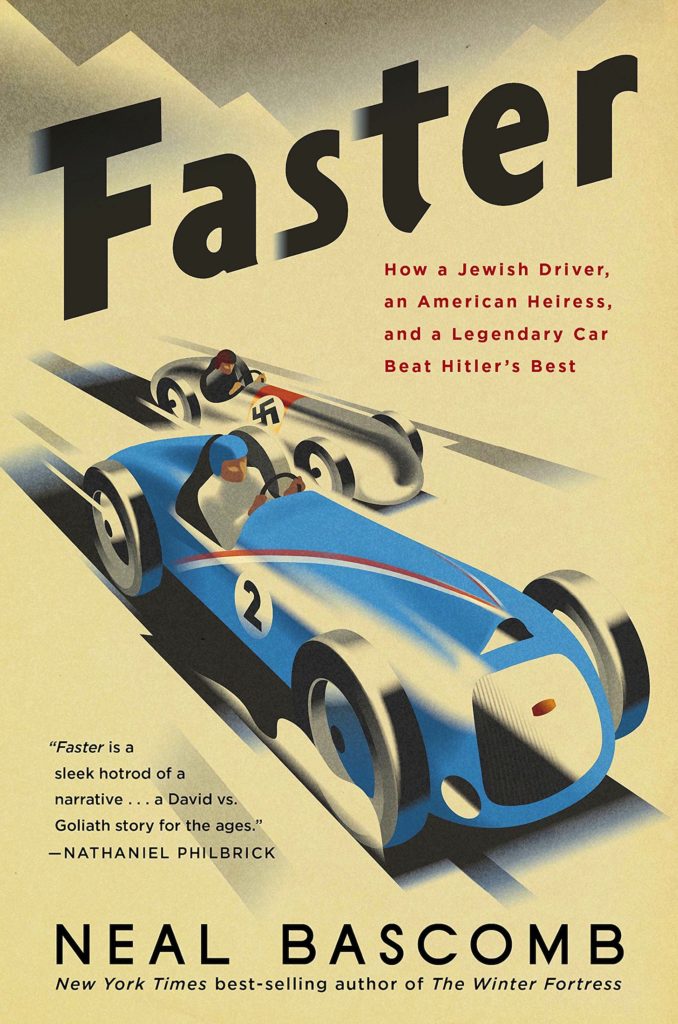

‘Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler’s Best’

By • April 8, 2020 0 2232

By Kitty Kelley

This accounting of an iconic 1938 race recaps every twist and turn, for better or worse.

Racing in the European Grand Prix is like playing at Carnegie Hall, singing at the Met or scaling Mount Everest. It is the epitome of excellence — achieved by few, but thrilling thousands. Enzo Ferrari called it “this life of fearful joys.”

In 1938, the Grand Prix involved something more than two race car drivers pitting themselves and their countries’ fastest automobiles against each other in a 100-lap race for superiority. In that particular year, the Grand Prix came down to: Dreyfus versus Caracciola, Delahaye versus Mercedes, France versus Germany, Good versus Evil.

In his newest book, “Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler’s Best,” Neal Bascomb documents every detail of the contest between René Dreyfus, an American-financed French Jew driving a Delahaye 145, and Rudi Caracciola, representing Germany in a Mercedes Silver Arrow. It was a titanic struggle between two nations that would lead one to humiliating defeat and the other to resounding victory.

Bascomb begins the story in 1933, when Adolf Hitler becomes chancellor of Germany and, as leader of the Third Reich, makes a major speech promoting Germany’s automobile industry, which he pronounces his “beloved child.” Hitler’s Silver Arrows and their blond, blue-eyed drivers stood for more than sporting prowess.

“They represented the master race conquering the rest of the world,” Bascomb writes, showing that Daimler-Benz wasted no time ingratiating itself with the Führer by immediately increasing production of military trucks, armored vehicles, aircraft frames and tanks. Soon, Nazi propaganda trumpeted, “A Mercedes-Benz victory is a German victory.”

Within five years, Germany had annexed Austria. In March of 1938, a month before the Grand Prix, Caracciola, Germany’s premier race car driver, issued a public proclamation endorsing Hitler’s policies and supporting the Anschluss:

“We racing drivers are fighters for the world-class German automobile industry. Our victories are at the same time triumphs of German engineering and workmanship. The Führer has once again given our factories the opportunity to build racing cars … their unique successes over the past four years represent a glorious symbol of the efforts of our leader.”

The glamour attached to the 1938 Grand Prix drew worldwide attention, and victory seemed assured for Germany as Dreyfus, unlike Caracciola, did not have a world-rated record of wins. In addition, the Delahaye 145 seemed like a plodding mule next to Daimler-Benz’s sleek thoroughbred.

But Dreyfus had the financial backing of American Lucy O’Reilly Schell, a rally driver herself. The only child of wealthy parents and “decidedly nouveau riche and unapologetic about it,” she inherited millions from her father’s fortunes in construction, factories and real estate, and married a man who didn’t work. So she financed their shared passion for racing.

The wealth of detail in this book will rivet automobile enthusiasts; others might want to take a pass. For example, “The prototype Mercedes engine, a supercharged 3.3 liter straight-eight … was … not a revolutionary design, [but] it benefited from ultraprecise construction and a host of improvements, allowing for horsepower measurements 50 percent greater than the Alfa P3.”

Those familiar with race routes will recognize the locales in which Bascomb chases every hairpin turn, every straight and every rise and fall: La Turbie outside Nice, the Nürburgring in the Eifel Mountains, Montlhéry, south of Paris, the streets of Monte Carlo in Monaco and Pau, on the edge of the Pyrenees between Spain and France.

The author whirls readers around curves, bullets down hills and twists ulcer-making bends, with death beckoning at 250 mph. “Grand Prix racing was like all motor car racing,” Bascomb writes, “balanced on the very brink of death.”

Documenting the 100 laps of the 1938 Grand Prix demands much from a writer whose verbs must ricochet off the page like rocketing electrons: zoom, careen, brake, zigzag, swoop, streak, charge — faster and faster and faster — until victory is finally achieved.

Only then does the Frenchman step out of his Delahaye 145 in front of Hitler as the band strikes up “Le Marseillaise” to celebrate France’s triumph over Germany. René Dreyfus was to the French what Babe Ruth was to Americans: a bona-fide hero — which gives Neal Bascomb’s eighth book a Cinderella ending and a surefire film adaptation.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.”