Convention-Unlike-Any-Other Has Some Good Points

By • August 20, 2020 0 779

The 2020 nominating conventions for the Democratic Party, taking place this week, Aug. 17 to 20, and for the Republican Party, taking place next week, Aug. 24 to 27, are unlike any of the past, at least in one significant way. The tens of thousands of elected delegates, state party leaders, stars and members of the press, all credentialed to attend the four-day events in person, are instead meeting, voting, speechifying and reporting remotely.

Reactions to the change have been mixed.

The roll call vote of states, territories and D.C. — featuring often touching stories by a broad swath of American citizens in their homes and places of business and at local landmarks — seems to have been a hit. Media pundits across the political spectrum have remarked that the on-site reps were more refreshing and relevant than credentialed delegates in a large convention hall.

But some of the speeches, taped, it seemed, days ahead, had a disjointed feel. On the first night of the convention, Michelle Obama, the nation’s first African American first lady, did not mention the historic nomination of multi-ethnic Kamala Harris as vice president. Also disconcerting: when Harris spoke the stirring words, “I accept the Democratic nomination for vice president,” on Wednesday night, her statement was greeted by utter silence.

A political party’s quadrennial nominating convention used to be the Super Bowl for party stalwarts, according to Charles Wilson, head of D.C.’s Democratic delegation. “The voting and politicking always took place in an atmosphere of great anticipation, participation and excitement,” he said. So did the many dinners, receptions and parties, where legislators and activists met, lobbied and networked. In fact, for almost everyone who got credentials, the personal networking was the point of the convention (and, for many, an important career event). That is changed.

Not the First Change to Conventions

It’s not the first big change to the conventions, which have met since the 1830s. In fact, the essential reason for the nominating conventions — to have party activists gather together to select the presidential candidate — hasn’t happened since the 1970s. The violence of the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago changed that.

At that convention, the Democratic party was divided, as now, among strong factions, from George Wallace on the far right to Eugene McCarthy on the far left. The delegates eventually nominated the amiable moderate Hubert Humphrey, as tear gas from antiwar and antiracism riots outside seeped into Chicago’s International Amphitheatre (for the record, Richard Nixon won the election, replacing President Lyndon Johnson, who had ushered in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Great Society programs of 1965).

After that disastrous convention, both parties focused on primaries and caucuses to choose their candidates, who would be officially anointed at conventions in late summer. The conventions themselves became a way to energize party members to support the candidates, get out the vote and produce party platforms that addressed the issues that were top-of-mind for various interest groups.

What Is Still the Same

For the next 50 years, nomination conventions revolved around remarks by keynote speakers, culminating with the vice-presidential and presidential candidates’ acceptance speeches, which took place live after 6 p.m. Pacific Standard Time (9 p.m. Eastern) and lasted two hours. Both parties had similar evening formats with similar hoopla.

But each political party organized its daytime events for conventioneers differently. Republicans usually met during the day in state and regional delegations and around certain issues and party and think-tank leaders. Democrats, however, organized their convention afternoons around meetings of caucuses and councils representing various identity groups such as women, Blacks, Latinos and gays and lesbians. Each caucus usually focused on a single issue or two and treated each group as monolithic. In 2012, Obama senior advisor Valerie Jarrett literally ran from caucus to caucus, speaking about immigration to the Latinos, abortion to the women, racism to the Blacks.

During this year of virtual conventions, these groups still are meeting, though remotely, at designated two-hour periods each day. While the panels are made up of representatives of many of the same groups, each focused on a narrow range of issues, the videotaped sessions are more accessible to those interested, but without provision for interaction.

What hasn’t changed is that conventions, live or remote, mainly talk to their choirs.

For the Democrats so far, the chief priority, the energy and the speeches have all been about getting out the Democratic vote to defeat (the nice word) President Donald Trump. There is not one keynote speaker but 17, the Democrats proclaim. All have touted the same message: that the country and democracy itself has been ruined by the Republican president and that only the Democrats can save it. Everything is Trump’s fault. Even former President Barack Obama’s speech on Wednesday evening was critiqued by many pundits as being gloomy, lacking his usual charm and self-deprecating humor.

While all the Democrats have in one way or another promised to end racism in America, there has been little focus on specific solutions to challenges. On Wednesday night, there was some video dialogue about gun control, immigration, etc. But there was no mention of the increasing violence and number of homicides in U.S. cities, including Washington, D.C., nor of the challenge of creating enough jobs for unemployed Americans as well as for increasing numbers of immigrants. And no well-thought-out path was offered for opening schools, even as Elizabeth Warren spoke from a closed child care center (displaying BLM in reference to the Black Lives Matter movement).

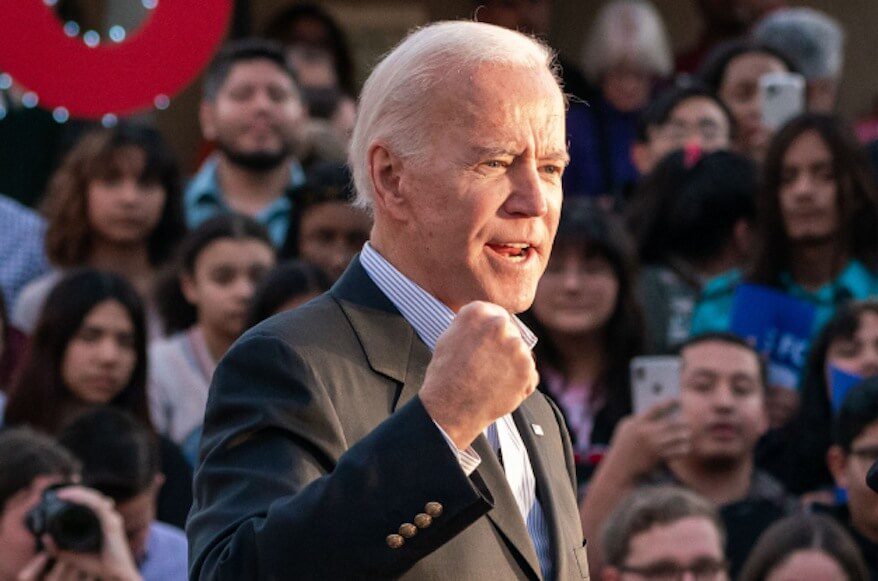

Democrats everywhere say they hope and expect Joe Biden to be more uplifting and plan-oriented in his nomination acceptance speech tonight, Aug. 20, around 10:40 p.m. Eastern. They want some spark, some fun. It’s okay if it’s virtual. Many people have told The Georgetowner that what they like most about the remote convention is seeing more “real” people in their own homes.

If only it would help to yell at the screen, “No more talking heads!”