At Home: The Bathtub

By • July 20, 2023 0 2043

In 1917, the renown newspaperman, H.L. Mencken, published an article titled “A Neglected Anniversary,” in which he described the curious history of bathtubs in America. The “facts” in his piece were completely made up, however. He later claimed that his hoax was just a wartime diversion from all the dreadful news about the First World War.

However fanciful Mencken’s claims – that bathing was controversial, that people found bathtubs too decadent, or unhealthy and that cities tried to ban bathtubs– in fact, most Americans did not bathe during the first part of the 19th century. It wasn’t until people noticed the link between poor sanitation and disease that the importance of regular bathing became apparent. In response, cities expanded water and sewage facilities and water was piped indoors. Even so, most American homes did not have indoor plumbing until the early 20th century.

Primitive cowboy bathtub made of galvanized metal, featuring back and arm rests, like many used throughout early America. Photo by 1st Dibs.

For decades the bathtub most Americans knew best was a tinware plunge bath with a wooden, painted bottom. Even though cast iron — a revolutionary material of the Victorian era — had been used on bathtubs since late 1850s, corrosion continued to be a big problem. By the 1860s, artisans cracked the tub-coating code by taking a different tack: all-ceramic tubs with a glazed surface.

In the 1890s, John Kohler invented the clawfoot free-standing bathtub. He took a cast iron horse trough, enameled, and glazed it and added four decorative feet to the bottom of the tub. As personal cleanliness became a greater concern and the process of enameling the tub helped to create a smooth surface that was easy to clean and prevented the spread of bacteria, clawfoot bathtubs became extremely popular. Since these glazed tubs were fragile and heavy, they were challenging to export from Europe to the United States, but, finally, Trenton Potteries in New Jersey, along with several other stateside manufacturers, started producing porcelain tubs for the American market. However, clawfoot bathtubs existed in only 1 percent of most homes by 1921, with outhouses still prevalent in rural areas.

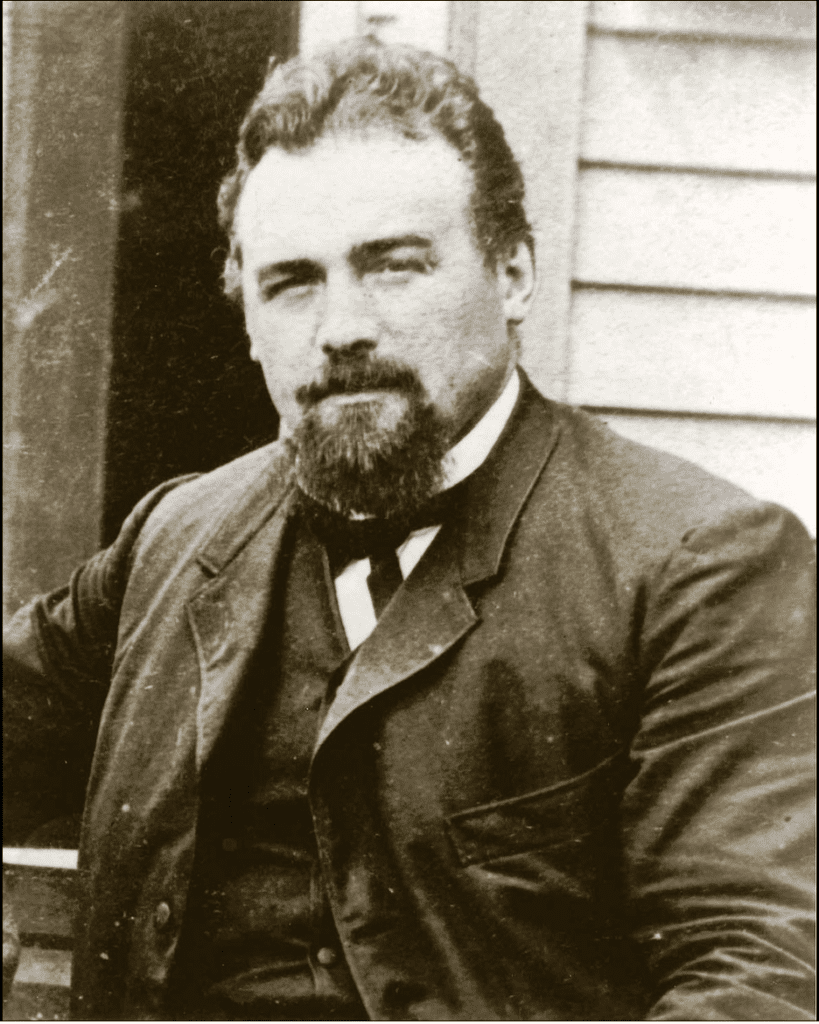

John Kohler. In the 1890s, he invented the clawfoot free-standing bathtub. Wikipedia photo.

