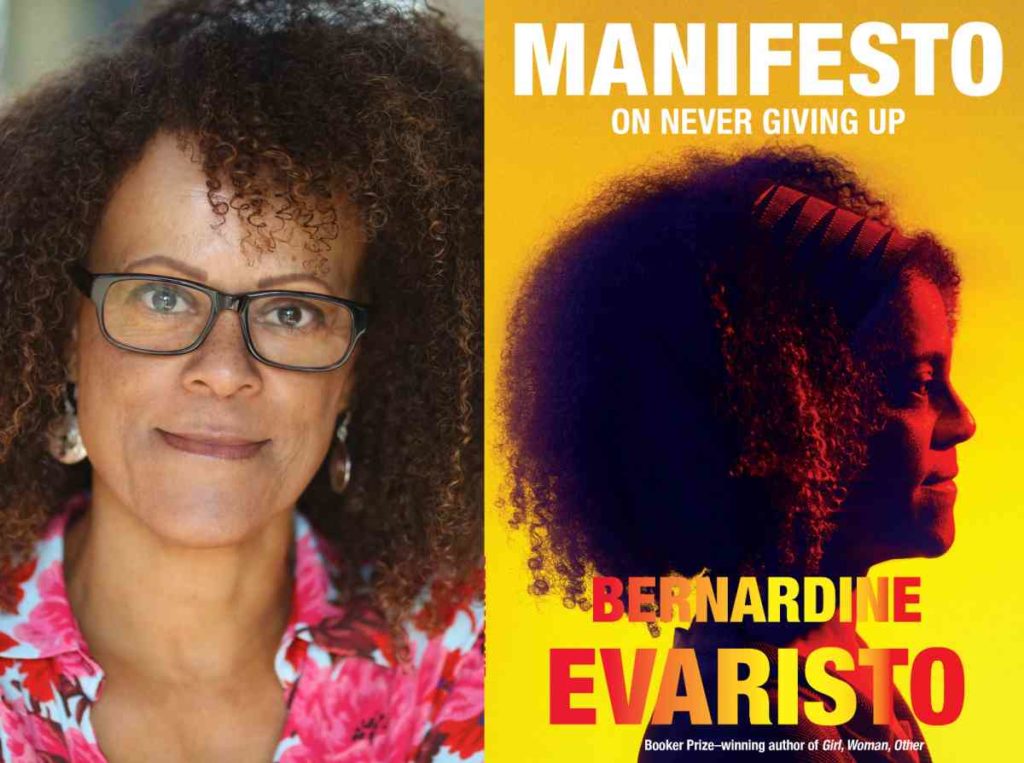

Kitty Kelley Book Club: ‘Manifesto: On Never Giving Up’

By • October 12, 2022 0 1326

The Booker Prize-winning author owes it all to tenacity. And talent.

Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

If “perseverance is genius in disguise,” then Bernardine Evaristo is a 22-carat gold, diamond-encrusted genius. She is the patron saint of persistence and proves it with her ninth book, “Manifesto: On Never Giving Up.” Having received the 2019 Booker Prize for her novel “Girl, Woman, Other,” Evaristo was the first Black woman and the first Black Brit to win the prize in its 50-year history. So she now has a global audience for her gospel on persevering.

In this “Manifesto,” she offers insights into her biracial heritage (white English mother and Black Nigerian father), her “lower class” childhood (number four of eight children) in London, where she was considered by the British class system to be “inferior, marginal, negligible,” and her personal relationships (10 years living as a lesbian followed by a heterosexual marriage).

Whether homosexual or hetero, she was always a feminist and approached her struggle for success with a winning strategy: persistence — no matter what. “I’ve always felt myself to have an inner strength, by which I mean that I’m not needy or clingy. I don’t crave approval all the time… a tough inner core has been essential to my creative survival.”

In a chapter entitled “The women and men who came and went,” Evaristo expends several pages on what she calls her “lesbian era,” because she feels the problem is not with same-sex attraction but with a homophobic society that requires queer people to justify their existence. “Put it this way: my lesbian identity was the stuffing in a heterosexual sandwich.” In 2005, on a dating website, she met her husband, whom she describes as “a white middle-class man.” She portrays their marriage as a life preserver that freed her to get on with her most important work — writing.

Readers might wince as they read of Evaristo growing up Catholic, biracial and brown-skinned in an overwhelmingly white Protestant area, enduring the name-calling of neighbors and the dismissals of the “unholy men… the half-drunk priests” who heard her confession every week:

“In my family, we had no doubts about the hypocrisy of the Catholic clergy, and as we each reached the age of fifteen, after ten years of attending Sunday Mass, my siblings and I were given the choice whether to continue or not. One by one we left the church never to return; as did my mother in due course.”

Evaristo began her creative journey by writing poetry; after college, she started writing and acting in the Theater of Black Women, Britain’s first such company. To survive, she lived on the dole and by her wits:

“I moved into slummy old properties, ready for demolition… A futon served as both sofa and bed. Boxes for clothes. Planks of wood and bricks became a bookcase… I prided myself on being able to stuff the rest of my meager possessions — clothes, books, bedding, kitchen utensils — into a few black rubbish bags.”

Leaving the theater in her 30s, Evaristo concentrated her creative energies on writing with London as her muse, having lived so many years in the city’s various districts. Finally, at the age of 55, she bound herself to a mortgage and settled into a life of writing, writing, writing. “I had become unstoppable with my creativity… writing became my permanent home.”

Now 63, Evaristo is unsparing about her own racism. As a child, she was ashamed of her father’s very dark skin. “I remember crossing the road when I saw him walking towards me. It was internalized racism, pure and simple… Black was bad and white was good. As a child I’d have killed to be white, with long blonde hair.”

She addresses “colorism or shadism,” and notes that, “sadly,” some people choose to pass because they’re light enough to be racialized as white, such as the Hollywood stars Carol Channing and Merle Oberon.

Throughout her life, Evaristo believed in herself and her talent, even when others did not. “[This] self-belief… is the single most important thing a writer needs, especially when the encouragement we crave from others is not forthcoming.”

The last section of her book, entitled “The self, ambition, transformation, activism,” echoes the principles of “Psycho-Cybernetics” by Maxwell Maltz, M.D., which was published in 1960 and sold more than 30 million copies. The biracial British writer and the late Jewish American physician share the same philosophy: Envision the goal, believe you can accomplish the goal and then achieve the goal.

When Bernardine Evaristo wrote her first novel, “Lara,” in 1997, she wrote, in part, an affirmation about winning the Booker Prize. Twenty-two years and eight books later, she finally received it. Dreams really do come true.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.” She serves on the board of BIO (Biographers International Organization) and Washington Independent Review of Books, where this review originally appeared.