Paula Modersohn-Becker at Neue Galerie New York

By • June 27, 2024 0 1699

The “neue” (pronounced “NOY-uh) in Neue Galerie New York is German for new. Honoring a Vienna gallery of the 1920s and ’30s, the name suits what is still the youngest of the city’s major art museums.

Devoted to art “created in Austria and Germany between 1890 and 1940,” the museum — the vision of Ronald Lauder (son of Estée) and Serge Sabarsky — opened in a Fifth Avenue mansion two blocks from the Met in 2001.

“Portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer I,” aka “The Woman in Gold,” the restituted Klimt that Lauder acquired for a reported $135 million, resides one flight up. On the third floor, visitors to New York this summer can take in an exceptional exhibition, “Paula Modersohn-Becker: Ich Bin Ich / I Am Me.”

Art historian Jill Lloyd organized the show with Jay Clarke, prints and drawings curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it will go on view in October. “Ich Bin Ich” is the first retrospective of Modersohn-Becker’s work in the U.S.; the first in France, at the Musée d’Art moderne, took place just eight years ago.

Over a single decade, Modersohn-Becker’s work passed through Post-Impressionism and foreshadowed German Expressionism. Where she would have ended up is anyone’s guess; she died in 1907, shortly after giving birth at age 31.

The exhibition’s keystone is said to be the first nude self-portrait by a woman, “Self-Portrait on Sixth Wedding (Anniversary) Day” of 1906. Modersohn-Becker stands in a three-quarter pose, looking out with an ambiguous — by no means cheerful — expression, her (pupil-less) eyes and nose slightly enlarged. Behind her, spots of green paint faintly enliven pale yellow wallpaper.

“Otto Sleeping,” 1905-6. Paula Modersohn-Becker.

A white slip covers her otherwise naked body from the hips to above the knees, cut off by the frame. Between her breasts hangs a necklace of amber stones. Almost clawlike, her hands cradle her belly, apparently swollen in pregnancy.

Painted in oil tempera on cardboard, as are many of her paintings, this is an even odder work than it seems. A notation of when she completed it at lower right is signed “P.B.,” omitting the M. The date was her fifth anniversary, not her sixth. And she did not become pregnant until the following year, after reconciling with her husband and returning from Paris, where she was in the midst of a stylistic and psychological breakthrough. (Was this the depicted “pregnancy”?)

Paula Becker met plein-air landscape painter Otto Modersohn in the summer of 1897 at an artist colony in Worpswede, a soggy village outside of Bremen. She had studied art earlier near London, then in Bremen — her hometown throughout her teens —and would later study in Berlin and Paris. In the fall of 1898, she returned to Worpswede for a longer period, during which she made the 14 charcoal drawings displayed in the first, apricot-colored room at the Neue.

Though these are “academic” life drawings, they are unusually gripping. Half are quite large, including two life-size standing nudes, a man and a woman, in profile. Drawings of a farmer and his wife murkily emerge from their dark backgrounds. Modersohn-Becker (still Becker at that point) combined three drawings of nude girls on a single sheet; the text notes that she portrayed them and others in the exhibition with “no overt sexualization,” unlike German Expressionists such as Erich Heckel and Ernst Kirchner in the decades to come.

In 1900, after visiting the Paris Exposition Universelle, she was back in Worpswede, where the activity centered on artist Heinrich Vogeler’s Barkenhof (Birch Tree Cottage). She and Modersohn became engaged that year, marrying in 1901.

Paintings with birch trees, with and without figures, fill the mansion’s music room (recorded period music plays), with walls of turquoise above stained-wood wainscoting. Trees and people alike are individualized, yet somehow unreal, as if possessed. In the center of the long wall is “Girl Blowing a Flute in the Birch Forest” of 1905. Over the mantelpiece against the opposite wall is “Girl Sitting Between Trees in a Meadow of Blooming Anemones” of c. 1901; on the far wall, in between landscapes: “Old Woman From the Poorhouse Sitting in the Garden” of 1905.

On a side wall are small portraits of poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who met Modersohn-Becker in Worpswede and became a confidant; sculptor Clara Westhoff, her friend and fellow student, who married Rilke in 1901 (her bust of Modersohn-Becker is in the drawings gallery); and her husband (“Otto Sleeping” of 1905-6).

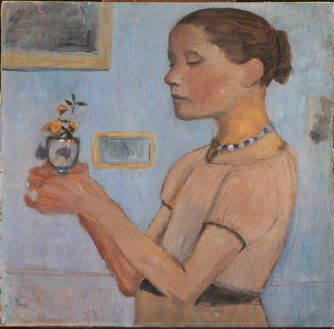

Of the remaining works, one of the most intriguing is “Young Girl With Yellow Flowers in a Glass” of 1902. With brown hair in a tight bun, the subject, in profile, meditating or praying or simply still, holds out a vase with blue and white highlights like those of her necklace. Three indistinct artworks, cropped by the frame, hang on light blue wallpaper, through which the surface of the cardboard peeks.

In the narrow gallery called The Intimate Eye are many small head and head-and-chest portraits. Noting that “Their scale and mood relate to Roman-Egyptian funerary portraits that Modersohn-Becker viewed in the Louvre,” the text quotes Modersohn-Becker, who wrote of those works, known as Fayum or “mummy” portraits, painted in a wax medium beginning in the late first century B.C.: “Brow, eyes, mouth, nose, cheeks, chin, that is all. It sounds so simple and yet it’s so very, very much.” Hers also recall van Gogh in their use of thick outlines and backgrounds of one or two solid colors.

Unmissable in the final, light blue, gallery, where the sixth-anniversary work hangs, is the large, powerfully exposed and unadorned “Reclining Mother With Child II” of 1906.

One also finds a group of nude girls and women, one suckling an infant, in a dark, “exotic” mode, making use of such painted props as thick foliage, poppies, oranges, “primitive” jewelry and a stork. These were likely inspired by Gauguin, as well as by tribal art that Modersohn-Becker saw, the text notes, in the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris (where Picasso came face-to-face with African masks).

And there are two groupings of clothed self-portraits. Left of the entrance, three show the artist from the waist up, with a bowl and a glass, with a rose and with a blue glass. In two, she wears a sunhat outdoors. Right of the entrance is a lineup of four self-portraits from the chest up. Three have, again, what might be called totems: a lemon, a camellia branch and a pair of strange, stylized flowers. This enigmatic “Self-Portrait With Two Flowers in Her Raised Left Hand” of 1907 was her last. It’s been suggested that the blooms represent Modersohn-Becker and her child-to-be or her conjoined identity as married woman and artist.

Finally, there are four still lifes, mostly of fruit: one like a 17th-century Dutch painting, two resembling those of Paul Cezanne and one, “Still Life With Clay Jug, Peonies and Oranges” of 1901, in a starker, more modern style, with a tablecloth of thick white visible brushstrokes. Modersohn-Becker’s experimentation and rapid development, tragically cut short, is clear.

The year after her death, Rilke wrote “Requiem for a Friend,” a long poem addressed to Modersohn-Becker. An excerpt, in Stephen Mitchell’s translation:

Women too, you saw, were fruits; and

children, moulded

from inside, into the shapes of their

existence.

And at last, you saw yourself as a fruit,

you stepped

out of your clothes and brought your

naked body

before the mirror, you let yourself inside

down to your gaze; which stayed in front,

immense,

and didn’t say, I am that; no: This is.

“Paula Modersohn-Becker: Ich Bin Ich / I Am Me”

Through Sept. 9

1048 Fifth Avenue (at 86th Street)

212-628-6200