Ukraine vs. Russia: Key Historical Dimensions

By • January 31, 2022 3 2296

Signs of imminent Russian invasion of Ukraine have dominated news headlines in recent days. The deployment of close to 100,000 Russian troops into neighboring Belarus and along Ukraine’s borders combined with increasingly alarming diplomatic announcements from U.S. and NATO representatives – including the call to evacuate U.S. embassy personnel from Ukraine’s capital Kyiv – have many wondering if a major European war is imminent.

Unfortunately, in the west, much of the news analysis of the crisis has focused on short-term causes of tension between Russia and Ukraine rather than longer-term, deeper historical patterns in the region, much to the detriment of clear-eyed assessment.

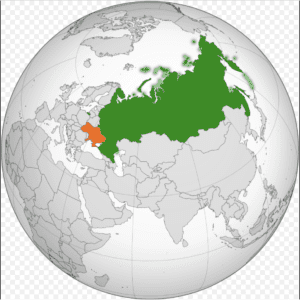

Ukraine (in Red) and Russia (in Green). Map image courtesy Wikipedia.

Questions such as the following have focused our attention: Is Putin simply trying to pressure NATO to forswear allowing Ukraine to join its defensive alliance – which has added member states closer to Russia’s borders since the fall of the Soviet Union? Will the threat of U.S. economic sanctions deter Russian invasion of Ukraine? Should the U.S. and its NATO allies speed delivery of defensive weaponry to Ukraine? Has the U.S. fallen short by not stepping up more quickly to defend a burgeoning European democracy threatened by Russian invasion?

The Embassy of Ukraine is located in Georgetown at 3350 M St NW. The house in which it resides was once owned by William Marbury of Marbury vs. Madison (1803) fame. Photo by Chris Jones.

But, a deeper historical understanding of the bitter and centuries-old background between the Ukrainian people and the Russian colossus to the east might help us better understand the nature of the regional crisis at hand.

For this, we need to look back in history. In doing so, we’ll see that Ukrainian national pride and Russian predation are consistent over time.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, Ukraine – then known as Kyivan Rus – was the “largest and most powerful state in Europe,” according to the CIA World Factbook. Following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, however, Kyivan Rus was absorbed by Lithuania and Poland while the Russian empire recovered and grew powerful to the east. Despite a sense of deep national identity and pride – which persists to this day – Ukraine was then absorbed into the Russian Empire by the mid-17th century.

By the early 19th century, the Russian Empire and its czars considered Ukrainians to be ethnically Russian, despite Ukrainian resistance. In 1804, Russia banned Ukrainian language instruction from schools. Ukrainian publications, performances, lectures and music were mostly banned in Russia in the 19th century.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, a Ukrainian war of independence from Bolshevik Russian rule was crushed during the Russian Civil War. By 1922, Soviet Ukraine became one of the first satellite states of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

The Holodomor

Then, the “Terror-Famine” was launched against Ukraine.

Under Stalin’s rule of the Soviet Union (1929-1953), Ukraine suffered the most traumatic chapter of its long history – the Holodomor – from 1932-33. In Ukrainian, “Holodomor” means “extermination by hunger.” Stalin’s policies of forced collectivization and the targeting of Ukrainian ethnic Kulaks – whom Stalin considered a counter-revolutionary class – required Ukrainians to ship essentially all farm produce to Moscow, resulting in man-made, mass famine estimated to have killed between 3.9 to 7.5 million Ukrainians and some 7 to 10 million people under Soviet domination.

Of course, estimates of the number of Ukrainians who died during the Holodomor vary widely – as one might predict given the disinformation associated with the superpower rivalry in the later Cold War era and up to today. Public sources such as Wikipedia provide Holodomor death totals ranging from a low count of 3.9 million Ukrainians (under the “Holodomar” listing) to as high as 7.5 million (under the listing of “Soviet Famine of 1932-33.”) In a Fact Sheet of January 20, 2022, the U.S. State Department recently embraced the figures of 7-10 million Holodomor deaths referencing research from the Europe vs Disinfo website (euvsdisinfo.eu.).

