‘Cassatt at Work’ in Philadelphia

By • June 13, 2024 0 1082

Of the four most accomplished French Impressionists who were women, only Mary Cassatt wasn’t French. Born in 1844 in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now Pittsburgh’s North Side), Cassatt was raised in Philadelphia and Europe. During the Civil War years, she attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where a fellow student was Thomas Eakins.

For most of the 60-year period from 1866 to 1926, when she died, Cassatt lived in France. She studied with Jean-Léon Gérôme and other French painters, had works accepted by the Salon and first showed with the Impressionists in 1879. She participated in three more of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, in 1880, 1881 and 1886.

The owner of 84 works by Cassatt, the Philadelphia Museum of Art treats her like a native daughter. On view at the museum through Sept. 8, “Mary Cassatt at Work” assembles more than 130 of her paintings, pastels and prints in loose subject-matter categories. The exhibition’s title refers to her determination to make art her profession, to her depiction of “the work of women’s lives” and to her artistic process, as revealed in technical studies of the museum’s Cassatt holdings.

A very popular show, “Mary Cassatt at Work” is accessed by timed-entry tickets purchased online and a virtual queue (visitors scan a QR code on arrival).

The main artistic influence on another woman impressionist, Berthe Morisot, three years Cassatt’s senior, was Manet (Morisot posed for him and married his brother). In Cassatt’s case, it was Degas, who visited her Montmartre studio in 1877 to invite her to exhibit with the Impressionists, a clique that already included Morisot, who participated in their first three exhibitions, in 1874, 1876 and 1877.

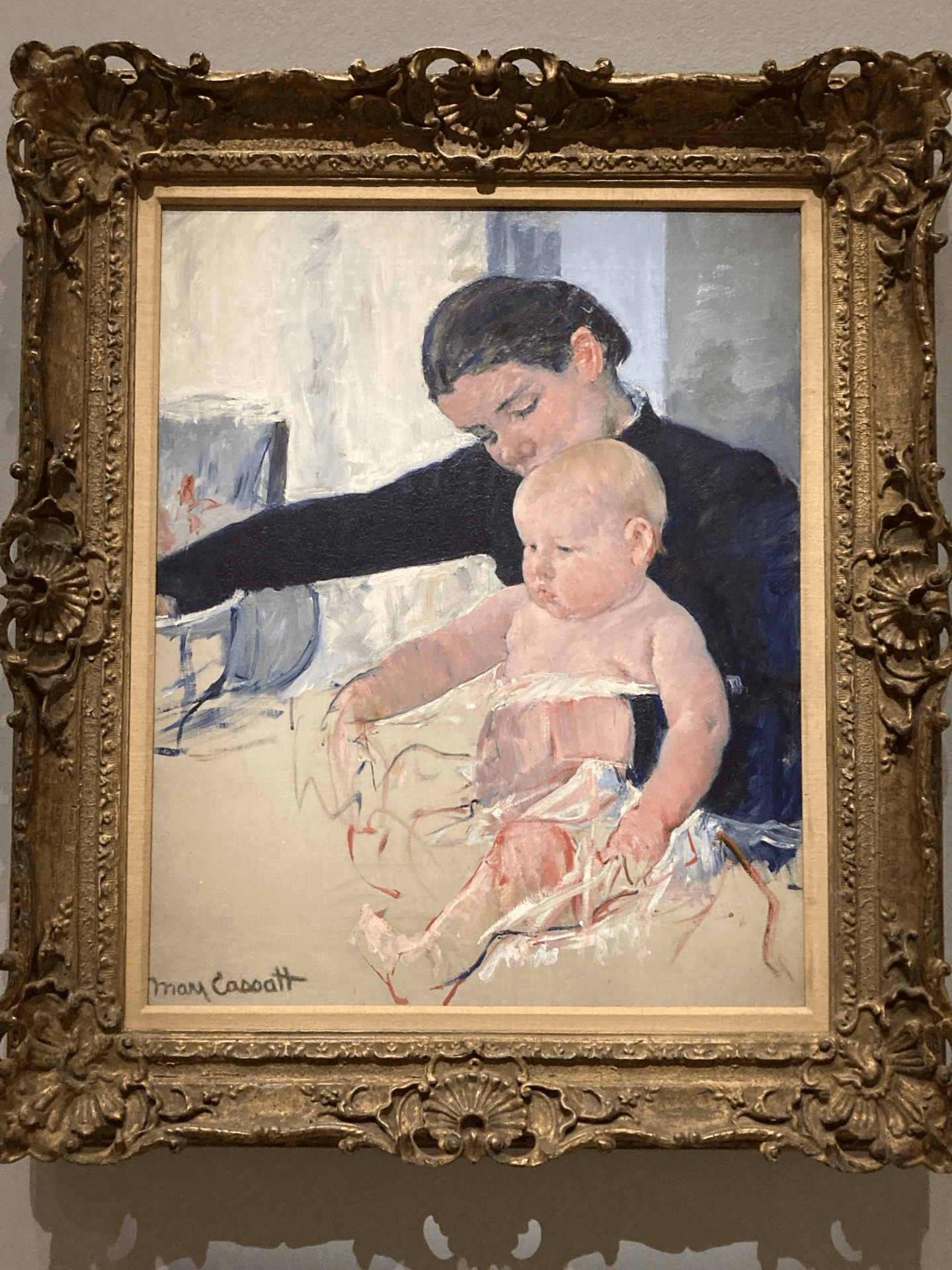

“Bathing the Young Heir,” 1990-91. Mary Cassatt. Photo by Richard Selden.

