Enduring Lives, Persistent Memory

By • June 2, 2019 0 492

People die. That’s a fact.

But trailing behind like a thick cape is another fact. It is the fact that memory rears its high-minded head: the memory of the life lived, the things achieved, the contact made, the lives changed. If it is a fact that people die — and it is — then it’s also a fact that people remember and are remembered.

Memory is a factor of fame, a memory by any other name, whether it’s a memory remembered by millions or the immediate family, whether its resurrected and re-recorded, or lies still in someone’s dream. Such fame is rewarded with tributes or merely leaves a spot of emptiness that is duly and painfully noted.

So, here in these notes and notations, we remember the passing and the lives of a few of noted and famous men and women of achievement, different in size and importance whom we lost this May. We recall the legacy of words and books, as history or fiction. We recall the power of cinema and movies, the culture of American sports and a time-stood-still moment. We recall the solid achievement, done durably, of making government work, of music and songs and how some people danced. We recall the sound of laughter, of one or a thousand hands clapping.

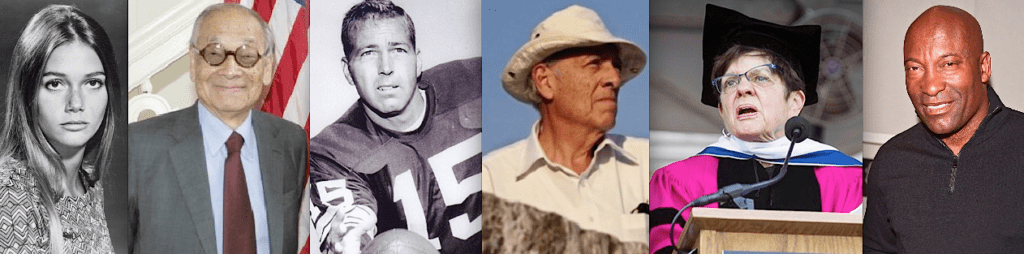

So, let us enter the stream of American sports, and of Bart Starr, who died in Birmingham, Alabama, at age 85 on May 26.

At various times late in his life, according to reports, Starr owned car dealerships, worked in real estate, and supported a charity for at-risk teenagers called Rawhide Boys Ranch. He was married for 60 years, the kind of example of the steadfastness of love, that is often cited but rarely happens.

But to football fans, to the rest of America, he was Bart Starr, also a measure of durability, in the 1960s a star quarterback in college (at Alabama) and for the Vince Lombardi-coached Green Bay Packers around which there lingers the quality of legend of the kind that is stronger than remembering the name of your first born.

Starr had statistics and trophies (six NFL titles among them) every bit as good as Tom Brady of the New England Patriots, but Starr’s football imagery rests in a singular moment, as it often does in sports. His fame rests on a remarkable career achievement as a football player, to be sure, but it contains the freeze-frame moment of New Year’s Eve day, 1967. It occurred with 16 seconds left in 13-degree below zero weather in Lambeau Field in Wisconsin. His team was behind 17-14 against the Dallas Cowboys. With 16 seconds left, Starr, Coach Vince Lombardi or somebody decided to keep the ball and run. Hordes of people saw it in the stadium, and millions of others and myself saw it on national television. Starr seemed to tumble, or squeeze or miraculously appear in the end zone, and it was one of those moments that only sports, with its rabid, unreasonable, memories-like-elephants fans, can produce: a frozen moment in the frozen landscape which won the game.

It’s certain that his friends, his family, his teammates and those he loved and loved him will remember him fully in his whole life, but Starr’s enduring fame is locked into that 16-second time frame pretty much forever, which is the way of fame in America’s world sports.

You can find fame endure in a life-time worth of architectural drawings, but the true reminder of the reminder of what I.M Pei left behind to most in Washington, D.C., is the East Building of the National Gallery of Art, a smooth, sharp-lined, construction which says modern art better than a thousand art reviews, and which both married (structurally and in terms of vision) the NGA’s more classic and historic West Building to art’s future in the East. Pei died at the age of 102 on May 16.