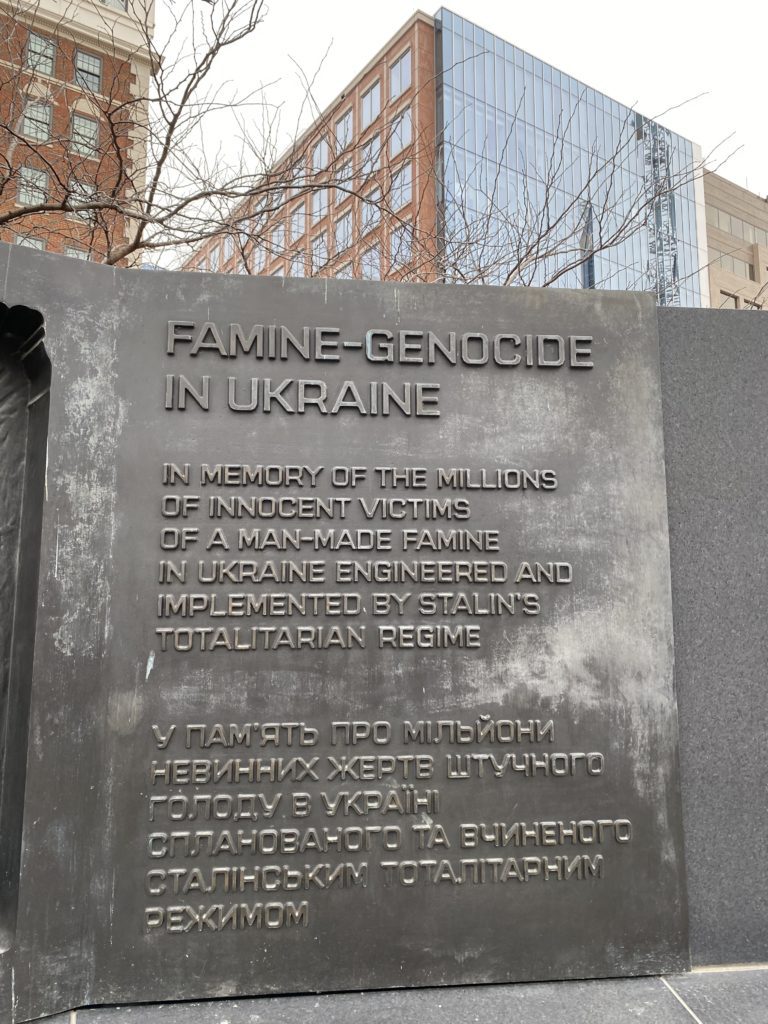

Though the Holodomar’s death statistics are always in contention in such public forums, Ukrainian officials hold Stalin and the Soviet Union responsible for launching a twentieth-century genocide against their people. In 2010, a Kyiv appellate court found Stalin and others “guilty of genocide against Ukrainians during the Holodomor famine,” according to a Radio Free Europe broadcast of January 14, 2010. Four years earlier, in 2006, the U.S. Congress had approved of The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932-33 in Washington D.C. Managed by the National Park Service, the memorial opened to the public at 1 Massachusetts Ave. NW on November 7, 2015.

The Holodomor Memorial to Victims of the Ukrainian Famine-Genocide of 1932–1933 is located at 1 Massachusetts Ave. NW and is operated by the U.S. National Park Service. Photo by Chris Jones.

Following the Nazi-Soviet Pact of August, 1939, Hitler of Germany and Stalin of the Soviet Union invaded Ukraine on their way to carving up Poland. While many Ukrainians welcomed liberation from Stalin’s terrorizing rule and cooperated with Nazi authorities, an underground “partisan movement” formed and a Ukrainian Insurgent Army rose to fight off both Soviet and Nazi occupation.

By 1945, with Soviet and Allied victory over Nazi Germany in the Second World War, much of Stalin’s anti-fascist propaganda remained focused on Ukraine. Following Soviet losses of over 20 million people in the Second World War, Russian communist bitterness over Ukrainian collaboration with Nazi occupation – either real or amplified – remained strong, as it does to this day.

