THIS OTHERWISE INFORMATIVE HISTORY IS HAMSTRUNG BY ITS FIXATION ON SYLVIA PLATH’S NOTORIOUS SUICIDE

Back in the day (circa 1930 – 1960), small-town girls with big-city dreams headed for New York and checked into the Barbizon Hotel for Women at 63rd and Lexington. Upon arrival, they were greeted by doorman Oscar Beck, welcomed by Connor, the hotel manager, and scrutinized by the front desk matron, Mrs. Sibley, who allotted the best of the sliver-sized rooms to “the Daisy Chain,” those who attended one of the Seven Sisters: Barnard, Smith, Mount Holyoke, Vassar, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley, and Radcliffe. Everyone else had to provide social references and three letters of recommendation.

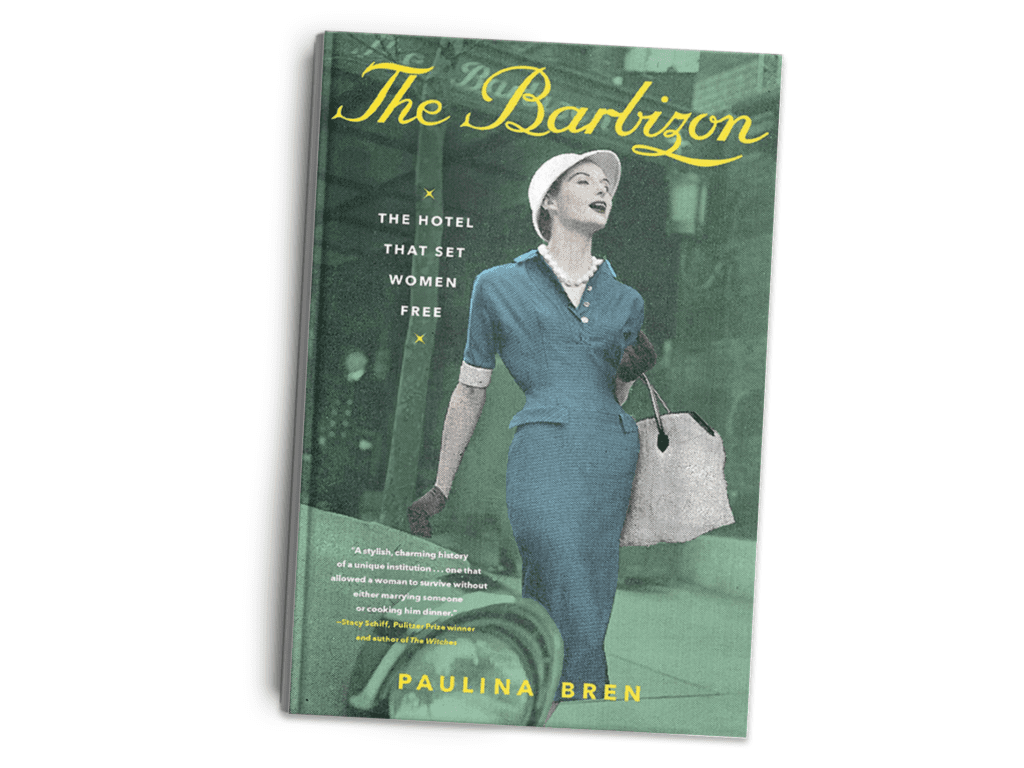

As Paulina Bren writes in The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free: “In the national imagination it was understood that the East Coast was the country’s intellectual hub while the rest of the country remained its backwater.”

During the era of white gloves, pillbox hats, and hose and high heels, the Barbizon (rhymes with bygone) offered 22 floors of “gracious living” in “utmost security” (no men allowed above the lobby), plus a rooftop garden terrace, a swimming pool, artists’ studios, a coffee shop, formal dining room, solarium, library, and the Corot Room for Thursday teas, complete with a pianist.

From 1927 to 2005, the Barbizon was the ne plus ultra for young women seeking careers as artists, writers, dancers, singers, and actresses. For those without such talents, there was the Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School, which reserved several floors at the hotel with imposed curfews, house mothers, and skirt police who barred wearing slacks in public.

