Rehabilitating The Washington Canoe Club

By • August 15, 2022 4 4802

In a race against nature’s destructive forces, Georgetown’s most prominent architectural feature and historic landmark on the Potomac River – the now-dilapidated Washington Canoe Club (WCC) – is on a path toward historic renovation, despite the inertial drag of inter-agency oversight.

In the nation’s capital, few river views are as captivating as the sight of Georgetown’s legendary green Victorian shingle-style boathouse at 3700 K St. NW designed in 1904 by 24-year-old architect George P. Hales (1880-1970) and built the following year. With a mission of providing “mutual improvement, the promotion of physical culture, and the art of canoeing,” the founders of the WCC wished to construct a boathouse for its private members similar to those along the Charles River in Boston. Having just arrived from Massachusetts and familiar with New England’s boating culture which had flourished in the Gilded Age as Americans embraced outdoor recreation, Hales – a canoeing enthusiast himself – was fit for the task.

The most iconic Potomac river views of Georgetown always include the Washington Canoe Club, built in 1905.

“The Victorian elements of New England boathouses and summer cottages — wood shingles, hipped roofs, gables, and capacious porches and balconies — would be incorporated in the WCC boathouse to achieve a blend of rusticity with comfort,” wrote historian Christopher N. Brown – who has personally paddled in all 50 states – in his book “Images of America: Washington Canoe Club.” For over 100 years, the Canoe Club has seen many additions, renovations and repairs. “Tradition holds that the clubhouse was built by the members, using salvaged timbers and lumber from burned barns,” the WCC website states.

The Washington Canoe Club was a hub of recreational activity on the Potomac River, sponsoring the President’s Cup in 1925. Courtesy WCC.

