PostClassical Ensemble Surveys Architecture

By • November 30, 2023 0 694

Lasting just 90 minutes, the most recent concert by PostClassical Ensemble, presented on Nov. 16 in the Kennedy Center Terrace Theater, was relatively modest: no singers, dancers, actors or narrators; no film screening or live illustration; no gamelan orchestras (that only happened once, in 2019).

The program, titled “Bouncing Off the Walls: Music and Architecture,” was jointly developed by Ángel Gil-Ordóñez, co-founder and music director of the experimentally minded ensemble; Washington Post critic Philip Kennicott; and architect Hany Hassan, director of Beyer Blinder Belle’s Washington, D.C., office.

Courtesy Kennedy Center.

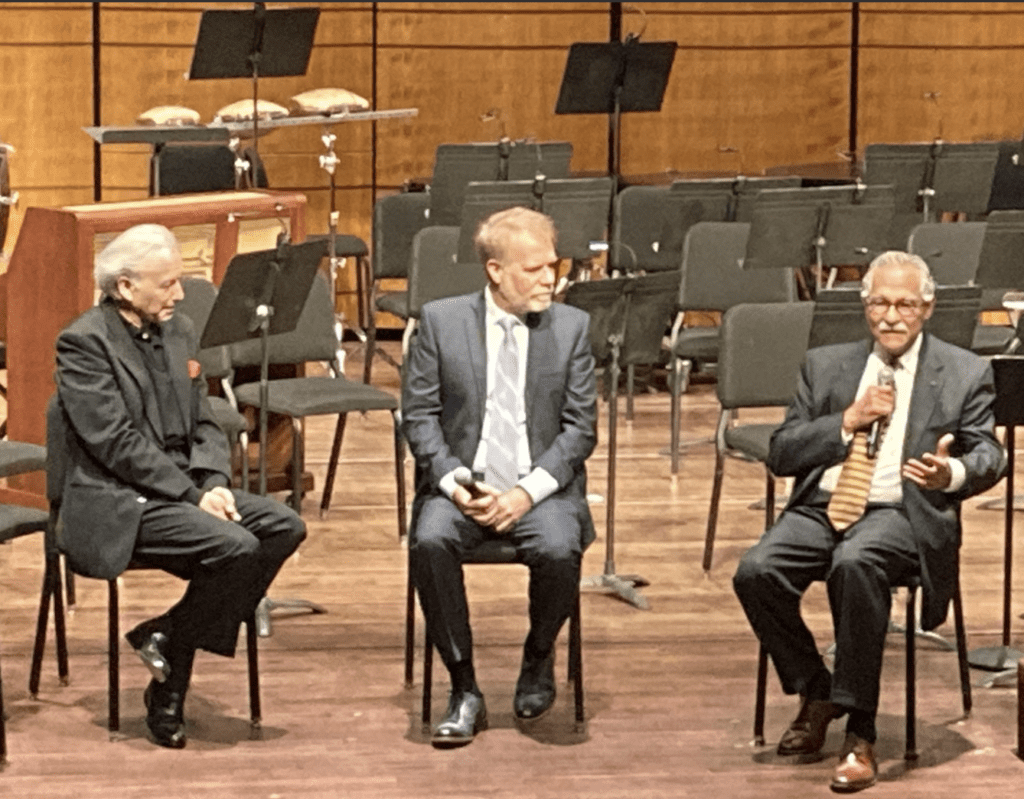

As guest curator, Kennicott offered unscripted commentary from a stool at the left front of the stage. Hassan, who assembled the visual presentation — introductory terminology, slides of pertinent buildings and a video of his rapid sketching of the façade of Venice’s Basilica di San Marco — joined his two collaborators onstage after the performance for a brief Q&A.

To explore the relationship between classical music and architecture, five musical works, chronologically shuffled, had been chosen.

First up was Beethoven’s rarely performed “Consecration of the House” overture, commissioned from the 52-year-old composer for the 1822 reopening of Vienna’s Theater in der Josefstadt. Highlighted points: the piece’s opening chords and diatonic melodic line were comparable to a post (vertical) and lintel (horizontal) framework and certain elements served to test the renovated hall’s reverberation and spatial separation.

