‘Philip Guston Now’ at the National Gallery of Art

By • March 8, 2023 0 3134

“Philip Guston Now” is one of those rare and remarkable exhibitions that manages to be all things at once. It’s a focused retrospective, a beautifully told story of a singular artist. It’s a window into our own history and a mirror onto our present moment that avoids ponderous didactics and cheap comparisons. It is a survey of Western art history in microcosm — from the Renaissance through postmodernism (and newspaper comics). It’s a love letter to the presence of art, to paint, to museums, to preposterously huge canvases on even huger walls.

It is surprising, revealing, funny, sad, mesmerizing and relatable. It’s awesome.

Maybe I should confess my bias. Philip Guston is one of my favorite painters, and I’ve been anticipating this exhibition for about a decade, and throughout the years-long delays due to the pandemic and further complications related to the Black Lives Matter revolution. The latter precipitated a moral reckoning, a crisis of faith and a foundational restructuring among arts institutions across the country. There was a moment there when this exhibition, another celebration of a dead white man, was almost certainly on the chopping block.

Thankfully, the exhibition prevailed — in no small part because Guston’s own biography subsumes perfectly into the combustible sociopolitical ether our country now occupies.

Born in 1913 in Montreal to Jewish parents who had fled persecution in Ukraine, Guston was a self-taught artist and intellectual with a high school diploma. When his family moved to Los Angeles in 1922, he was surrounded by racism and antisemitism. Los Angeles was politically dominated by the Ku Klux Klan in the twenties and thirties — John Clinton Porter, the city’s Mayor from 1929-1933, was even a local Klan leader (seriously).

In 1935 — like many American Jews with ambition and aspiration (including my own grandfather) — he changed his name. “Goldstein” became Guston.

He was politically radical, making socially conscious murals and antiwar paintings in a kaleidoscopic style that fused influences from Hellenism and the Venetian Renaissance to Cubism and great modern muralists like Thomas Hart Benton and Diego Rivera.

Interestingly, despite being intrinsic to Abstract Expressionism in retrospect, Guston wasn’t actually there during its genesis in 1940s New York City. While his high school classmate Jackson Pollock and all the other AbEx legends were inventing abstraction in Greenwich Village, Guston was teaching art in Iowa to support his family and making politically charged representational paintings.

It was only when he moved to New York in the late forties that he discovered abstraction. But when he found it, he leaned in. His abstractions became a relief, a place where he was able to keep out the violence of the world.

Guston’s abstractions are pretty marvelous, happy, almost childlike — big, square canvases that bulge with color in the center and dissipate toward the edges. It was also during this time that he found his color palette — pastel pinks, reds and blues, punctuated by acid green and soda-pop orange — which he held onto for the rest of his life.

But eventually the outside world crept back in.

From the 1950s until the mid-sixties his palette gradually darkened and he was increasingly plagued by the urgency to deal in his work with the stuff of the world: wars, assassinations, protests, human rights, history. He clearly felt guilty bearing witness to the torment of the world and then going back to his studio to play with colors.

During this period, Guston visibly oscillates between abstraction and representation. His work looks physically conflicted. Black lines struggling for clarity and form, scratched across sheets of paper like messages from a purgatoried ghost.

Ultimately, figuration won out, but the thing that was birthed was bizarre, crude, challenging and almost universally condemned by critics. And it’s not hard to see why.

His paintings became a kind of phantasmagorical comic strip series, featuring two central characters: a hooded Klansman and a disembodied, bloodshot eyeball with a five o’clock shadow. They smoke cigarettes, paint stupid paintings, suffer from insomnia and generally loaf about in a kind of Looney Tunes ghetto. Sometimes God makes an appearance, a giant hand descending from of the sky, just to screw around.

These paintings, among other weird things, are nihilistic allusions to the staggering atrocities of the 20th century. Guston also seems to reject the slick cool of postmodernism in exchange for a proletariat visual language, siphoning influence from comic artists like George Herriman and Robert Crumb more than anything else. (There is also an entire separate exhibition in an adjacent set of galleries devoted, essentially, to Guston’s obsessive hatred of Richard Nixon.)

Together these paintings create a uniquely American fever dream. They are not pleasant. You would not want them hanging in your home. But they also might be the most relevant, engaged, empathetic, important and human paintings of their time.

Willem de Kooning was often hailed as the painter’s painter of his generation. An immigrant with classical arts training who came to this country as an illegal stowaway on a cargo ship from Rotterdam, de Kooning built a successful career as a designer in New York before giving it up to paint in relative destitution for twenty years. He felt the urgency of art and the transcendence of America in his bones. “Do you know what your real subject is?” he once said to Guston. “It’s freedom.”

“Philip Guston Now” runs through Aug. 27 at the National Gallery of Art .

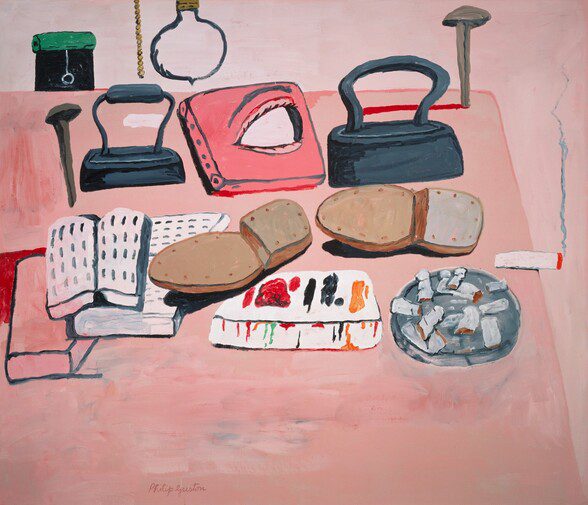

Philip Guston, “Painter’s Table,” 1973, oil on canvas.

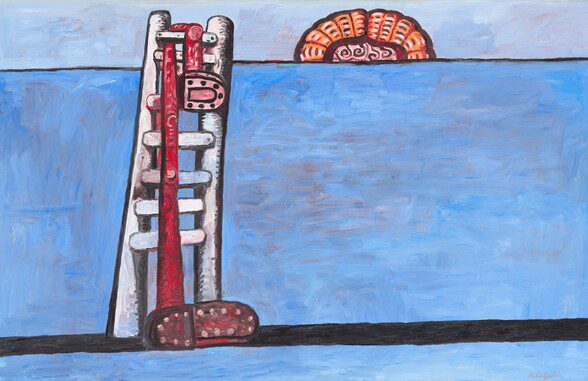

Philip Guston, “The Ladder,” 1978, oil on canvas. Gift of Edward R. Broida. Copyright, the Estate of Philip Guston.