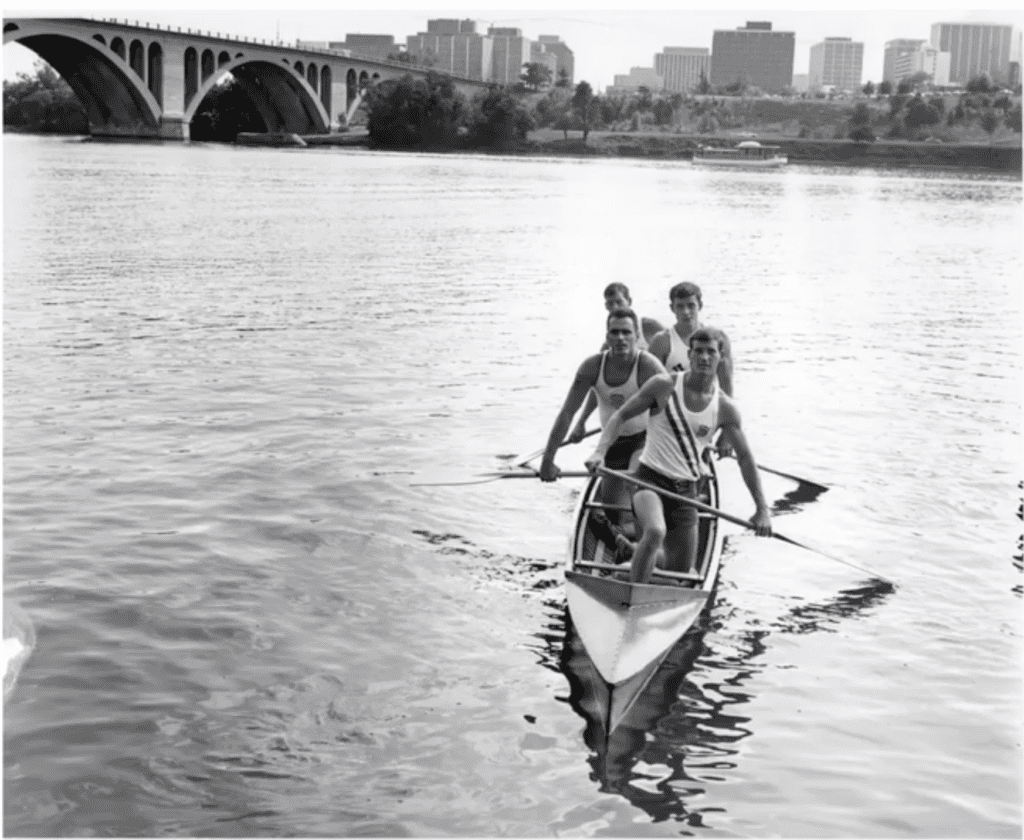

In 1991, the Canoe Club was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, cited as an architectural exemplar, one of only two remaining boat clubs along the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., (the other being the Potomac Boat Club just downstream) and the home of the nation’s premier flatwater paddle racing club. According to Brown, “WCC paddlers have succeeded at the highest levels of their sport. Twenty-eight members have been on Olympic teams, and the club has produced hundreds of national and international champions. Two WCC athletes have reached the pinnacle of amateur athletics glory, winning Olympic gold medals; two others have won silver. These WCCers are four of only nine Americans ever to win Olympic medals in flatwater paddling events.”

The WCC is the most celebrated canoe racing club in the United States. Paddlers returning to the docks, 1966. Courtesy Chris Brown and WCC.

Over the generations, the club has also significantly enhanced the social fabric of Georgetown, hosting ballroom dances, clambakes and grill parties, as well as a myriad of social and sporting clubs, and holding major swimming and boating regattas such as the President’s Cup established in 1925. The WCC has also been a leader in the nation in developing women’s paddling, adding a women’s locker room in 1930 and qualifying the first American woman, Ruth DeForest, for the 1952 Helsinki Olympics.

In 2014, WCC Women’s Outrigger Team wins 1st at the Liberty Challenge, NYC. WCC Twitter photo.

However, despite the historic significance of the WCC, many familiar with the boathouse’s years of struggles with wear-and-tear, flooding, ice jams, hurricanes, sun exposure, poor drainage, termites, and jerry-rigged repairs are afraid the aging boathouse could collapse or be swept away with the next major weather catastrophe before it can be refurbished to withstand the elements.

Today, the Canoe Club falls under the jurisdiction of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historic Park under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service (NPS). In 2011, the NPS – shocked by the condition of the club – sealed off the boathouse’s upper floors and balconies and installed internal bracing to prevent structural collapse. Five years ago, the WCC’s Rehabilitation Committee began working with the Georgetown architectural firm Cox, Graae and Spack (CGS) to develop plans for the club’s historic restoration.

The Georgetowner spoke with the head of the WCC’s Rehabilitation Committee, David Cottingham, and the principal CGS architect on the WCC account, Don Gregory, about the status of the Canoe Club’s rehabilitation efforts. What progress has been made and what challenges lie ahead?

In December 2017, Cottingham recalled, the WCC obtained a 60-year lease on the Canoe Club from the NPS. Now responsible for the building, the WCC knew the clock was ticking and the club had to focus on restoration. “So, we sat down with [CGS] and said ‘you know, the key thing we have to do is shore up the building… Because [it’s] in the flood plain – and guess what – these days with climate change and all that – we have to elevate… We’ve got to put on a new roof. We’ve got to secure the envelope,” Cottingham recalled. “And CGS came up with a good plan.”

A fundamental question: how to renovate while continuing to serve as a club for close to 300 members? Photo by John DeFerrari.

But the challenge would be to continue to allow the Canoe Club to function for its 300 or so members. “I mean, not just where we have boat storage, but where we can have social occasions and meetings, where we can have men’s and women’s locker rooms and those sorts of things. I mean, it’s sort of like an athletic club where people love to canoe and kayak,” Cottingham said. Cottingham’s been a member of the club “for about 15 years” and an “active whitewater and flatwater paddler for my whole life, basically… I’m getting ready to take my granddaughter over [to the club] for her first canoeing outing.”

For Cottingham, one of the biggest challenges in the restoration process involves the cumbersome approval process for historic restoration. Per the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act, federal historic restoration projects must take into account state and local concerns in what is known as the Section 106 Review. “We provide all this information first to the Park Service and then they coordinate the process. But they have all these different committees. And some meet on the second Tuesday, and some meet on the fourth Thursday,” Cottingham quipped. So, the WCC has contracted a consulting firm, EHT Traceries, to shepherd the WCC through the process. The firm has been “really smart” about how to proceed, he said.