At the 1879 Impressionist exhibition, their fourth, seven works by Cassatt were hung “in a room of her own” (as the text specifies), including “At the Theater,” which uses pastel and metallic paint to depict a white-gloved woman, her green-and-pink fan spread at center, gazing out from a theater box. Like Morisot’s, Cassatt’s family was upper middle class; she was a frequenter of respectable venues, not the cafés and dance halls (not to mention brothels) that were often her male colleagues’ subjects.

This partially explains why the class-conscious and fastidious Degas, 10 years older, became Cassatt’s mentor, especially from 1877 to 1880, when they more or less worked together (as explored in the National Gallery of Art’s “Degas/Cassatt” exhibition of 2014).

Driven and independent-minded, primarily portraitists and precise in their draftsmanship, the two had a meeting of the minds and, though neither married, not of the bodies (probably). They later drew apart due to Degas’s abandonment of a proposed collaborative journal of prints, “Le Jour et la nuit” — along with his misogyny and growing bitterness and antisemitism — but remained friends up to his death in 1917.

Cassatt’s devotion to printmaking and pastels was largely due to Degas’s example and encouragement. A few of the works on view could be mistaken for works by Degas, for instance, the exquisite oil “Woman at Her Toilette,” painted around 1880.

According to the label for “Little Girl in a Blue Armchair” of 1877-78, loaned by the National Gallery, Degas actually drew in the angled perspective of the room at upper left, adding asymmetric depth to the painting, as if he were Cassatt’s teacher (presumably, she approved).

An accomplishment entirely Cassatt’s own, and a landmark in the narrative of Japanese influence on Impressionism, is a series of color prints made over the winter of 1890-91 known as “The Set of Ten.” A long gallery wall in the exhibition displays all 10, from six public and private collections, several with faint cursive inscriptions by Cassatt.

In 1890, Asian art (and later Art Nouveau) dealer Siegfried Bing exhibited some 700 Japanese woodblock prints — known as ukiyo-e, meaning “images of the floating/passing world” — at the École des Beaux-Arts. Cassatt, who bought a number of them, wrote to Morisot: “I dream of it and don’t think of anything else but color on copper.”

Working with printer Modeste Leroy (a print of Leroy by Marcellin Desboutin hangs nearby), she created 25 sets of 10 striking drypoint-and-aquatint images, each employing three colors, translating c. 1800 geisha scenes to late 19th-century Paris. Also on view in the gallery are associated drawings and “states” — trial proofs — that give insight into her artistic choices and experimentation.

Some of the titles: “In the Omnibus,” Afternoon Tea Party,” “The Fitting,” “The Coiffure” and “Mother’s Kiss.” This last — showing a naked child, arms around the neck of his or her mother, who is seated in a patterned armchair wearing a long dress — is an example of Cassatt’s signature subject.

In a section called Childcare are 28 paintings and prints of babies and children with women. Some seem to reference Madonna-and-Child compositions, but many, as the text emphasizes, represent paid nannies or models posing as paid nannies. Perhaps the outstanding works in this (over)abundant curation are “Bathing the Young Heir” of 1890-91 from a private collection and a series of five drypoint prints from around the same time, hung in a row.

Likewise focusing on the domestic labor of women — in this case, sewing and embroidering — is a gallery called Handwork. Its centerpiece is a work that was in the 1881 Impressionist exhibition, on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Lydia Crocheting in the Garden at Marly,” painted en plein air when the Cassatt family spent the summer at Marly-le-Roi, west of Paris.

The largest gallery of “Mary Cassatt at Work” is a square room with four columns, two of which are encircled by benches. Its light-green color scheme may be meant to suggest a park (if so, it’s a busy one). The left side has the wall title In Public and the right In Private.

Tending to draw the most attention on the left is the splendid “Driving” of 1881 from the PMA’s collection. As described in a letter from Cassatt’s mother to her nephew, displayed in a preceding gallery: “Your Aunt Mary … also painted a picture of your Aunt Lydia & a little niece of Mr. Degas’ and the groom in the cart with Bichette but you can only see the hind quarters of the pony.”

In the final gallery, one finds, with “Little Girl in a Blue Armchair,” another of the exhibition’s most stunning works, the PMA’s “Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son, Robert Kelso Cassatt” of 1884. Cassatt’s brother — in a hiatus from his work with the Pennsylvania Railroad, to which he returned 1899, becoming president — visited Paris with his 11-year-old son. Expertly and freely painted, it is a powerful personal counterpoint to Cassatt’s signature woman-and-child images.

Cassatt, whose eyesight weakened as she aged, wrote in 1915 to her friend Louisine Havemeyer: “Do you think if I have to stop work on account of my eyes I could use my last years as a propagandist?” Both she and Havemeyer, the wife of sugar baron Henry Havemeyer, did much on behalf of two causes: women’s suffrage and the acquiring by American collectors of Impressionist art.

“Mary Cassatt at Work”

Through Sept. 8

Philadelphia Museum of Art

2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

philamuseum.org

215-763-8100