Treasures and Tigers of Korean Art

By • January 15, 2026 0 513

The year after the death of Lee Kun-hee in 2020, the Samsung Group chairman’s family donated more than 23,000 works of Korean art from his collection — begun by his father, Samsung founder Lee Byung-chul — to the South Korean nation.

Having toured the country’s museums, some 200 of the choicest pieces, and others from the Leeum Museum of Art in Seoul, are on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art in the exhibition “Korean Treasures: Collected, Cherished, Shared.”

The show was able to open as planned on Nov. 15, three days after the federal shutdown ended, and is due to close on Feb. 1. Next stops: the Art Institute of Chicago in March and the British Museum in September.

Wooden stand for a Buddhist ritual drum, 19th century. National Museum of Korea. Photo by Richard Selden.

In 10 thematic galleries on two levels, “Korean Treasures,” spanning 1,500 years (Chicago rounded up to 2,000), displays: Buddhist ritual objects, altar paintings and sacred texts; ceramics, furniture, books, manuscripts and scholars’ possessions; and paintings on scrolls and folding screens and by 20th-century artists. Here are three of the most stunning:

- A gilt bronze foliated basin from the 11th or 12th century, used to bathe a sculpture of the baby Buddha on his birthday (May 24 this year, though the date varies by country). Its interior shows the Amitabha Buddha, the focus of worship in Pure Land Buddhism, encircled by the eight Sanskrit characters of his mantra.

- From a Buddhist temple pavilion, a 19th-century painted wooden stand for a ritual drum (without the drum) in the shape of a roaring lion with a lotus-shaped base on its back.

- A gourd-shaped celadon ewer from the 13th century, inlayed with red and white slip (liquid clay) and decorated with lotus petals. Around its neck, figures of boys hold lotuses; a frog on the handle was linked to the lid by a now-missing string. Among the dozen pieces in the show designated national treasures by the Korean government, the ewer, from the Leeum Museum, is one of three known to exist; another is part of the National Museum of Asian Art’s permanent holdings of nearly 800 Korean objects.

A label in the ceramics gallery at the bottom of the exhibition’s staircase quotes Lee Byung-chul in 1976: “Among the various items, the Goryeo celadons hold a special place in my heart.”

Called cheongja or Goryeo ware — for the dynasty that unified the peninsula, ruling from Gaegyeong (now Kaesong in North Korea) from 918 to 1392 — Korean celadon pottery, produced for royal family members and the aristocracy, is highly regarded for its pale green glaze, known as bisaek, and delicate slip-inlay technique, known as sanggam, typically depicting lotuses, willows, clouds, ducks and cranes.

(The word celadon apparently comes from the name of a shepherd, Céladon, who wore grayish-green ribbons and a matching coat, in “L’Astrée,” a 17th-century French novel.)

A row of bowls illustrates a centuries-long stylistic evolution. “The Goryeo dynasty’s refined celadon gave way to the bold designs of buncheong ware, and later, to the serene white porcelain that reflected Neo-Confucian ideals of purity and simplicity,” explains a label.

The Joseon dynasty, which overthrew Goryeo — the source of the name Korea — ruled from 1392 to 1910 (when Korea became a colony of the Japanese Empire), moving the capital to Hanseong, modern-day Seoul. Buddhism was repressed, giving opportunity not only to Neo-Confucianism but, eventually, to Christianity.

Another factor: the Imjin War of the 1590s, two brutal invasions by Japanese forces under Chancellor of the Realm Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The Japanese withdrew in 1598 following Hideyoshi’s death and Ming China’s aid to Korea. The removal of master Korean potters to Japan after the war is credited with initiating Japanese porcelain production.

“Korean Treasures,” notes the museum, “opens and closes with a reflection on the practice of collecting in Korea, drawing inspiration from the tradition of chaekgado — vibrant painted screens depicting scholarly books and treasured objects.”

Upstairs is one of those trompe-l’oeil folding screens, from the 19th century. At the downstairs entrance, “Chaekgado Reimagined” is a large bookcase “presenting a dense array of art and artifacts from the renowned Lee Kun-Hee Collection.” Information about each of the objects on the shelves can be called up on a touch-screen kiosk. This “virtual cabinet of curiosities” is also available on the museum’s website.

A lower-level gallery displays the most recent works in the exhibition: around a dozen modern and contemporary paintings, including “Echo 19-11-73, #307” of 1973 by Kim Whanki (1913-1974) and “Shamanism 3” of 1980 by Park Saengkwang (1904-1985). (As with the Lees of Samsung, the artists’ surnames, Kim and Park, come first.)

Park’s “Shamanism” series brings the Expressionist paintings of Max Beckmann to mind with their fragmented and overlapping, semi-representational imagery. These works reference Korea’s traditional “five-colors painting” of white, black, blue, yellow and red, known as obangsaek.

Celadon ewer, 13th century. Leeum Museum of Art. Photo by Richard Selden.

Kim, who like Park trained in Japan, returned to Korea, then spent time in Paris and, beginning in 1963, New York, where he died. Influenced by Korean aesthetic principles as well as the work of New York painters such as Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko, he created remarkable abstract works called chommyonjonhwa, meaning “all-over canvas dot paintings.”