Gregory and Cottingham both praised their NPS partners but helped clarify why the process inevitably takes so long. “Because the building is listed on the National Registry of Historic Places,” Cottingham said, “it has to go through, shall we say, considerable review – the Commission of Fine Arts, the Old Georgetown Board, the D.C. Office of Historic Preservation, the National Park Service, the National Trust and all of this. So, there’s a lot going on…. You have to get all this review done by all the different agencies… and it’s time consuming…. So, we’ve submitted all this material to them and we just got some additional material that we submitted in the last month or so to respond to some of the questions we got 4 or 5 months ago. So, it’s a back and forth, a give and take,” Cottingham said.

CGS Architect David Gregory agrees with Cottingham that the Section 106 process is cumbersome, but he still sees progress. “There are a lot of people looking at this,” he said. “It’s a National Registered building in a National Park in a local and national historic district. The National Park across the river, the George Washington Parkway, they’re also interested. What can they see from the GW Parkway?…. So, casts of thousands, literally, have been invited to sit in on these reviews…. I think there are several dozen Native American tribes that are invited… The Army Corps of Engineers because it’s on the water. It’s just that there’s a cluster of folks. It’s an established process we have to go through. It’s a challenge, but we’re wending our way.”

So far, the team has completed the first of the 3 scheduled Consulting Parties Meetings in the Section 106 process. The second such meeting has yet to be scheduled by the Park Service. “What we’re basically going through right now is the “Concept Design” phase,” Gregory said. Once the Section 106 process is complete, Gregory is confident CGS can handle the physical restoration. “We cut our teeth on adaptive reuse and historic preservation,” he said, describing CGS’s years of experience in restoration work, on contracts such as the Duke Ellington School of the Arts and Georgetown Visitation. “Our efforts [here] relative to architecture and engineering are not particularly difficult. It’s a process we’re going through with all the review agencies and parties that need to look at it. Once we have direction that the design is okay then we can move forward. And that will move pretty rapidly.”

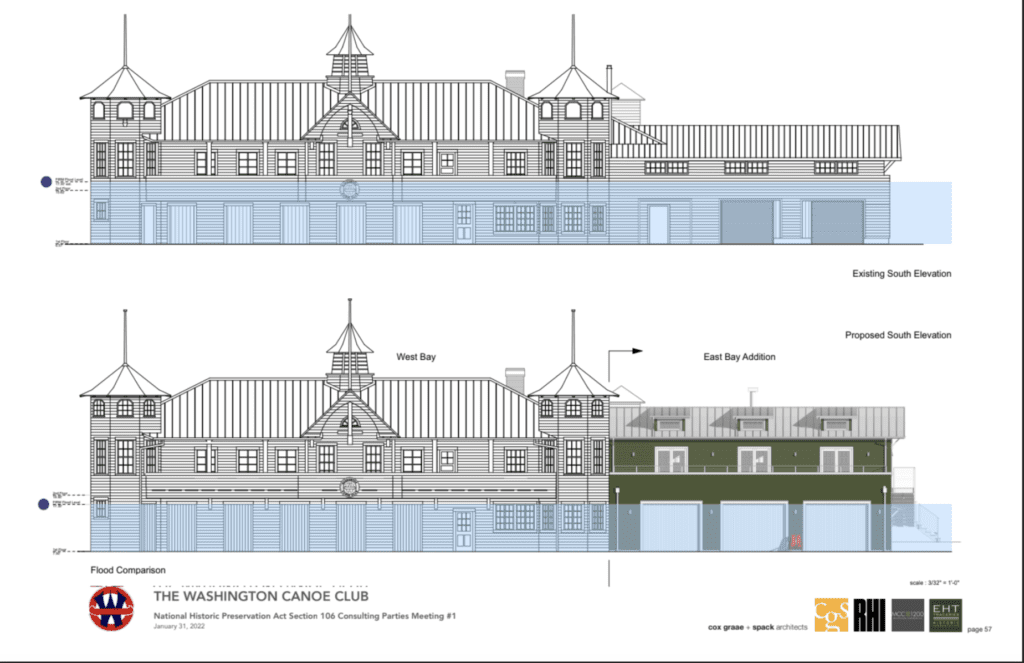

So, what’s the plan for the Canoe Club’s restoration? The first step is to raise the whole structure above the 100-year flood stage, approximately 32 inches. “The flood level at that point of the river is pretty high,” Gregory said. The 1936 flood and the one caused by Hurricane Agnes [in 1972] both submerged the second floor of the boathouse. So the plan is to “lift the building up and slide a new foundation underneath. And that will consist of piles that will go from the current floor level down to the bedrock. We’ll create a really thick slab with steel concrete columns and steel beams to support the second floor. Then we’ll lower the building back down on that new foundation of first floor structures.”