Mademoiselle magazine also reserved Barbizon rooms for their “Millies,” as guest editors were called. These competitively selected coeds (15 – 20) from colleges around the country arrived every June for glamorous month-long internships to produce the magazine’s August back-to-school issue. The modeling agencies of John Powers and Eileen Ford booked several floors of the hotel for their aspirants, as did the Parsons School of Design, the Tobe-Coburn School of Fashion Careers, and the Junior League.

Over the years, the Barbizon burnished its image as a dormitory for debutantes. During World War II, when General “Wild Bill” Donovan put out a call for women to come to work for the Office of Strategic Services, precursor to the CIA, he said his ideal would be “a cross between a Smith College graduate, a Powers model, and a Katie Gibbs secretary.”

The list of Barbizon alumnae includes Grace Kelly, Gene Tierney, Lauren Bacall, Joan Didion, Ali MacGraw, Tippi Hedren, Joan Crawford, Jaclyn Smith, Gael Greene, Nora Ephron, Ann Beattie, Betsey Johnson, Candice Bergen, Liza Minelli, Cybill Shepherd, Elaine Stritch, Cloris Leachman, and Molly Brown, the Titanic’s most famous survivor. Even Edith “Little Edie” Bouvier, star of the documentary “Grey Gardens” and the cousin of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, lived at the hotel from 1947 – 52, until she was called home by her mother, Big Edie, to take care of her and the cats.

The Barbizon has been featured in novels like Mary McCarthy’s The Group, The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe, Searching for Grace Kelly by Michael Callahan, and, most famously, The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, a 1953 “Millie” who used the experience to write her only novel. Authors Jacqueline Susann, Jackie Collins, and Judith Krantz followed suit by placing characters in women-only residences like the Barbizon — now a condominium listed in the National Register of Historic Places and designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Given its history and colorful residents, the Barbizon deserves bookshelf space alongside other high-profile-building biographies: Life at the Dakota: New York’s Most Unusual Address by Stephen Birmingham; 1185 Park Avenue by Anne Roiphe; House of Outrageous Fortune: Fifteen Central Park West, The World’s Most Powerful Address by Michael Gross; and The Plaza: The Secret Life of America’s Most Famous Hotel by Julie Satow.

As a Vassar College professor of gender and media studies, Bren brings impressive academic credentials to her history of the Barbizon. Unfortunately, her book’s subject, at least in her telling, does not live up to its billing as “the hotel that set women free.”

Rather, the Barbizon that Bren presents seems to have been primarily a secure waystation for young women who wanted to experience living in Manhattan before they got married. According to (and reiterated endlessly by) the author, marriage was always the end goal: the brass ring on life’s merry-go-round. Anyone residing at the Barbizon past her sell-by date of four years without a marriage proposal was headed for a lifetime of misery (i.e., spinsterhood).

“As bold as one might be, however big one might dream, as a young woman you knew that the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow was marriage,” Bren writes. “[It] had to be marriage. Even if part of you longed to be actress, writer, a model or artist…[A]ll the women at the Barbizon shared the ultimate goal — marriage.”

Bren bangs that drum throughout, writing of the young women staying at the hotel: “Their time at the Barbizon [was] a short window of opportunity that would usher them toward the ultimate goal of marriage.” To the regrettable exclusion of the hotel’s dozens of other notable residents, the author seems transfixed by the morbid memory of Plath, who committed suicide in 1963 at the age of 30, while separated from her husband. “It was her final, successful suicide attempt, with the first right after June 1953, and others most probably in between,” writes Bren. Readers might wonder if her editor was AWOL, searching for “others most probably in between,” because the author provides no documentation in her

text or chapter notes.

The threnody of Plath’s suicide haunts many of the chapters of this book, as The Bell Jar was an homage to the Barbizon, which Plath the novelist renamed the Amazon. As one of the “Millies” wrote after a 2003 reunion at the hotel: “Do you find it as unpleasant as I that the reunion would not have taken place had Sylvia not stuck her head in the oven?”

One could say the same about this book.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” kittykelleywriter.com