Kim is represented in an upstairs gallery by his 1974 painting “La Lune (Symphonie en Blanc),” from the Leeum Museum. Nearby is an 18th-century porcelain storage jar, the top and bottom halves of which were made separately on a potter’s wheel, then joined. A label notes that images of these globular containers “frequently appear in twentieth-century Korean oil paintings”; other examples are on view. As for Kim, “the textbook I used were these jars.”

The exhibition’s lead curator is Yeonsoo Chee, the Art Institute of Chicago’s Korea Foundation associate curator of Korean art. Its presentation at the National Museum of Asian Art was organized by Carol Huh, associate curator of contemporary Asian art; Keith Wilson, June and Simon K.C. Li curator of ancient Chinese art; and Sunwoo Hwang, who became the museum’s inaugural Korea Foundation assistant curator of Korean Art and Culture in 2024.

Entering the dried fish and produce trade in 1938, presenting corporate sponsor Samsung, meaning “three stars,” is now Korea’s largest chaebol (conglomerate). The current chairman is D.C.-born Jay Y. Lee (Lee Jae-yong), 57, grandson of the founder.

Next Thursday and Friday, a free symposium on Korean art collecting will be presented by the Freer Research Center in the museum’s Meyer Auditorium. On Jan. 22, Youngna Kim, professor emerita at Seoul National University, will give the keynote at 6 p.m. There is a livestream option for the talks on Jan. 23 from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Speakers’ affiliations include: the Academy of Korean Studies, Chuncheon National Museum, the Gyeonggi Province Cultural Heritage Committee, Myongji University, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Korea), Sungkyunkwan University and the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.

A second, much smaller and quite different exhibition of Korean art, “Charm of Seoul, Minhwa: Wishes in Korean Folk Painting,” is on view through Feb. 20 at D.C.’s Korean Cultural Center.

The show features traditional and contemporary minhwa paintings, painted ceramics and other pieces from the Seoul Museum of History, along with a digital-media folding screen from the National Museum of Korea.

Per the center, minhwa, which means “painting of the people,” refers to “the traditional folk paintings which evolved alongside Seoul’s own history and culture during the heights of the late Joseon Dynasty era leading up to the 20th century.”

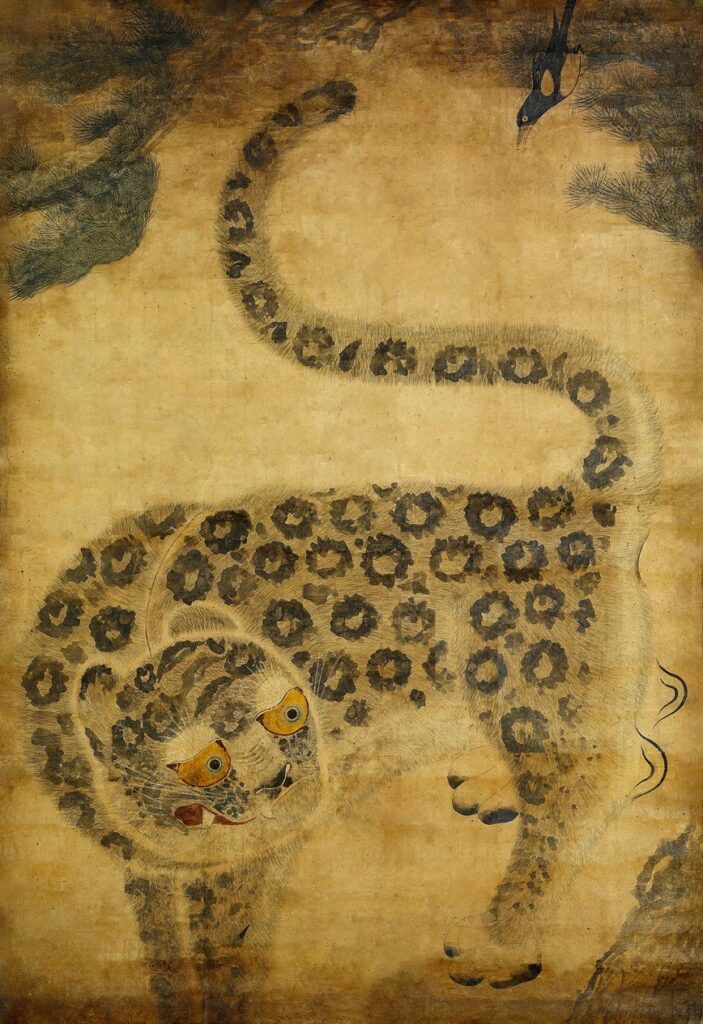

Visitors who have seen the animated film “KPop Demon Hunters” will recognize the genre known as hojakdo (tiger magpie painting) and kkachi horangi (magpie tiger) as the source of the characters Derpy and Sussie. Traditionally painted as “protection from diseases and malicious intent,” according to the text, these works were also meant to satirize Joseon society, with the dim-witted tiger representing the authorities and aristocrats and the magpie the common people.

Korean Treasures: Collected, Cherished, Shared

Through Feb. 1

National Museum of Asian Art, 1050 Independence Ave. SW

Charm of Seoul, Minhwa: Wishes in Korean Folk Painting

Through Feb. 20

Korean Cultural Center, 2370 Massachusetts Ave. NW