‘Little Beasts’ at the National Gallery

By • July 15, 2025 0 723

By Sheila Wickouski

Delightful and insightful, “Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World,” at the National Gallery of Art through Nov. 2, is a convergence of art and science. The exhibition, a collaboration with the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, displays prints, drawings and paintings alongside natural history specimens and taxidermy, showing how artists and naturalists in 16th– and 17th-century Holland viewed bugs, butterflies, birds and other “beestjes” (little beasts).

Theirs was an era of scientific technology, trade and colonial expansion — all leading to the study of previously unknown or overlooked species in great detail.

The opening gallery, Joris Hoefnagel and Early Natural History 1500-1600, features one of the NGA’s treasures: Hoefnagel’s “Four Elements.” This series of 270 watercolors, bound into four books, was originally in the private collection of Emperor Rudolf II of Austria. Seldom on view due to their sensitivity to light, the pages will be turned three times during the exhibition’s run.

“Terra (earth)” features porcupines, lizards, a guinea pig and a caterpillar. “Aier (air)” depicts a cormorant, herons, bats and owls. “Aqua (water)” holds a flying swallow, a sperm whale squad and crabs. “Ignis (fire)” includes dragonflies, beetles and moths.

A watercolor that was once removed from the set and is now in a private collection, Hoefnagel’s “Turkey and Turkey Hen with a Finch between a Pumpkin and a Bush of Red Berries” of c. 1575/1590s, is on display for closer inspection.

The surrounding gallery walls are filled with animal illustrations paired with specimens. Jacopo Ligozzi’s “A Woodchuck or Marmot with a Branch of Plums” of 1605 is accompanied by “Marmota manox” from an NMNH collection.

The second gallery, Animal Prints 1580-1650, does the same with engravings and etchings. The litany of animals includes a Eurasian hoopoe (a crested bird), an elephant beetle, a musk beetle, a hummingbird hawk-moth and a mantis shrimp. An etching by Teodoro Filippo di Liagno, “Skeleton of a Goose,” from the series “Animal Skeletons” of 1620-21, is an example of the scientific illustration of the time.

