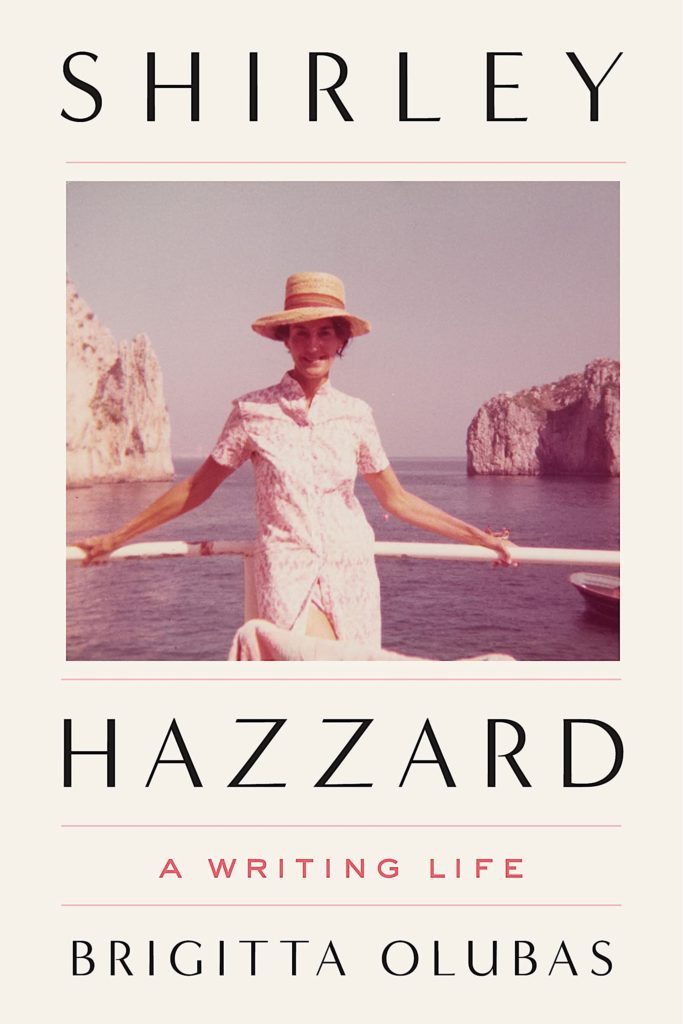

Kitty Kelley Book Club: ‘Shirley Hazzard: a Writing Life’

By • December 1, 2022 0 1960

An entertaining, edifying look at the underappreciated Australian author

Shirley Hazzard’s first short-story submission was plucked from a slush pile of 30,000 unsolicited manuscripts at the New Yorker by fiction editor William Maxwell. And then, just like an unknown Lana Turner being discovered while sipping a soda at Schwab’s drugstore, a star was born. The Hollywood star married eight times, and the writer only once, but Hazzard wrote about love the way Turner pursued it — as something perishable that, in the reshaping of our minds, becomes permanent: “the only state” in which “all one’s capacities are engaged.”

(So ends the stretched connection between the MGM star from Idaho and the Australian writer who moved to New York in her 20s and eventually traveled in the city’s intellectual circles with Lionel Trilling, Muriel Spark, Alfred Kazin and Dwight MacDonald.)

Shirley Hazzard (1931-2016) died at 85, sadly of dementia, but left behind six books of nonfiction, four novels (“The Transit of Venus” being her masterpiece) and two story collections. In two of her nonfiction books, she blasted the United Nations, where she had worked in the “dungeons” for several years. She emerged from that experience disillusioned and dyspeptic, and lambasted its supporters, including Margaret Mead and U.N. Under-Secretary-General Brian Urquhart. He, in turn, dismissed Hazzard as a no-nothing, unpaid secretary.

In 1980, she wrote an article for the New Republic exposing the Nazi past of Kurt Waldheim, which had allowed him to rise to become U.N. secretary-general from 1972-1981 and president of Austria from 1986-1992. Hazzard’s exposé failed to galvanize public attention, but things changed five years later when writer Jane Kramer expanded on Hazzard’s Waldheim revelations.

At first, Hazzard was offended at having been overlooked in bringing the story to light but was “slightly mollified” when Kramer wrote to her: “You deserve enormous credit for being… as I now know the only person to have persisted in publishing the truth about that odious man over all these years when it was convenient to pretend he was decent.”

Hazzard’s fiction garnered impressive prizes, including the O. Henry Award, National Book Award, William Dean Howells Medal, Miles Franklin Award and National Book Critics Circle Award. Yet for all her literary achievements, she was not as celebrated as some think she deserves to be, and that includes her biographer, Brigitta Olubas.

A literary scholar at the University of South Wales, Olubas has been researching her subject for three decades. Among other works, Olubas wrote “Cosmopolitanism in the Work of Shirley Hazzard” (2010); “Shirley Hazzard’s Capri” (2014); “The Short Fiction of Shirley Hazzard” (2018); and “Shirley Hazzard’s Post-War World” (2020). Now comes “Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life,” Olubas’s full-throated chronicle of the writer advertised as “the first biography of… a writer of ‘shocking wisdom’ and ‘intellectual thrill.’ ” Those last two quotes come from a 2020 New Yorker profile of Hazzard and are heartily underscored in this work.

Olubas seems determined to prove that Hazzard is to Australia what Joan Didion is to America: a literary icon. Growing up in Sydney with a bipolar mother and an alcoholic father, Hazzard was devastated when her family had to move to New Zealand because her sister, her only sibling, was ill with tuberculosis. As a youngster, Hazzard was surrounded by wounded WWI veterans, and she saw the devastation of Hiroshima at 16, which infused her novels with inevitable loss.

Her later years with husband Francis Steegmuller, a quarter-century her senior, were her happiest and most creative. Steegmuller, a Flaubert scholar, and Hazzard divided their lives between Capri and Manhattan, becoming significant figures in their rarified circle of academics, poets and writers. During this time, they befriended Graham Greene, a relationship Hazzard later memorialized in “Greene on Capri.” Yet Greene’s widow later dismissed Hazzard as a know-it-all harpy and claimed her husband felt Hazzard “intruded herself too much” and “had a tendency to talk a great deal.”

Olubas describes Hazzard, with her limited formal education, as “an exquisite stylist, skilled linguist and fiercely intellectual autodidact.” She acknowledges Hazzard’s dominant (at times domineering) personality and insistence on commandeering conversations and reciting endless reams of poetry. Hazzard spoke in long paragraphs, as if being filmed; she disliked television and read Herodotus over lunch. She commanded attention in her starched shirts, Chanel tweeds, and a beret that covered her teased bouffant. She bemoaned growing old, especially during her last years as a widow, ailing and alone.

Given complete access to Hazzard’s diaries and journals, Olubas was able to climb into her subject’s mind and heart and find the answers to how Hazzard felt at various times and why she said what she said and did what she did — the kinds of questions that perplex many biographers, forcing them to guess and surmise. Brigitta Olubas has made glorious use of her years as a Shirley Hazzard scholar, too, and in this biography, she eloquently presents all that was won and lost in Hazzard’s writing life.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.” She serves on the board of BIO (Biographers International Organization) and Washington Independent Review of Books, where this review originally appeared.