Alice Rivlin, who died May 14, left behind a resume of expertise, achievement, intellectual guidance on matters of economics and governmental that by itself casts a huge shadow. She exemplified the ideal of governing and of public service.

Rivlin also helped guide the District of Columbia through some of its most difficult times. Of her, Mayor Muriel Bowser: “As chair of the District’s federal control board, Alice not only helped guide our city back on a path to success, but also championed District home rule.” Rivlin was also vice chair of the Federal Reserve and director of the White House Office of Management and Budget. She was a pathfinder, a pioneer — the list goes on almost endlessly, like a sales receipt from CVS.

Tim Conway’s performance life was spent on television and a little more in movies. Think “The Carol Burnett Show,” especially, but also “Dorf,” “McHale’s Navy” and characters of singularity and a face out of which spilled a kind of endearing silliness, which is one of the great powers of comic performers. It’s not a stretch to compare him to silent movie clowns, whose personae were wars between grace and clumsiness. HE made us laugh. More importantly, he made his fellow performers laugh, often just by breaking up. Conway died May 14 at age 85.

And how about books as memory? If Herman Wouk, who died recently at the age of 103, is justly famous for his fictional takes on his own Jewish American background and on World War II, Edmund Morris, who died May 24 at the age of 78 of a stroke, was an ambitious biographer who, according to a Washington Post headline, “blurred line between fact, fiction with Reagan.”

That was a reference to his gutsy, strangely-structured but haunting biography, “Dutch,” of President Ronald Reagan, which is a work that would still have the power to stir debate. But his three-part biography of Theodore Roosevelt — “The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt,” “Theodore Rex” and “Colonel Roosevelt” comprise a monumental and readable achievement, right up there with David McCullough’s “Truman.”

The African American film director John Singleton had a rich film career, but it began at the top: his first film, straight out of film school, was “Boyz in the Hood,” a critically acclaimed, financially successful hit about black street life in Los Angeles, which included Oscar nominations for Singleton in best direction and original screenplay at the age of 24. He died April 28 of a stroke at the age of 51.

Singleton never matched anything like “Boyz” in terms of prestige. It was considered Spike Lee territory, gritty, tough, realism with star power that included young actors like Cuba Gooding Jr, the remarkable Angela Bassett (see the current “911” on Fox and her great turn in “What’s Love Got To Do With It” as Tina Turner) and the always intense Laurence Fishburne. Singleton had other successes, including music videos with Michael Jackson and popular hits like “Shaft” and “Fast 2 Furious,” but it was the boys which give him the legacy of permanence.

Actors and actresses are chameleons, especially but not exclusively on film—just look at what Glenda Jackson is doing today on Broadway as “King Lear.”

There was a time — a brief one — when Peggy Lipton and her co-stars Clarence Williams III and Tige Andrews of the street-cool cop show, “The Mod Squad,” where the epitome of cool, especially Lipton with her willowy, long haired and not touchable good looks. She seemed to be the last flower girl, but with a gun.

Lipton also appeared in “Twin Peaks” and a recent return to that David Lynch wobbly weirdness. She recorded two songs by Laura Nyro, not surprisingly perhaps, including “Stoney End” and “Lu,” married pop-soul-rock impresario Quincy Jones and most recently appeared on the quirky “Angie Tribeca” series. She died May 11 at the age 72 of colon cancer, with daughters and fellow actresses Kidada and Rashida Jones at her side.

Lipton, on screen and in the public eye, like the South African actress Genevieve Waite, who died recently at the age of 71, seem just a little out of reach, with careers and lives built on unforgettable pieces of here and there. Waite was in “Myra Breckenridge” and the David Bowie star vehicle, “The Man who Fell to Earth,” and cut an album called “Romance is on the Rise,” produced by her ex-husband John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas.