In the NGA’s Gallery 22: Corcoran Watercolors

By • September 24, 2025 0 653

Along with the National Gallery of Art’s two feature presentations this fall — “Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955-1985,” which opened on Sept. 21, and “The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art,” opening on Oct. 18 — now showing in the West Building is what movie theaters used to call a short subject: “American Landscapes in Watercolor from the Corcoran Collection.”

Curated by Amy Johnston, associate curator of collections in the department of Old Master drawings, the exhibition of some 30 works is on view through Feb. 1 in Gallery 22 on the ground floor, a few steps down from the 7th Street NW side entrance. Two linked rectangular rooms often overlooked, the gallery typically contains focused displays of prints, drawings and photographs. Closely examining a work, or admiring several from the sole bench, one feels like a connoisseur.

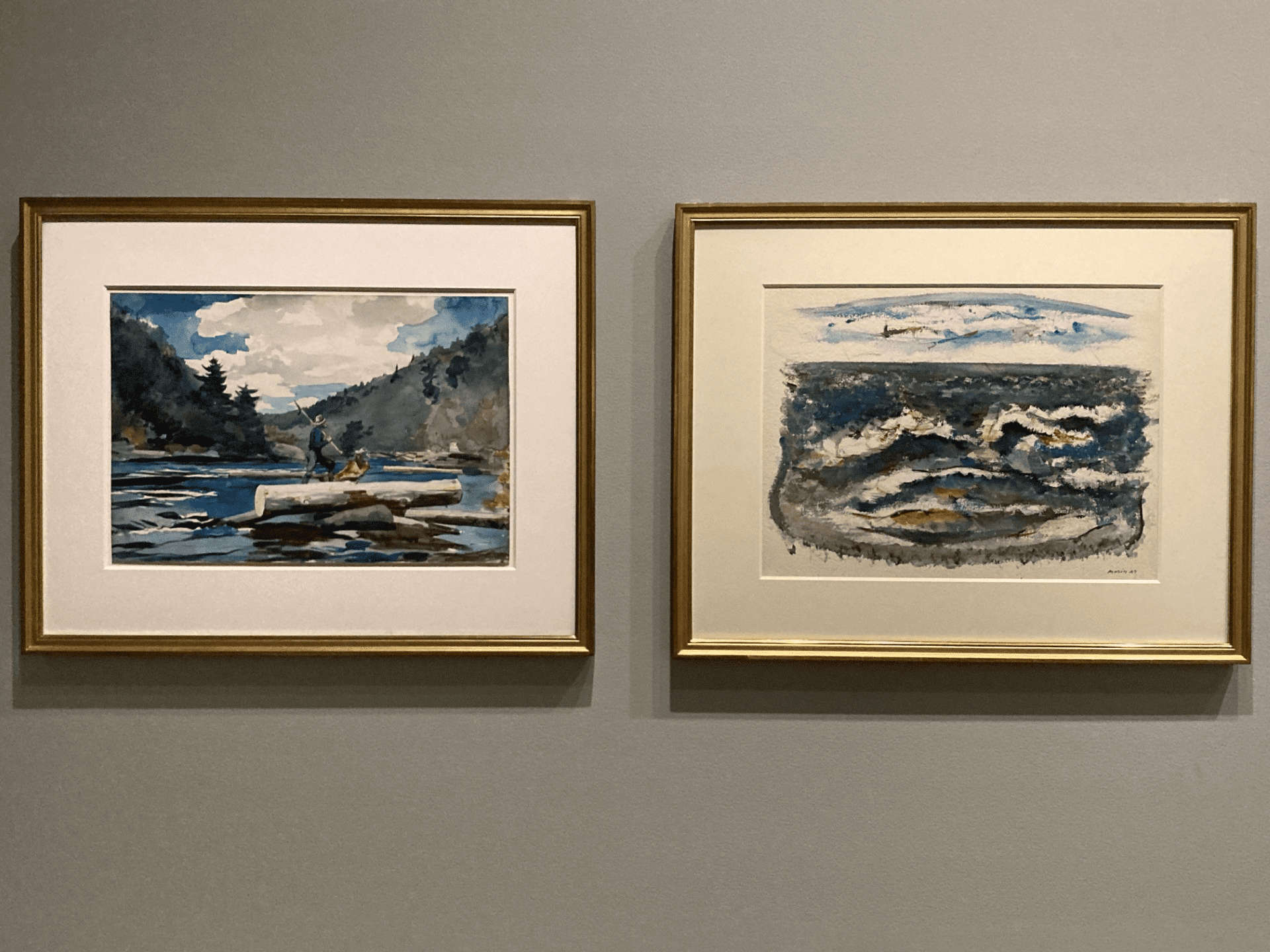

Left: “Hudson River, Logging,” 1891-92. Winslow Homer. Right: “Flint Isle, Maine — No. 1,” 1947. John Marin. Photo by Richard Selden.

