The Juneteenth Federal Holiday: A Backgrounder

By • June 16, 2022 0 2717

This Monday, June 20, is a U.S. national holiday commemorating “Juneteenth,” which falls this year on a Sunday, June 19. Many Americans are unsure, however, about the origins and significance of this federal holiday which President Biden signed into law only last year.

Where did Juneteenth come from?

Michael David of National Archive News provides the following origins: “On June 19, 1865, two and a half years after President Abraham Lincoln’s historic Emancipation Proclamation [Jan. 1, 1863], U.S. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3, which informed the people of Texas that all enslaved people were now free. This day has come to be known as Juneteenth, a combination of June and 19th. It is also called Freedom Day or Emancipation Day.”

While most understand that the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) resulted in the end of slavery in the United States, many are unaware that freedom did not come to the enslaved African American peoples in America all at once.

Before the war, President Lincoln called simply for the abolition of the spread of slavery to the west and not for its total abolition. Under the Constitution, Congress had the power to enact such restrictions on the spread of slavery, but the president did not have the authority simply to declare an end to slavery in the states by fiat. Following Lincoln’s election, however, 11 southern slaveholding states seceded from the United States of America and formed the Confederate States of America. After Confederate militias fired on Fort Sumter – a U.S. facility – in Charleston harbor, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, the Civil War commenced. With the war underway, President Lincoln now had Constitutional war powers as Commander-in-Chief allowing him to declare enslaved peoples free in the rebellious and insurrectionary states.

By Jan. 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring slaves “henceforth and forever free” in all Confederate states, but not in Union border states (Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware and Missouri) which still held slaves but had not seceded from the United States.

In the final days of the war, President Lincoln laid the groundwork for passage of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution legally abolishing “slavery and involuntary servitude” throughout all of the United States, ratified on Dec. 6, 1865, close to seven months after Lee’s surrender and Lincoln’s assassination.

Declaring enslaved peoples to be “free” and actually liberating them, however, were two separate propositions. Many enslaved peoples in the Confederacy either fled their enslavers via the Underground Railroad or awaited the arrival of Union troops who could help guarantee the enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation and freedom.

To avoid losing what they declared to be their “chattel property,” many White enslavers, however, carried their slaves beyond the reach of Union armies to areas, such as remote Texas. So, in Galveston Texas, two and a-half years passed before U.S. troops could enforce the liberating measures and U.S. Maj. General Granger could announce and secure the final ending of slavery in Texas.

On June 19, 1865, his General Order 3 liberating the enslaved peoples of Texas declared before jubilant Black audiences:

“The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer.”

Jubilee Celebrations

Celebrations of freedom spread through Texas in the years to follow. On June 19, 1866, former slaves returned to Galveston to celebrate “Jubilee Day.” Early celebrations centered on African and Texan-regional elements such as barbecued foods, “soul food,” rodeo, baseball, picnics, fishing, music and the singing of gospel spirituals. Gatherings often took place near rivers or streams or in the woods until later years when more public areas could be obtained. Black church celebrations also tended to include celebrations of education, with historical and religious instruction.

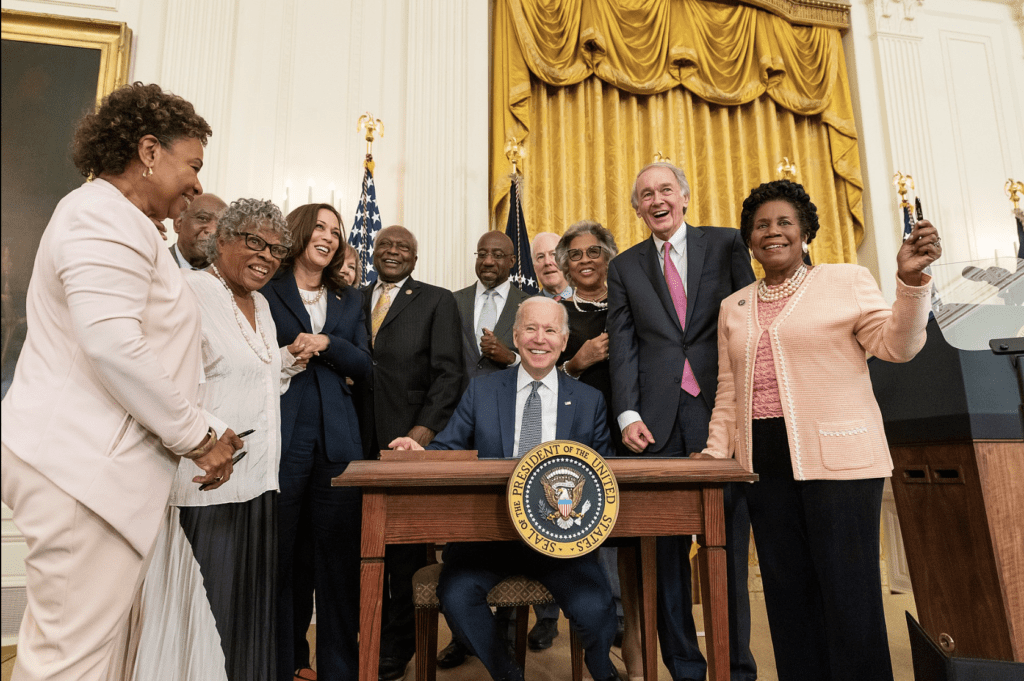

A few generations after the first Juneteenth celebrations in Texas, a 12-year old African American girl named Opal Lee enjoyed family celebrations of Juneteenth. But at the height of Jim Crow segregation in the south, a White mob torched her family home. She and her family didn’t let the intimidation slow her down, however. Lee became the foremost champion of celebrating Juneteenth nationally. During the signing ceremony for the holiday last year, President Biden, sitting near the nation’s first African American vice president, Kamala Harris, lauded Opal Lee, now 94 years old, calling her “incredible,” saying “hate never stopped her” and credited her with being the “grandmother of the movement to make Juneteenth a federal holiday.”

“African Americans understand that we can never take our freedom for granted because it has never fully, easily, or consistently been granted. Racial justice requires that others – particularly White Americans – understand this as well,” said Brenna Greer, professor of African American history at Wellesley College.

Harvard Law professor Annette Gordon-Reed, author of On Juneteenth, told Axios the holiday “Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the United States.” Having Juneteenth as a federal holiday will “really matter to young people, who will grow up seeing Juneteenth alongside July 4, Memorial Day and Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.”

“I would like to see [Juneteenth] evolve,” Gordon-Reed told National Archive News. “Where it’s not just a celebration but there would be educational things for young people to find out, to be encouraged to learn about the history of that time of what happened leading up to it and afterwards. I’d like to see it as a fun day but as an educational day as well. I would like to see it continue to be a day, not just for celebration, but a time for thinking about the serious issues that were involved here with the institution of slavery and the problem of racial discrimination. All of that is tied up in this day.”

The District celebrates its own Emancipation Day on April 16, commemorating the date slavery was abolished in the nation’s capital in 1862.