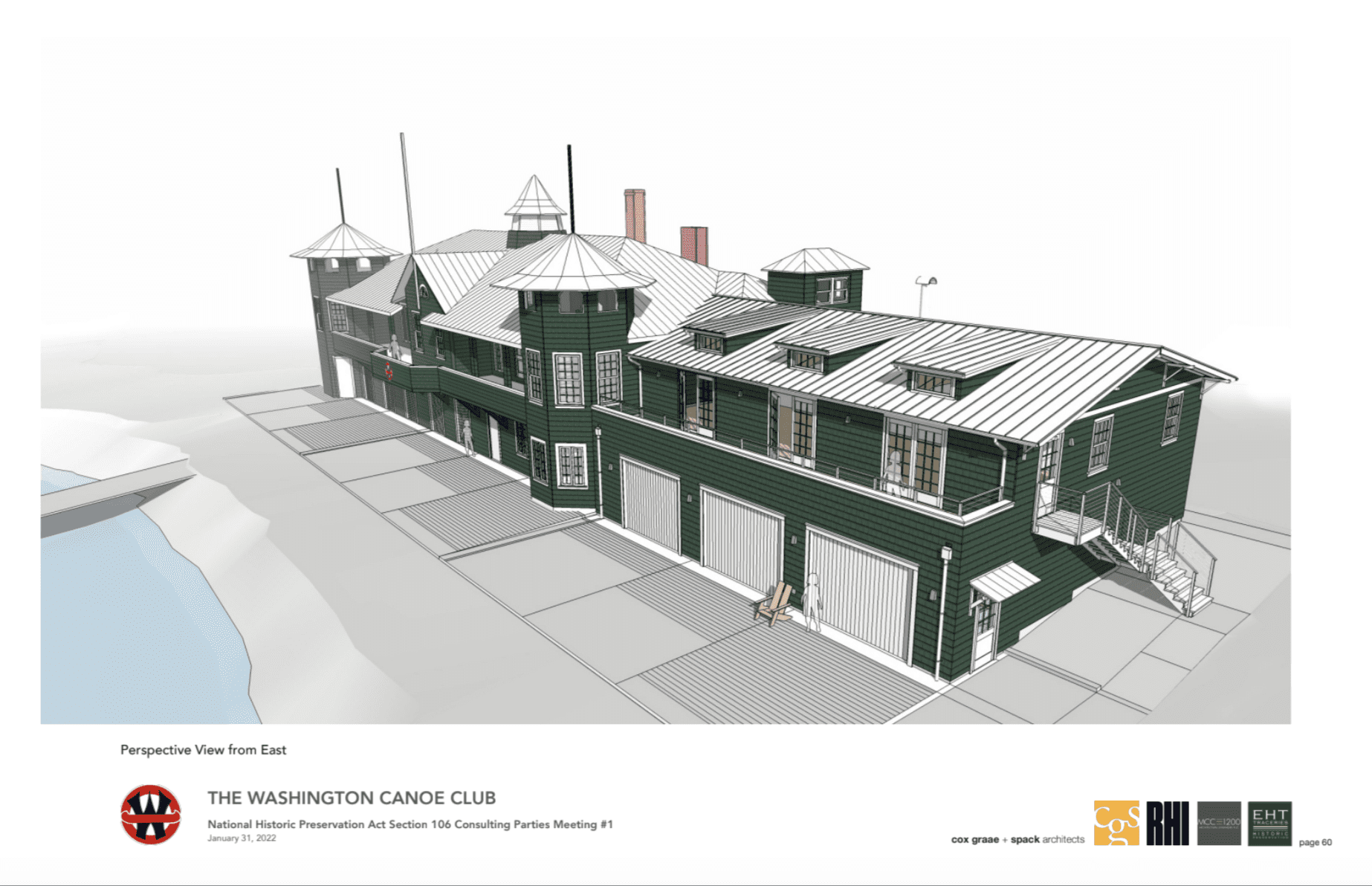

It’s time to rebuild and raise the East Bay! Before and after renderings of the Canoe Club’s restoration in the current “design concept” phase. Courtesy CGS Architects.

