haunted by his personal experience.

The change in casting does something else. It lets you see the groups and subgroups of the jurors as they energetically arrange and rearrange themselves, the subgroups almost invariably coming together by race in different areas of the jury room.

What you get to see and hear in the dialogue is the prevalence of race in American today in a play that goes back to the 1950s — a transference that is shocking, more than the casual clichés spouted by a juror who’s in marketing or a football coach or a black character who’s a watchmaker and an immigrant.

Most of the jurors are treated with respect as individuals, until they begin to collide physically. When the arguments and insults flow, it’s as if you’re in a ring with a play called “Twelve Even More Angry Men.”