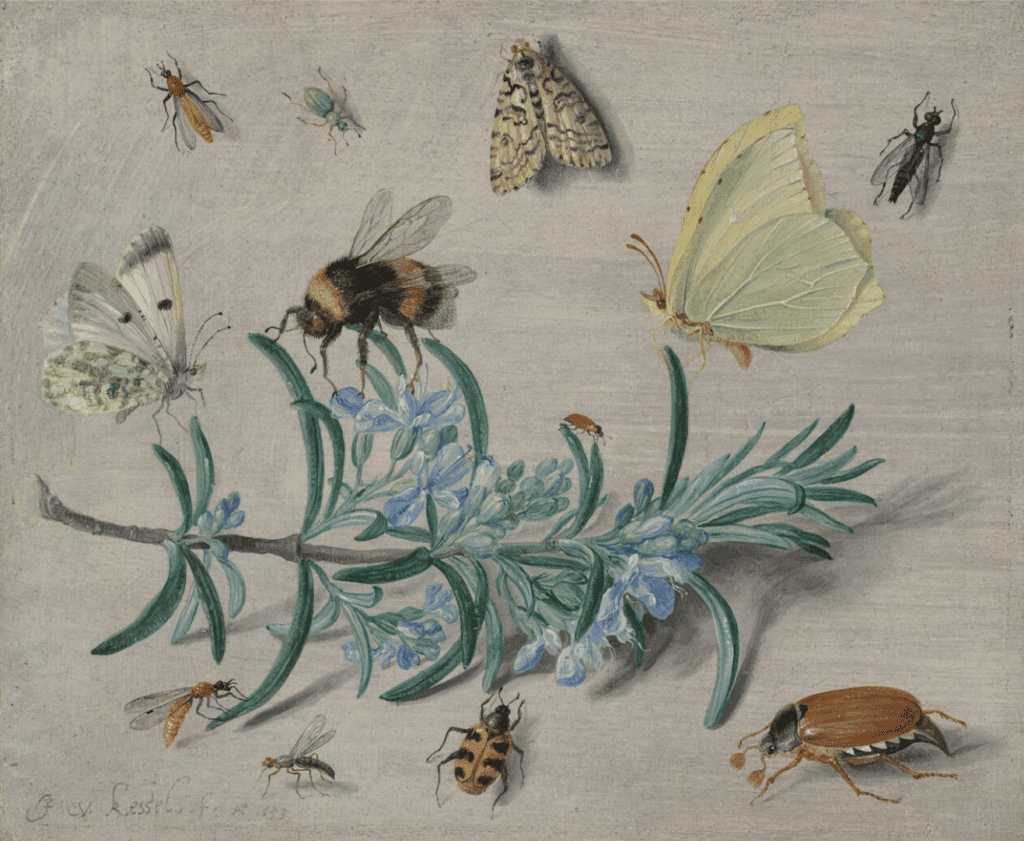

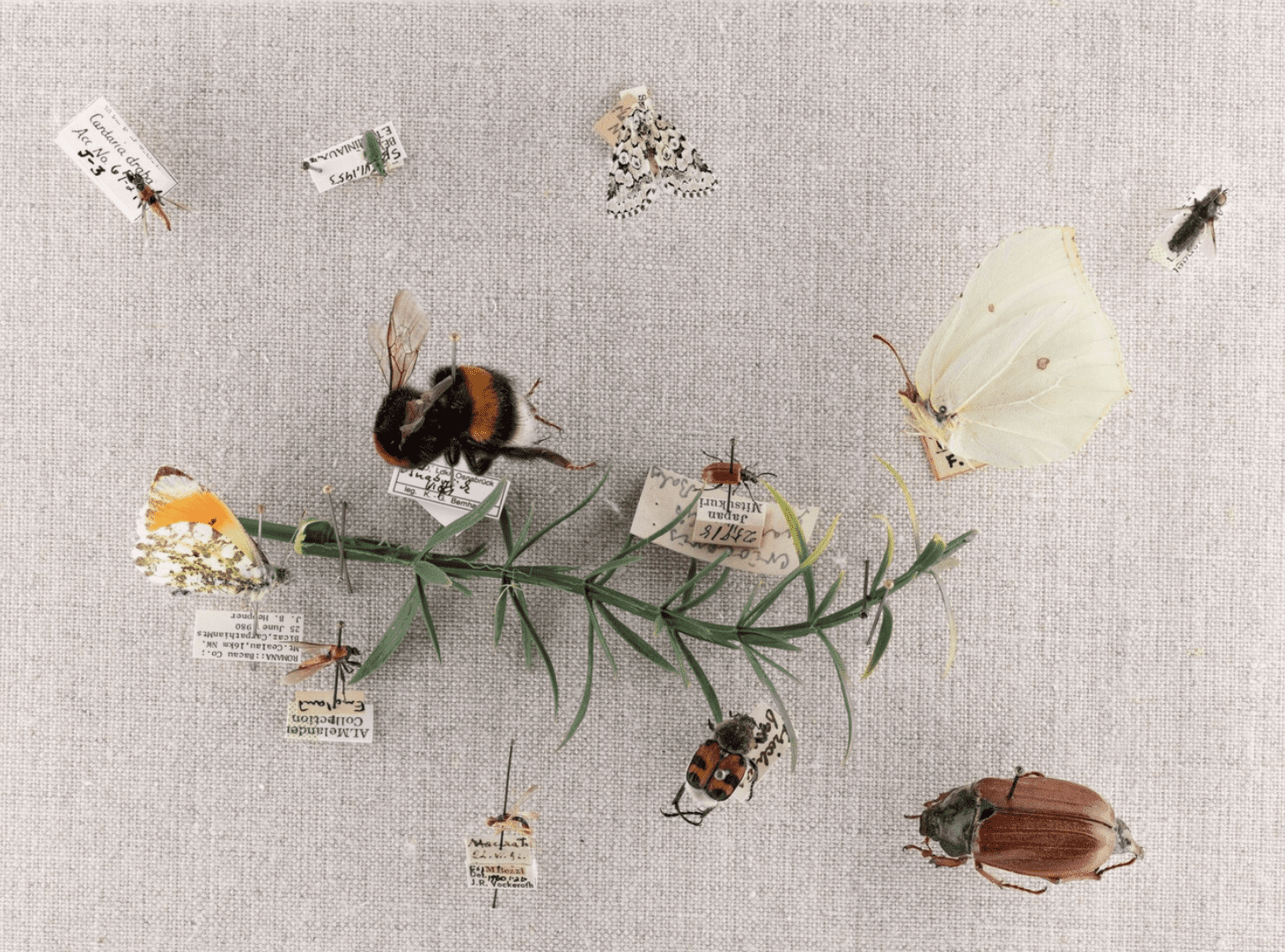

The final gallery, Jan van Kessel’s Ecosystem 1650-1670, is a celebration of van Kessel’s paintings. Here are prints, books and a sampling of the creatures, such as seashells, insects, a parrot, a peacock, a porcupine and a macaque, that inspired him. NMNH scientists have identified every insect in his microscopic works, such as “Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary” of 1653, to create a custom tableau. An interactive kiosk recreates the decorative art cabinets in which van Kessel’s postcard-sized works were usually displayed.

Unknown National Museum of Natural History’s recreation of Jan van Kessel the Elder’s Insects and a Sprig of Rosemary Loan courtesy of National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution From the Department of Entomology Collections, Smithsonian Institution. Photo by James Di Loreto.

Here also appears a rare subject in the exhibition: the image of man himself. Jan van Kessel’s “Noah’s Family Assembling Animals before the Ark” of c. 1660 includes humans in the midst of a wide array of exotic animals. This amazing variety of imported creatures includes birds from the New World, such as turkeys, parrots and the rare purple gallinule, along with African ostriches and porcupines — the latter’s incredibly long quills raised in defense — amid lions and leopards. In the center, a dapple-gray horse poses, part of the showcase of royal pets. The biblical story thus expanded is a fitting summary to the exhibition.