While the building is elevated, structural repairs and renovations can be performed. “It’s a relatively light structure because it’s wood framed. So, they’ll just pick it up and set it back down on its new foundation. Any structural issues the building has will be taken care of at that time as well… Everything upriver from the southernmost turret will be lifted up, made structurally sound, leveled – all that good stuff – and we’ll do restoration of the exterior. So, roofing, siding, shingling, windows, etc. So, it will look like a brand new building on the outside.”

Dual-action bay doors will be installed to reduce water pressure and allow the building to be drained following any flooding. All electric utilities, telecommunications and other non-flood resistant features will be moved to the second floor in the new plan. The club’s grill room and gathering space plus a supporting kitchen will be moved upstairs. The existing grill room’s famous 26-panel, 67-foot frieze painted in 1910 by Washington Star cartoonist Felix Mahoney (1867-1939) depicting in caricature many of the original members of the club carousing, paddling, and drinking beer will also be moved upstairs.

The more audacious aspect of the plan is to demolish and rebuild the entire East Bay of the boathouse on the club’s downstream side. Since only “about 14 percent of the structure” still contains historic materials worth preserving, Gregory believes this design concept will be approved in the Section 106 process. “We’ve gone through the survey process with our structural engineer to ascertain all these numbers and that submittal package has gone over to the Park Service and will go over soon to the other historic agencies.” If the proposal to rebuild the East Bay is approved, the plan is to “add facilities to the second floor,” such as a “new women’s locker room that’s ADA accessible.”

The East Bay (on the right of the current boathouse as viewed from the water) will be demolished and rebuilt with a blend of historic and modern elements. But mostly, to resist flooding. Courtesy CGS Architects.

From an historic preservation angle, the challenge will be to “not blur the lines between the old and the new,” Gregory said. “In the past, you’d kind of replicate what was on the site with an addition.” At the same time, he reassured, “we’re not going to put a glass box next to an historic building.” So, the East Bay will be built back as “recognizable as shingle-style,” but with some “details that will make it a little more commensurate with modern architecture.” Basically, however, it will be a “rectangular box with three big doors for boats on the bottom.” Questions such as whether shingles should be replaced with horizontal siding, roof height, changes of color, or even placing photovoltaic solar panels on the new structure are all to be decided, though Gregory said the solar installations might be “a little bit of a challenge as far as the Park Service is concerned.”

Depending on the club’s ability to fundraise, a later phase of the project will then involve the “final restoration” of the original west end of the boathouse, both interior and exterior, plus extensive drainage work to channel away leaking water from the C&O Canal. “We’ll want to be careful to not impact the Capital Crescent Trail [which runs just above the boathouse] in any way,” Gregory reassured. “That’s a highly used path for commuters and recreation. I actually use it when I go to work.”

On the question of fundraising, David Cottingham of the WWC estimates costs for the first phase of the restoration project to run from $7-8 million. However, rising inflation will present a challenge. While the “National Park Service hasn’t kicked in a dime yet,” Cottingham joked, “if some sugar daddy wants to come in and write us a $5 million check, we won’t have” to raise club member’s dues. “The Park Service and the Historic Preservation people generally like what we’re doing. We’re restoring an epic, iconic building on the D.C. waterfront. I wish all of them would come up with some money to help us,” Cottingham added.

“We’re at times tired or exasperated by the process…. But, we understand, people need to be heard. And there is a process to go through. But, we’re anxious to get it done for the club and to protect it,” Gregory said.

“In my ideal world we probably break ground in the fall of 2023,” Cottingham ventured.

On Saturday, September 17, the Washington Canoe Club will host a Sunset Dinner to fundraise for renovations. Go to Washingtoncanoeclub.org for more information.

I love seeing the dedication to preserving the boat house! I was part of an girl’s WCC War Canoe team during the mid-’60s. We goofed around a lot, practiced seriously sometimes, and participated in the President’s Regatta (I think that is what it was called). And there was an annual dance – so fun – wonderful memories!

Great article by Chris Jones.

Thank you so much, Barbara!

I would love to see DC and Arlington invest more in their waterfronts. There is so much missed potential! Rosslyn and Crystal City should turn to face the water more. It’s good to see investment in the Canoe Club (although the bureaucracy sounds like a nightmare).