And consider that although indoor water and bathtubs were more accessible to middle-class Americans during the 1890s through the 1920s, 97 percent of tenement dwellers did not have such access. Clean was good, dirty was bad, “a moral failure as well as a threat to public health,” according to a newspaper article of the time. So, the continuing dirtiness of people who couldn’t afford their own bathtubs was a big enough public concern that free public bath houses became a campaign issue in New York City, ushering in a golden age of bathhouse construction. Between 1901 and 1914, 26 municipal bathhouses were built for tenement dwellers on the Lower East Side.

In this new century increasingly on the alert for germs, the solid porcelain tub remained the status symbol of the bath industry into the 1920s and the hallmark of high-end bathrooms. But, by 1911, the Kohler Company introduced a one-piece tub with a rim that extended down to the floor and the built-in, apron-front, drop-in bathtub became a staple of the modern home. These bathtubs, made with one enclosed side, were easier to construct and cleaner than the old Victorian-era clawfoot tubs.

Master bath at the Codman Estate in Lincoln, Massachusetts, part of the original manor house built in mid-1700s. Plumbing pipes are located outside the walls to minimize the damage to the original structure. Courtesy Historic New England.

As the bathtub and the bathroom morphed from being purely efficient and hygienic, they started to become a focal point for household design and around 1929, color came into the bathroom in a big way. Instead of the hospital-like, all-white fixtures, matching colorful bathtubs and toilets to tile and wallpaper became highly popular.

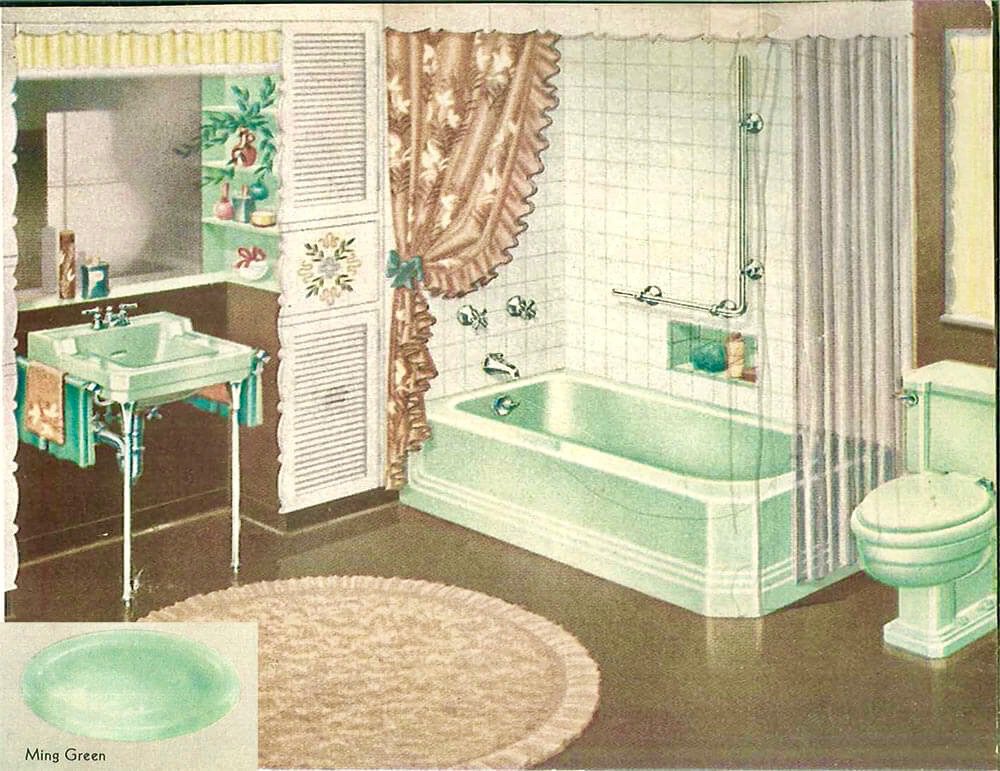

Companies perfected coloring the vitreous finish in their fixtures, and as fixtures became colorful in the 1930s and ’40s, they started to attract as much design interest in a home as did furniture. In the 1930’s, Ming Green was the name of the color often chosen for bathtubs, which were paired with peach and mauve tiles. In the 1940s, people preferred to use bright colors like royal blue. The big color of the 1950s was pink combined with gray tiles. Turquoise, Spring Green and teal were popular color choices in the 1960s. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, design magazines touted large tiles with unusual geometric patterns.

American bathrooms in the early-to-mid-20th century use various color combinations, including this 1930s Ming Green American Standard line. Internet Archive.

Then, in the early 2000s, bright colors in a bathroom lost their popularity. The color trend today is shifting back to the original elegance of pure white. Although contemporary homeowners still really love their vintage, old-school, colorful built-in tubs, many are replacing them with freestanding tubs. The freestanding soaking tub, a modern take on an old clawfoot tub design, has come roaring back. As are hygienic white and subtle neutral colors. You know the old saying – “what’s old is new again.”

Michelle Galler is a realtor with Chatel Real Estate, representing buyers and sellers in both Washington D.C .and Virginia with in-town, as well as rural, real estate transactions. She is also an antiques dealer and columnist.