Getting the Vote: The Great Suffrage Parade of 1913

By • March 26, 2019 0 1417

Luckily, Monday, March 3, 1913, dawned bright and clear. It was cold, but that would only really be a problem for the barefoot dancers on the marble steps of the Treasury Department. Rain or snow would have been disastrous. A little chill could be expected in Washington in early March, and everything that could be expected had been planned for.

The marchers were set to gather at two o’clock near the James A. Garfield Monument on Maryland Avenue SW. Grand marshal Jane Burleson would lead them out into Pennsylvania Avenue at exactly three o’clock.

A daisy chain of trumpeters would pass the news down the parade route that the march was underway, and the fantastic allegorical pageant would begin on the Treasury steps. It would take Burleson and her attendants about 45 minutes to lead the procession the mile and a quarter from the Peace Monument in front of the U.S. Capitol to the site of the pageant.

By the time parade herald Inez Milholland reached the steps in front of the Treasury Department, the pageant would be coming to its glorious, dramatic finale, and the participants would stand in dignified silence as the rest of the 5,000 marchers proceeded down the parade route to Continental Hall. The pageant cast would join them there later and perform the final tableau again for the triumphant crowd.

No detail had been overlooked. Alice Paul made sure of it. This whole spectacle was her brainchild, and she had begun making plans and assigning tasks even before the National American Woman Suffrage Association had endorsed the idea or given her an official title. Now Paul was head of NAWSA’s congressional committee and chair of the parade committee.

She badgered Chief of Police Richard Sylvester into granting her a permit to use Pennsylvania Avenue. She lobbied the House Committee on the District of Columbia to pass a bill shutting down the streetcars between three and five o’clock. She used her connections in the Taft White House to make sure there was a cavalry unit standing by at Fort Myer, in case the D.C. police provided inadequate crowd control (although Chief Sylvester assured her that wouldn’t be necessary). And she negotiated with the inaugural committee to use the grandstand constructed at Fourteenth Street so distinguished guests could watch the pageant, then enjoy the parade.

Her public relations machine was relentless, making sure the march had been in the news so often and so thoroughly that it was almost considered one of the formal celebrations of Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration. Paul fed pithy quips to reporters wanting responses to the antics of the anti-suffrage crowd.

She held daily, sometimes hourly, rallies and fundraisers. She kept track of dozens of special train cars that carried hundreds of suffragists to Washington, each of whom needed a place to stay and wanted special attention. She arranged for local Boy Scouts to line the parade route. She encouraged women’s clubs to sell sandwiches and scalloped oysters to the spectators. One planning volunteer remarked that she had worked with Paul for three months before she found time to take her hat off.

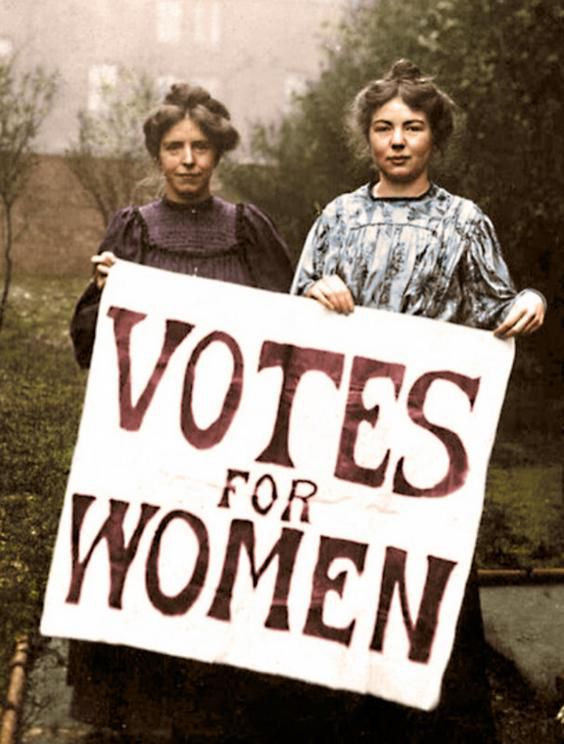

Christabel Pankhurst, daughter of Emmeline with Annie Kenne, another Suffragette

Then there were the details of the parade itself. Burleson and her attendants, both on horseback and on foot, would lead. Next came the striking figure of Milholland, Excerpted from the introduction of routinely described as “the most beautiful suffragist,” in flowing white robes and a golden crown atop a white horse. Behind he followed a wagon with a massive sign called the Great Demand Banner. It read: “We demand an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of this country.” No fewer than seven sections of marchers trailed behind it.

Representatives of the few nations with full suffrage — New Zealand, Australia, Finland, Norway — each designed a float ridden by costumed participants. Those countries where women enjoyed partial suffrage also sent marchers, who donned costumes and carried banners. A series of floats portrayed the changing status of American women since the suffrage movement began in the 1840s. Professional women, in matching thematic dress, were organized by occupation; the writers’ group had purposefully stained their costumes with ink.

The states where women could vote each sent a delegation, including members of Congress — who had to sneak past the sergeant at arms to participate, since Congress was in session. There were golden chariots… women’s marching bands… college women grouped by alma mater … a massive reproduction of the Liberty Bell. “General” Rosalie Jones and her army of pilgrims had hiked all the way from New York. Everything was designed to be visually striking for the live show and to look splendid in photographs.

Excerpted from the introduction of “Suffragists in Washington, DC: The 1913 Parade and the Fight for the Vote”byRebecca Roberts, a writer in Washington, D.C.