Beautiful Things at the Phillips Collection

By • November 12, 2020 0 1476

Any other year, this would have been a perfect fall arts season. 2020 has not been kind, but it gave Washington an undeniably gorgeous fall. It was the kind of weather made for walking through Georgetown on a Friday-night gallery walk. It would have been a season for strolling in and out of museums on Sunday afternoons, for lingering outside after an evening art lecture, chatting with new friends as dusk fades into night.

But this year is different. Frankly, art has not been on my mind much over the past month. This is an art column with the backdrop of a pandemic and in the wake of an unbelievably violent presidential election. There have been more demanding issues to address.

Still, despite tremendous obstacles, many museums in Washington have reopened. They are all practicing impressive safety measures: timed ticketed entry, temperature checks upon arrival, socially distanced gallery navigation and incredibly helpful and gracious museum guards. I have not yet returned to a restaurant or cut my hair since the beginning of the pandemic, but museums I cannot keep away from.

Now, as always, there is beauty on the walls of the Phillips Collection.

Ascending to the second floor, you are met with Renoir, Courbet and Cézanne. I was drawn immediately into a small Cézanne, “Fields at Bellevue.” I inspected everything, from the bluish-yellow shadow of a distant cottage to the creamy, lopsided, unfinished edge of the canvas to the wormy, washed-out wood of the chunky acanthus-leaf frame. It was like seeing a painting for the first time.

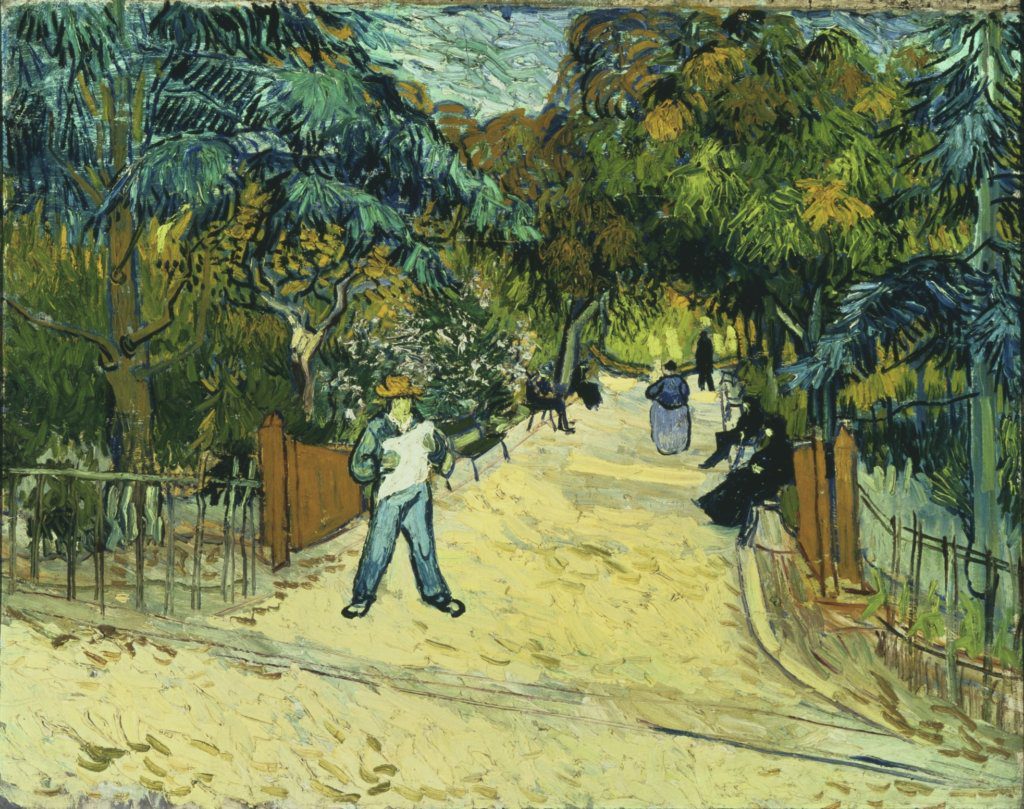

I watched my wife gaze spellbound into van Gogh’s “Entrance to the Public Gardens in Arles.” She was fixated for an endless moment on a tapestry of foliage in the upper left corner of the canvas. When I asked her what she was looking at, she said, “The paint is just so thick. I forgot how thick paint is.”

There was Stuart Davis and Piet Mondrian, playing their weird midcentury jazz-on-canvas riffs, both with razor-clean edges, hard lines and flat colors that still somehow insist on being lush and painterly, aggressively handmade. There’s a bizarre little Georges Braque, “The Shower,” which is so un-Braque-like that I’m not sure it wasn’t mislabeled, but I loved the curiosity of it.

There was McArthur Binion’s “DNA: Black Painting: 1,” a quilt-like painting that touches on the oppression of birth itself and the inescapability of racial heritage in America. There is Phillip Guston’s “Native’s Return,” with a brusque, disheveled, hatching quality that somehow compliments the Binion. It also reminded me of Rembrandt the way the focus of the painting lumps toward the center of the canvas as if by gravity, with the edges dissolving into wash. The painting could easily be titled “Rembrandt’s Nose.”

There is also an impressive handful of exhibitions on view. “Hopper in Paris” is a selection of early works by Edward Hopper, from when he traveled to Paris shortly after finishing his training at the New York School of Art. Years ago, I read a critique that Hopper’s early Paris works were not very good — that he wanted to be an Impressionist but it didn’t square with his particularly American sensibility. I still think that’s true. But it’s interesting to see a series of early and decidedly non-masterpieces by a future giant.

“Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition” — one hell of a strong exhibition and a nice surprise — explores the connections between European modernism and African American artists of the 20th and 21st centuries, featuring artists such as Romare Bearden, Bob Thompson, Elizabeth Catlett, Hale Woodruff, Beauford Delaney and Carrie Mae Weems in dialogue with Kandinsky, Matisse, Manet and Picasso.

In the early part of the century, African American artists contributed to modernism’s new languages of form and color, and its complex engagement with the arts of Africa. But in later years, artists began challenging master narratives, using humor and satire to question the supposed superiority of European art.

One critique here is the way the exhibition funnels European modernism from Manet to Picasso through a single apparatus, which is untenable simply in how drastically different these connections become after Western artists are introduced to native African art in the first decade of the 20th century. Still, it’s a wonderful show that deserves to be seen and discussed.

Museums have done commendable work throughout the pandemic, making their collections available online through their websites and social media. But there is only so much you can see through a screen. Going to a museum right now and engaging with the depth and dimensionality of real-life art is a vital escape into beauty.

The Phillips Collection, 1600 21st St. NW

Thursday to Sunday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Timed-entry tickets released at noon on Monday.