As a side note, Jan van Kessel the Elder was the grandson of Jan Brueghel the Elder, who had earlier (in 1613) painted “The Entry of the Animals into Noah’s Ark,” now in the Getty collection. And yes — the turkey in van Kessel’s painting was indeed a living animal, one of many exotics that roamed the royal gardens.

A 43-minute video created for the exhibition by Dario Robleto, “Until We Are Forged: Hymns for the Elements,” is both a meditation and a demonstration. Through site-specific filming, historical footage, animations and an original score, the piece links the work of Hoefnagel and van Kessel to the efforts of modern-day NGA conservators and image scientists to preserve these works for future generations. The video starts on the hour in the exhibition’s final gallery.

Additional works by Robleto are in Gallery 50 along with 17th-century Dutch paintings. “Dario Robleto: Small Crafts on Sisyphean Seas” features objects of wonder which he created by combining sparkling synthetic materials and natural objects like seashells and butterfly wings into forms that suggest plants and animals. Robleto was inspired by the Golden Record, the gold-plated phonograph disk sent aboard the Voyager spacecrafts in 1977, imagining this sculpture as his own gift to extraterrestrials.

Finally, on view through Oct. 31 in the East Building’s Library Atrium, as a complement to the “Little Beasts” exhibition in the West Building, is “In the Library: Animal Illustration in Europe, 1550-1750,” a display of 40 rare books, scientific drawings, illustrated fables and drawing manuals from the 16th to 18th centuries.