The next piece, the antiphonal “Sonata pian’ e forte,” written in the 1590s by Giovanni Gabrieli, either for the Venice basilica or for the city’s Scuola Grade di San Rocco, tested both the Terrace Theater’s acoustics and PostClassical’s brass section, both splendid. Gil-Ordóñez conducted eight brass players, four in each side-balcony, from the stage, no mean feat, while the video played of Hassan hand-drawing the San Marco façade. “I had to draw it in five minutes,” he later exclaimed — enough pressure without having to do so live.

Two beautifully performed movements from Haydn’s Symphony No. 47 followed. A slide of music notation showing how the composer divided the melody of the second movement, Un poco adagio, cantabile, into notes of shorter and shorter duration (quarters, eighths, sixteenths) illustrated Kennicott’s architectural analogies (smaller windows in higher floors, smaller units in a palace’s interior).

Ángel Gil-Ordóñez, Philip Kennicott and Hany Hassan at the post-concert Q&A for PostClassical Ensemble’s “Bouncing Off the Walls.” Photo by Richard Selden.

Written around 1772, the symphony acquired the nickname “The Palindrome” from its third movement, which comprises a minuet and a trio, each with a second half that is the first half played backwards.

Is this musical symmetry comparable to architectural symmetry? Not really, said Kennicott, because it is difficult if not impossible to perceive at a single hearing. Why then did Haydn do it? “Maybe he’s showing off, maybe it’s a parlor trick.” In any case, the less-resonant spaces where music was performed in the 18th century facilitated listeners’ appreciation of compositional complexity.

Since atonalist Anton Webern’s “Five Pieces for Orchestra,” written between 1911 and 1913, is over and done with in five minutes, the reduced ensemble of about 20 players — including performers on harp, mandolin, guitar and two only-when-called-for keyboard instruments, harmonium and celesta — played it twice. In between, to demonstrate how Webern would shatter continuous phrases into fragments assigned to various instruments, concertmaster Netanel Draiblate played a reassembled phrase as a violin solo. As written, the dissonant miniatures brought to mind a forest of twittering birds and insects.

Referencing Arnold Schoenberg’s term Klangfarbenmelodie — sound-color-melody in literal English — Kennicott linked this pared-down musical style, emphasizing different sonic textures, to 1920s modernist architecture, with slides of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s and Lilly Reich’s Barcelona Pavilion of 1929. During the Q&A, Hassan half-jokingly commented that the Barcelona Pavilion never looked so good and Webern’s music never sounded so good as when they were paired.

The concert ended as it began, with an overture, this time from Rossini’s 1829 opera William Tell — “a piece that is so overplayed that nobody plays it anymore,” said Kennicott, channeling Yogi Berra. Citing the book “Spaces Speak, Are You Listening” by Barry Blesser and Linda-Ruth Salter, he introduced the concepts of aural architecture, how the design of buildings is experienced via our ears, and “earcons” (a play on “icons”), defined as “sonic events with enormous emotional, social and sometimes spiritual resonance.”

The “visual analog” to the piece was a slideshow about the 2009 renovation and expansion by Hassan’s firm of the neoclassical District of Columbia Court of Appeals, with the addition of an eye-catching glass-and-steel entrance pavilion.

Opening with a theme played warmly by principal cello Benjamin Capps, which became a cello duet when Benjamin Wensel joined him, the Rossini favorite segued into Looney Tunes territory with delightful solo work by Fatma Daglar on English horn and Kimberly Valerio on flute. It did not take long for the Lone Ranger to arrive. Apart from these “earcons,” the stylistic contrast with the Beethoven overture, composed less than 10 years earlier, was striking (and has little to do with architecture).

“Bouncing Off the Walls” was an opportunity for three knowledgeable and creative individuals with distinct areas of expertise — Gil-Ordóñez, Kennicott and Hassan — to bounce ideas off one another. A side benefit was that the evening’s pleasantly thought-provoking verbal and visual context motivated close listening to the works performed.

Even if the conceptual framework were absent, however, the audience would still have enjoyed hearing this unconventional musical program played by a chamber orchestra that — thanks to its conductor’s sensitivity and the excellence of its member instrumentalists — is unsurpassed.