Last Chance: Jasper Johns in Philly

By • February 3, 2022 0 2168

“Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror,” the two-museum, two-city retrospective of work by the 91-year-old artist many consider the greatest living American painter, closes on Sunday, Feb. 13. You may feel all Johnsed out after seeing the Whitney Museum of American Art’s full-floor show, but don’t quit. The roughly chronological installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art might just be this landmark exhibition’s better half.

The curators—Scott Rothkopf at the Whitney and Carlos Basualdo at the PMA—divvied up the Johnsian trove in line with the exhibition’s yin-yang theme. For starters, each show includes one of the two editions of the paired, painted bronze Ballantine cans that flabbergasted the art world in 1960.

And each has its share of classic abstracted targets, sagging string “catenary” paintings (from the late 1990s) and Neo-Dada canvases such as, in Philadelphia, “Fool’s House” of 1961-62. On this splotchy gray, what-to-make-of-it work, a broom and a white cup hang from hooks, with the words “Broom” and “Cup”—and “Towel” and “Stretcher,” pointing to other attachments—painted in cursive with helpful directional arrows.

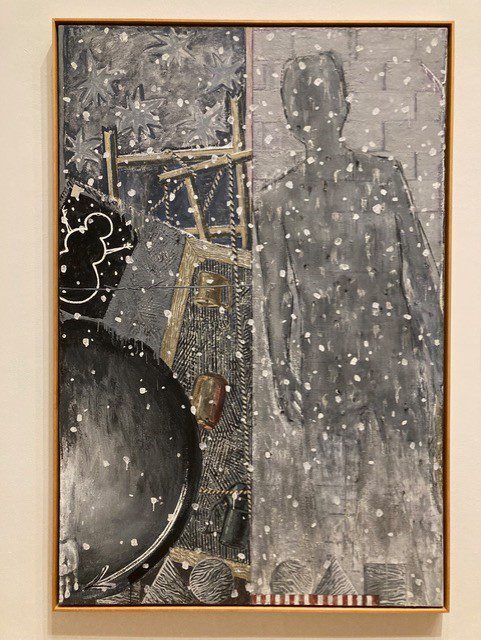

Johns’s mid-1980s matched foursome of paintings, “The Seasons,” was split up, with New York getting “Fall” and “Spring” and Philadelphia getting “Winter” and “Summer.”

Jasper Johns’s “Winter.” Photo by Richard Selden.

In New York, a large gallery is devoted to the proto-Pop Artist’s encaustic paintings of 48-star U.S. flags over collaged newspaper and brightly colored, semi-deranged North American maps; Philadelphia, by way of contrast, plays up Johns’s obsession with numerals (although the PMA show opens with the Museum of Modern Art’s “Flag” of 1954-55 and perhaps the most striking gallery at the Whitney displays numeric grids, cast in metal and bathed in natural light from Hudson-facing windows).

Intriguingly, each museum has partially recreated a significant Leo Castelli Gallery exhibition. At the Whitney, we see work from a 1968 show. The PMA has stunningly rehung six oddly compartmentalized paintings of the eight shown at Castelli in 1960, four with bursts of red, orange, yellow, blue, gray, and white—sometimes with the misplaced stenciled names of the colors—and two similar works in black, white and gray.

These allotments seem fair and balanced, but in one case Philadelphia surely got the better deal. The Whitney gallery that focuses on a place (other than New York) influential in Johns’s career displays work from Edisto Beach, South Carolina. What locale did the PMA claim? Japan.

Johns’s first encounter with Japan was six months of army service in Sendai in 1955-56. In 1964, he spent several months working in Tokyo, also visiting Osaka’s avant-garde Gutai Art Association. Two years later, he returned for the opening of the National Museum of Modern Art’s “Two Decades of American Painting” exhibition, which featured four paintings by Johns.

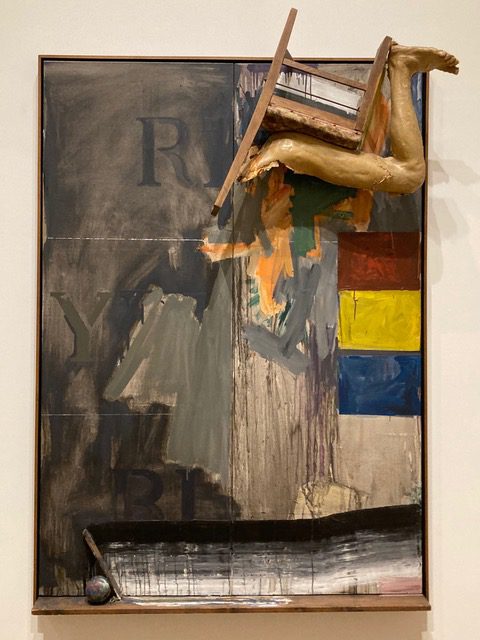

“Watchman,” the first painting he made in Japan, in 1964, is on view in Philadelphia. The title of this large, vertical work, which powerfully combines some of his signature Pop/Conceptual elements and themes, refers to a somewhat obscure distinction Johns latched onto between the “watchman” and the “spy.”

Jasper Johns’s “Watchman.” Photo by Richard Selden.

Mostly painted in grays, with wide slashing strokes that are allowed to drip, the canvas has bars of red, yellow and blue stacked like a flag at right and irregular patches of orange and green at center. The stenciled words RED YELLOW BLUE that appear in other Johns works are nearly obscured at left. At the bottom, a steel ball on a platform blocks a tilted board that appears to have smeared paint—white at bottom then gray then black—squeegee-like from right to left. Most obtrusive, a wax cast of a man’s leg “sits” in half of an upside-down chair affixed at upper right, extending from and above the canvas as if in mid-tumble.

The show’s Japan section includes both works by Johns and by Japanese artists with whom he interacted; “Happy New Year,” a set of miniature artworks by each of the 29 Gutai artists, given to Johns in 1967; sketchbook pages and documents from his Japan visits; and a 35-minute interview film by Katy Martin documenting Johns’s work between 1978 and 1981 with Hiroshi Kawanishi and other printmakers at the Simca Print Artists studio, which moved from Tokyo to New York in 1971.

Another product of Japan’s decisive impact on Johns is a horizontal painting, “Usuyuki” of 1982, a full-blown (and gorgeous) expression of the crosshatching technique he began to explore in 1977. The title, inspired by a Kabuki play, means “light snow” in Japanese. In three vertical sections, each with three stacked rows of three vertical units, “Usuyuki” is the largest work Johns made using the motif.

The latter part of the show, launched with “Céline” of 1978—a vertical work resembling a chalkboard on which the white, pale orange and pale green crosshatches of the top half spill into the lower half’s gray “flagstones” and a spearlike form juts up right of center—has a grim quality. A section called Nightmares chronicles Johns’s increasing use of motifs such as black handprints, skulls, cast arms and figures from Matthias Grünewald’s 16th-century Isenheim Altarpiece, which references the plague, as the AIDS crisis mounted in the 1980s.

A display of prints from the 1990s and later shows that Johns’s mastery of that medium continues to grow. But nearby drawings—and a Sculp-metal depiction—of cartoonish skeletons suggest that the mind of this protean creator has in recent years been occupied with a Dance of Death. One hopes that Johns finds solace in adding to his remarkable body of work, as so many of us do in the viewing.

—

For our previous review of the Jasper Johns retrospective’s other half, at the Whitney, see https://georgetowner.com/articles/2021/12/08/jasper-johns/