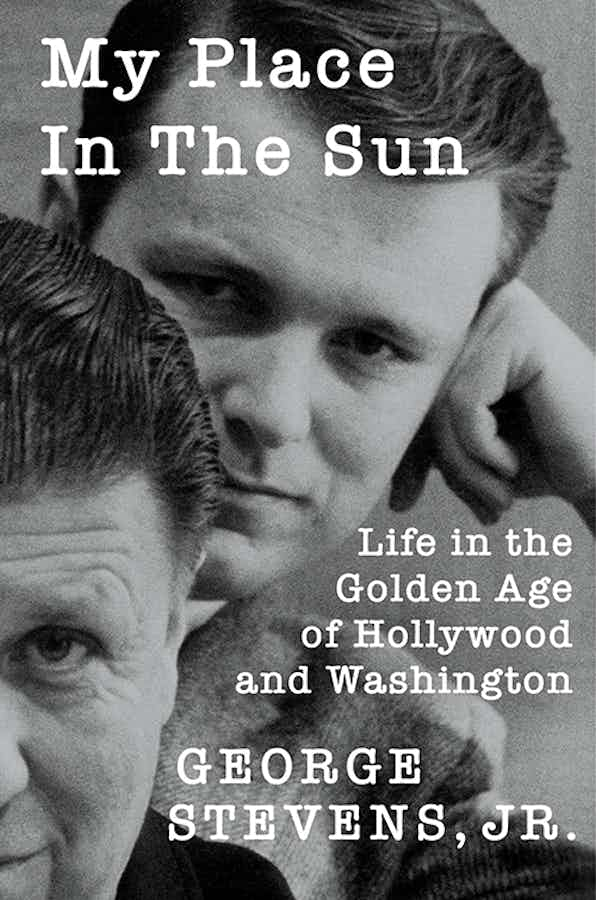

Kitty Kelley Book Club: ‘My Place in the Sun: Life in the Golden Age of Hollywood and Washington’

By • August 17, 2022 0 1591

Meet a fortunate son genuinely grateful for his luck.

Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

Sometimes, the sons of famous fathers are cursed. “They’re born on third base and think they’ve hit a triple,” according to the adage. Seldom do they hit a home run. Not so the namesake of director, producer, screenwriter and cinematographer George Stevens (1904-1975), who elevated films from entertainment to enlightenment with “A Place in the Sun,” “Shane,” “Giant,” “The Diary of Anne Frank” and “The Greatest Story Ever Told.”

His son — “Young George,” “Georgie” or “George, Jr.” — was born on third base, but now he’s nearly 90 years old and is proudly waving his scorecard in “My Place In The Sun: Life in the Golden Age of Hollywood and Washington.”

George Stevens Jr. is Tinsel Town royalty. He springs from five generations of stage actors, silent screen stars and drama critics, including his father. Stevens père, a two-time Academy Award winner, was a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during WWII and headed a film unit that documented the D-Day landings at Normandy, the liberation of Paris and the Allied discoveries of the Duben labor camp and the concentration camp at Dachau.

Stevens fils found these treasures and more in his late father’s storage bin and put them to good use in this work, a phenomenal history of Hollywood that’s as much a paean to a beloved father as it is an accomplished record of the adoring son, who propelled the family legacy forward into television (at 27, George Jr. was directing “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” for CBS) and prize-winning documentaries. In addition, he founded the American Film Institute (AFI) in 1966 and, for 38 years, produced “The Kennedy Center Honors.”

There are more names dropped in this memoir than in the Book of Jehovah. “Bobby and Ethel”; “My good friend, Tom Brokaw”; “Teddy”; “My rabbi, Vernon Jordan”; and “My buddy Art Buchwald.” One wonders if Stevens has ever known a no-name plumber or lowly key grip. Here’s just a sample of his life on the celebrity circuit:

“My calendar shows days filled with organizing a new [film] school and stimulating evenings during which I spread word about AFI to the Hollywood community; ‘Dinner at the [Gregory] Pecks — Mr. and Mrs. Jean Renoir, Omar Sharif and Barbra Streisand; dinner at home — John Huston and Shirley MacLaine; dinner at Danny Kaye’s with Pecks and Isaac Stern; dinner at George Englund’s w/Warren Beatty, Paul Newman, Robert Towne.’ ”

Despite the marquee names (and there are pages of them), there is no braggadocio. In fact, there’s a bit of the fanboy in this man who once asked President Clinton to sign their scorecard after playing golf together. George Stevens Jr. displays the self-deprecating style of someone enthralled by his work, engaged by his politics and enriched by his friends. His memoir, gracefully written, shows a man who knows that blessings accrue to those who take the high road.

Accustomed to flying smooth skies, Stevens was not prepared for the turbulence he encountered when David M. Rubenstein, chair of the Kennedy Center, forced him out as producer of “The Kennedy Center Honors.” Stevens writes that Rubenstein came to his office on a Good Friday in what “proved to be a disturbing and somewhat bizarre meeting…[Rubenstein] seemed to apologize, saying this was his most difficult meeting since the time he fired George H.W. Bush and James A. Baker from his Carlyle enterprise.” He continues:

“Again, insufficient paranoia had let me down. David’s riches, after all, had come from hostile takeovers of corporations — ousting existing management, cutting costs and reaping windfalls. On reflection, my response was less tempered than I would have liked. ‘I think you’ll have to look around for a long time to find producers who will give you five consecutive Emmys.’ ”

Since parting ways with the Stevens Company in 2014, “The Kennedy Center Honors” has won a few Emmys but not yet “five consecutive” ones. For his part, Stevens writes, “It’s too bad it ended the way it did, but the passage of time now allows me to look back on the somewhat indecorous circumstances of my departure with what Wordsworth called ‘emotion recollected in tranquility.’ ”

Just when the reader is floating on the sweet vapors of a golden life among the good and the great, Stevens brings you to your knees with the worst that can befall a parent. In 2015, he and his wife, Elizabeth, lost their 49-year-old son, Michael, to stomach cancer. This chapter, entitled “Courage,” is a chapter no parent ever wants to write. Stevens keeps it short:

“Not a day goes by that I do not think of Michael Stevens.”

He ends his book as he began it — by extolling the work that has defined his life for decades. He quotes Bertrand Russell, who wrote about the same subject at the same age in “The Pros and Cons of Reaching Ninety”: “A long habit of work with some purpose that one believes is important is a hard habit to break.”

Last seen, Stevens was heading for his office “to ponder stories that might become films, though an awareness that each new film is a commitment of years makes me a little less keen to toss my cap over the wall. However, now that the storytelling juices that have been devoted to this book are freed up, who knows what lies ahead.”

We can only hope.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.” She serves on the board of BIO (Biographers International Organization) and Washington Independent Review of Books, where this review originally appeared.