Putin Continues Stalin’s Approach to Ukraine

Russia’s current president, Vladimir Putin, continues to characterize Ukraine’s history and independent cultural identity much as Stalin did. Born in Leningrad in 1952, the last year of Stalin’s life, Putin came to admire the Soviet Union’s deadliest totalitarian dictator (with Stalin’s death statistics often starting as high as 20 million and moving to as high as 60 million.)

While studying law at Leningrad State University in the 1970s, Putin joined the Communist Party and by 1975 began to serve in the KGB, becoming an officer and later serving in East Germany. Putin admits today that he believes Soviet domination of eastern Europe under Stalin’s rule served as a high point in Russian history while the loss of Russia’s satellite states in eastern Europe following the Cold War was a geo-strategic “disaster.” Following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union Ukrainian officials agreed to relinquish their nuclear arsenal in exchange for Russian assurances to not invade Ukraine.

In 2014, during the Obama administration, Americans were shocked when Russian forces annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and took control of the strategic Black Sea ports long sought by Russia. Putin justified the seizure as an historical “return” of Russian-speaking Crimeans to the Russian Federation. According to Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center writing in The Washington Post, Russian propaganda described the 2014 annexation of Crimea as a “liberation” of Ukrainian and Belarusian lands” with “both Stalin’s USSR and Putin’s Russia” coming to “help their brethren” historically. With Putin’s public embracing of Stalin’s legacy, a 2019 poll of Russian attitudes revealed that Stalin scored a 70 percent approval rating for his leadership of the Soviet Union, according to Kolesnikov.

“…You have to understand that Ukraine is not even a country. Part of its territory is in Eastern Europe and the greater part was given to us,” Putin told U.S. president George W. Bush at the NATO summit in Bucharest Romania in April 2008, according to former National Security Council staff expert on Russian and Eurasian affairs, Fiona Hill, as reported in The New York Times.

Following Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, Putin fomented an internal “separatist movement” in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine as a pretext for sending Russian forces into Ukraine to “protect” the Russian-speaking western Ukrainians. Known as Putin’s “little green men,” these invading Russian troops wore no insignia in battle, so their affiliation with Russia was easily denied. Today, Russian military personnel continue to support the “separatists” occupying the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine.

Armed men without insignia (so-called “little green men”) at Simferopol Airport, 28 February 2014. Photo and caption courtesy Wikipedia.

In addition to annexation and invasion of Ukrainian territory, Russia’s president Putin has also sanctioned cyber attacks against Ukrainian soft targets, shut off key gas pipelines in Ukraine during the winter, and used internal Ukrainian political battles over Russian-backed Ukrainian politicians as a pretext to interfere with U.S. domestic politics. Russian disinformation campaigns after the 2016 U.S. presidential elections sought to shift attention to Ukrainian “interference” in favor of Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton rather than Russian interference in favor of Republican candidate Donald Trump. Additionally, the first impeachment of President Trump in January 2020 involved the president’s questionable phone call to Ukraine’s pro-western president Volodymyr Zelensky to discuss a possible quid pro quo of defensive weaponry in exchange for damaging information against the Bidens.

Today, as Russian forces surround Ukraine for a possible all-out invasion and seizure of its capital Kyiv, it bears keeping in mind Ukraine’s long national independence struggle and its enduring cultural identity and achievements. We should also remember what Ukrainians will never forget – Russia’s history of genocide against the Ukrainian peoples, its relentless stream of disinformation, its continuing diplomatic and military hostility, and its brazen designs to reabsorb Ukraine and other eastern bloc “republics” back into the Russian motherland.

Thank you for publishing this excellent synthesis of the Ukrainian/Russian history. In order to make decisions in the present we must understand the past.

Thank you so much! Agree wholeheartedly. Let’s hope the decision makers act wisely…

As a Ukrainian-American I am pleased that your article has so well described the Ukrainian plight. So few know the really history of Ukraine. Today’s unfortunate situation in Ukraine has enlightened people about the truth of Ukraine’s relationship with Russia over the years.