The exhibition’s title pretty much sums things up. Landscapes from the Washington, D.C., region; from New England and New York; and from the Far West are depicted, though not always by Americans. In addition to watercolor, the artists employed graphite (pencil), gouache (opaque water-based pigment), ink, pastel and colored oil (Irvine) and rubber stamping (Steinberg). With a few exceptions, the works are from the 9,000-plus items acquired from the Corcoran Gallery of Art after its 2014 closure.

A good place to start is the rear room’s far right corner, where works by two of the greatest American watercolorists (and oil painters) hang side by side: Winslow Homer’s “Hudson River, Logging” of 1891-92 and John Marin’s “Flint Island, Maine – No. 1” of 1947. Though his airy logging scene is fully representational, Homer’s virtuosity with the medium — which involves a back-and-forth with the paper and rarely allows for rethinking — was criticized in his day for looseness. Marin’s balance of expressiveness and control is even more extreme; a firm horizon line divides his sketchy, fragmented sea and sky (Homer’s “horizon” is a cloud-filled V formed by mountain slopes). Leaving much of the sky, most of the breaking waves and the sheet’s border untouched, Marin gives the white paper a leading role.

On the far back wall is the largest work, “South West Point, Conanicut,” signed 1879 by Philadelphia-born William Trost Richards. It’s hard to imagine a scene this spectacular in Rhode Island (no offense). “He intended this work to rival the appearance of an oil painting,” the label notes, using “watercolor and gouache on fibrous brown paper.” Three smaller works by Richards, who became obsessed with painting the Atlantic coast — like Homer, though more meticulously — are on an adjacent wall.

“The Afterglow, Grand Canyon, Arizona,” c. 1904. Lucien Whiting Powell. Photo by Richard Selden.

Also in that room are works unlike any of the others. Romanian American Saul Steinberg, known for his surreal New Yorker art, is represented by “Three Landscapes” of 1974 (in a single frame), in which tiny silhouetted figures appear lost and/or awestruck amid bleak vistas. Two circa-1927 pieces, “Impression of the Plains” and “Winter,” by Wilson Irvine, an Illinois-born member of the Lyme, Connecticut, art colony, are likewise unworldly, though whirlwinds of color. Per the label, Irvine’s experimental technique involved marbling the paper by placing it face down in a tray of water with stirred-up drops of colored oil, then using touches of watercolor and pastel “to define figures and to generate a sense of landscape and sky.”

The exhibition begins with four 19th-century preparatory drawings by two English artists, Walter Paris and William Russell Birch, and one American, Thomas Doughty, for larger works in the topographical/Picturesque tradition: “David Burns’s Cottage and the Washington Monument,” “Falls of the Potomac,” “View from the Springhouse at Echo” and “Harpers Ferry from Below.” In the far corner are two beautifully painted watercolors by Dora Louise Murdoch, born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1857, showing the Ellen Biddle Shipman-designed gardens of the James Parmelee estate around 1920; part of those gardens was preserved as the Tregaron Conservancy in Cleveland Park.

Also in the front room are the Western scenes, notably: “Half Dome and Royal Arches, Yosemite, from Glacier Point,” circa 1870, by Samuel Colman, born in Portland, Maine, in 1832; and “The Afterglow, Grand Canyon, Arizona,” circa 1904, by Lucien Whiting Powell, born in Upperville, Virginia, in 1846. Three moodily thrilling late 20th-century works by Los Angeles-born artist Donald Holden provide a striking counterpoint: “Ontario Sunset” of 1988 and “Mendocino Moonlight IV” and “Yellowstone Fire XIX” of 1991. The label quotes Holden: “No, I never actually saw the Yellowstone fire. All I saw were the blackened slopes and millions of charred tree trunks in 1989, the year after the fire. I watched hours of TV footage and made page after page of rapid drawings as if I were on the spot.”

A final highlight: “Winter Shadows,” a startlingly fresh work in watercolor and ink painted around 1960 by D.C.’s own Alma Thomas, whose vibrant patterned abstractions are the subject of the exhibition “Composing Color,” which closed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in August of 2024 and is on tour through 2027.