‘The Kite Runner’ Pulls at the Heart at the Kennedy Center

By • June 27, 2024 0 1371

By Hailey Wharram

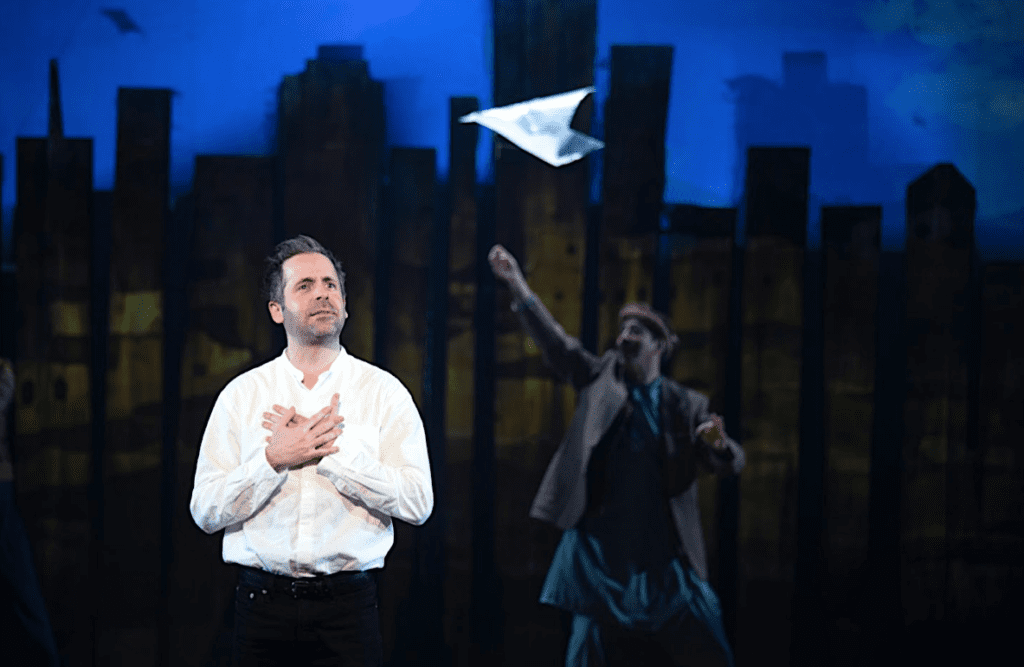

White paper kites pepper an azure Kabul skyline as Amir (Ramzi Khalaf) delivers the searing opening line of “The Kite Runner”: “I became what I am today at the age of 12.” The lines that follow pack a similar gut-punch, foreshadowing the poignant yet devastating tale to come: “It’s wrong what they say about the past, I’ve learned, about how you can bury it. Because the past claws its way out.”

Directed by Giles Croft, “The Kite Runner,” playwright Matthew Spangler’s stage adaptation of Khaled Hosseini’s best-selling 2003 novel, is running at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater through June 30. Washington, D.C. marks the final stop on the show’s national tour which began in April 2024 at the Hammer Theatre in San Jose, California, the same venue where the show originally premiered in 2009.

The show follows the life of Amir—specifically his complicated relationships with childhood best friend Hassan (Shahzeb Zahid Hussain) and his loving yet stern father Baba (Haythem Noor)—beginning with his adolescence in Kabul, Afghanistan, in the 1970s. Hassan and his father Ali (Hassan Nazari-Robati) work as servants for Baba and Amir’s wealthy family. While Amir and Baba are Pashtuns, Sunni Muslims belonging to the majority ethnic group within Afghanistan, Hassan and Ali are Hazaras, Shi’a Muslims who face persistent, brutal discrimination within the nation. Amir and Hassan grow up inseparable in spite of their economic, ethnic and religious differences. However, one fateful day after they compete together in a local kite fight, Amir’s insurmountable cowardice drives a sharp, irreparable wedge between them: Hassan is brutally attacked as Amir watches in silence. After grappling with his gnawing bystander’s guilt for years to come, Amir becomes determined to atone for the sins of his youth and to make it up to Hassan—the gentle, fiercely loyal boy whose first word was Amir’s name.

The complex lead role of Amir is both technically and emotionally demanding. For starters, because Amir’s younger and older selves are played by the same actor (an effective creative choice which accurately reflects the character’s emotional stagnation on account of his spinelessness), the actor is on-stage throughout the entire performance. Furthermore, beyond pure stamina, Amir necessitates a performer capable of helping us feel the depths of every heartbreaking narrative twist and empathize with him even when his choices leave us horrified. Thankfully, the role could not be in safer hands than with Ramzi Khalaf; the audience hung dutifully upon his every word, lamenting and laughing right alongside him from start to finish.

“Amir is deeply flawed; he can be maddening, and his cowardice and hypocrisy at times border on appalling,” author Khaled Hosseini wrote for LitHub.com last year in honor of the book’s 20th anniversary. “But I think he is always recognizably human. He walks the world painfully aware of his faults and failures. They haunt him through adolescence and into adulthood. He knows that a more noble version of himself lies somewhere ahead, but the reach is far, the path treacherous, and to get there he must summon the courage he disastrously lacked as a child. Despite our aversion to his actions, we root for him, perhaps because we find fragments of ourselves reflected in him: We all know we fall short; we all want to walk in the shoes of that more noble self.”

Like Amir, author Khaled Hosseini was born in Kabul and moved to California in the early 1980s. In 2001, the same year in which the United States invaded Afghanistan following the attacks of September 11, Hosseini penned the majority of his debut novel, “The Kite Runner,” across a series of early mornings before attending work as a physician. The novel was published in May 2003, but did not capture much public attention until the fall of 2004, after which it spent a whopping 101 weeks on the NYT bestseller list. In 2007, Marc Forster directed a film of the same name based off of Hosseini’s remarkable book, and two years after that, Spangler brought Amir and Hassan’s story to the stage. Even over 20 years later, “The Kite Runner” continues to move readers and theatergoers alike all over the world.

While “The Kite Runner” does not shy away from the violent conflicts of Afghanistan’s history, the show simultaneously takes great care in depicting the rich vibrance of Afghan culture. In addition to spotlighting the celebrated Afghan tradition of kite running, actors frequently speak in Farsi on stage without catering to English-speaking audiences by offering translation. Additionally, during a pivotal wedding scene, the men jubilantly perform the Afghan national dance—the Attan—in a much-needed moment of levity amidst a somber second act.

“I am most grateful that ‘The Kite Runner’ has changed the way readers around the world see Afghanistan, offering those unfamiliar with the country a more human, nuanced, and textured portrait,” Hosseini wrote. “For so long, stories about Afghanistan revolved around war, displacement, hunger, extremism, and the maltreatment of women and girls. Sadly, many of those stories remain relevant today, but they are not the only truths of the place.”

“The Kite Runner” has a runtime of 2 hours and 30 minutes, including one intermission. Tickets can be purchased here.