Exclusive Interview on the Migrant Crisis: Woman Walks From Ecuador to Texas

By • August 29, 2022 One Comment 2219

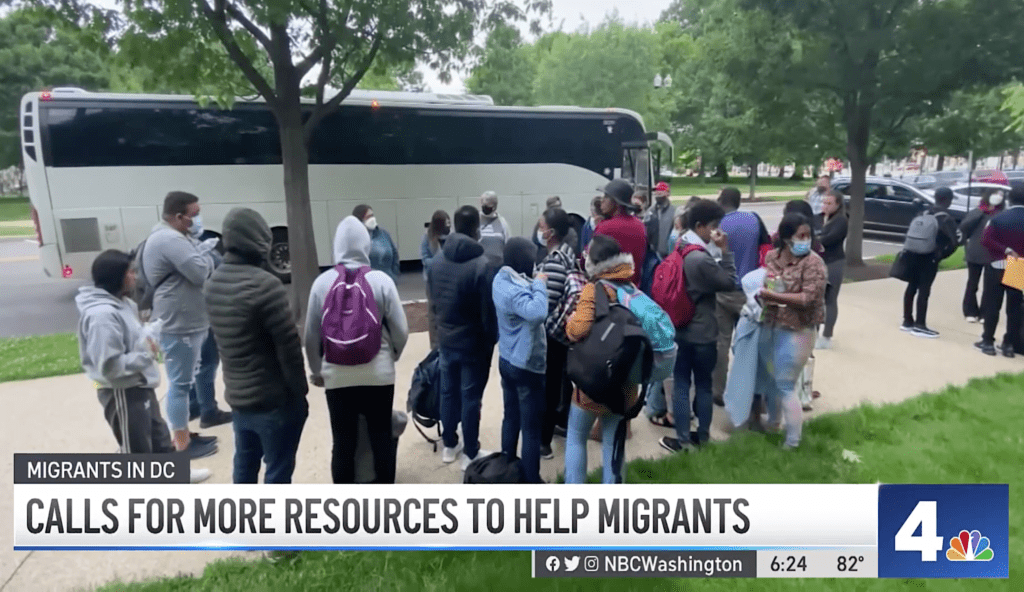

Recently, I asked the president of a large Democratic women’s organization in Washington, D.C., if they had been helping any of the more than 6,000 migrants who had been bussed to D.C. from Texas in recent weeks. Many D.C. charities and immigrant rights groups have tried to help, but their resources were overwhelmed. Most of the migrants — usually single male adults ages 18 to 26 — have ended up on the streets. Mayor Muriel Bowser has asked the National Guard for help. She was refused.

The non-profit’s president enthusiastically introduced me to a 26-year-old woman helping in their food bank. She had walked from Ecuador to Texas in 45 days in May and June, then took the offer of a free bus from Texas to D.C. in early July. The former Venezuelan naval helicopter pilot student was eager to tell me her story over a two-hour lunch — speaking only Spanish. But she asked me not to use her name since she didn’t have papers. I must tell you she is beautiful. Her lovely hair fell in swooping curls and she had long manicured fingernails. In her soft but passionate voice, she told me that she was still upset and traumatized by her trip. But she also acknowledged she had been very lucky to make it to the USA safely and to find a hostess in D.C.

I recount her story here from my notes in Spanish and English. Her narrative brings up as many questions as it answers.

“I am from a coastal town in Venezuela where my parents had a small construction supply business. Seven years ago, I joined the navy. A year or so after, I was happy to be accepted into the helicopter pilot training program. I wanted to do something different, that most girls don’t do. During the governmental incursions of 2017-18, I had to do some security detail with my naval unit. That was OK. But then about four years ago, my parents were taken hostage in their home and all their belongings were taken away. We decided as a family to flee to Ecuador. I eventually became a nail technician, although it’s not what I wanted to do. I wanted to go to the United States where the jobs were better.”

“This May after preparing with five friends — all male — we started off from Ecuador to walk to the U.S. – ‘al norte.’ I knew we had to travel light so I only took a small backpack with some clothes.”

“How many shoes did you take?” I asked. “Only one,” she replied. “My sports shoes.” “How are they?” I asked. “Fine,” she answered with a shrug.

“What was the worst part of the trip?” I inquired. “Oh, the Darien jungle in Columbia before Panama,” she answered without hesitation. “If you can’t afford a boat around it, you have to walk through it. It was very scary. No food or water. Took about a week. We saw almost no one.”

More questions: Did you have guides? maps? Did people help you with food and transportation? Were you ever assaulted?

“No, I was never assaulted,” she maintained throughout the two-hour interview. “My friends protected me. And several times during the trip we were able to pay for a bus, or a hotel or for some meals. Sometimes, people helped us.”

But they did have to pay bribes. Usually to people in (fake?) uniforms. “Mexico was the hardest border to get through,” she said. “I was ‘kidnapped’ in central Mexico” — she used the verb “kidnapped” in English a couple of times, but we agreed that she meant more like “taken hostage” or “detained” — until she paid a bribe. The biggest bribe she paid was in Mexico: $600.

“How much money did you take with you?” I asked. “About 1,200 American dollars,” she said.

“So, what happened when you got to the Mexican-U.S. border?” I asked. “We took a bus and had a map to the Rio Grande river crossing. It was dark but there were about 600 people waiting there — the most we had seen on the whole trip,” she recounted.

No one guided or led them. At one point during the night, people started wading across the river. So, she and her friends decided to as well. “The water was deep, up to here,” she showed me pointing to her chest. “It was hard because I had hurt my ankle. I was scared.”

When she and her friends made it onto the Texas shore, however, uniformed U.S. border patrol came up to them. “Are you OK?” she recalled was the first thing they asked. “Are you hurt? Hungry? Need water?”

Then, they were taken by van to a registration center. “They asked us for our names and nationality,” the Venezuelan citizen said. She had no papers to show them (had been told not to bring any). No one asked anything about COVID.

Then, people from ISAP (Intensive Supervision of Appearance Program, a government migrant monitoring program) took charge. “We have automatically registered you as claiming asylum,” they told her and her friends. “We will help you with the paperwork.”

“Did you see anyone turned away by the border patrol?” I asked? “No,” she said firmly.

The agents then took them to a small tent city where they were given food, clean clothes, a chance to shower and clean beds. Her companions were already contacting relatives and friends they had in Texas, California and Chicago. But she had no one to call. A few days later, they were given a bus ride to a small Texas town and told they were free to go where they wanted. As she walked into town, people from another organization told her they were putting together a bus for migrants to travel free to Washington D.C. “Would she like to go?” She immediately said yes.

The bus arrived at Union Station 45 hours later. It was late at night and dark. A small number of people greeted them with food and water. Some migrants — mostly women and a few with young children — were offered to stay at volunteer’s homes for a night or two, but no more. They would be directed to agencies that could help them.

Then, she got really lucky. One of the volunteers said she could stay with her. “Now I’m doing all I can to expedite my asylum status so I can get a job permit,” she said. “That’s what I want. A good job and security to stay.”

I told her I was happy for her and wished her luck. I didn’t mention that because she was coming from Ecuador where she and her family had found safe refuge, a home and jobs for over three years, that might taint her request for asylum status. But Venezuelans have been given special Temporary Protective Status on the basis of their nationality — it is not safe for them to go back to their homeland right now (a United Nations Human Right). So, she might not have to prove she was fleeing immediate mortal danger as asylum and refugee applicants usually are required to do.

Such are the realities of crossing the southern border. Meanwhile, nonprofits in D.C. that assist migrants arriving from Texas are running out of resources and are asking for help themselves.

thanks about this article good