The Art of Japan At The Textile Museum and the National Gallery

By • May 3, 2012 0 2076

When taking on the art of an unfamiliar cultural tradition, it’s difficult to know where to start. There are immediately questions—namely, Do I understand what I am looking at? The aesthetic terrain, symbolism and subject matter are foreign, often incongruous to our own knowledge. For instance, as far as everyone in America and Europe is concerned, a hexagram is synonymous with the Star of David (the Jewish Star). However, in ancient Indic lore, the hexagram was a symbol of creation, the overlapping triangles representing “the divine union of male and female.”

When dealing with a culture as deeply rooted, multifaceted and intricate as Japan’s, there is almost no way to take it all in. Japan has a cultural and religious system of symbols and an artistic tradition as unique and fascinating as any in the world, and to know it would require years of time and effort. However, in the same way Picasso found revelation in African tribal masks for their raw aesthetic radiance, it is sometimes enough to admire the beauty and facility of cross-cultural artisanship.

Right now, The Textile Museum and the National Gallery of Art are hosting monumental exhibits of Japanese art, both of which expose the sheer beauty of the country’s sophisticated craft and artistic traditions.

The Textile Museum’s “Woven Treasures of Japan’s Tawaraya Workshop” (Mar. 23 – Aug. 12) display the Japanese textile traditions of the Tawaraya, a still-operational silk workshop over 500 years old, that has woven fine silk garments for the Imperial Household for centuries. The National Gallery’s “Japanese Bird-and-Flower Paintings by It? Jakuch? (1716 – 1800),” on view only through the end of the month, exhibit Jakuch?’s thirty-scroll series of nature and wildlife, proving him to be an unprecedented innovator in style, technique and aesthetic. Both exhibits are a master class in composition, color and design, and both beg to be viewed live. In photographs they are impressive, but in person they are breathtaking.

(It must also be noted that the Sackler Gallery, on the National Mall, is hosting an overwhelming exhibit of printmaker Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), perhaps the most acclaimed artist in Japanese history, titled “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.” However, this exhibit demands coverage all its own, and thus is not included in this article.)

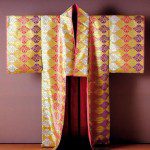

Based in Kyoto, Japan, the Tawaraya silk workshop is perhaps the oldest and most illustrious workshop in the country. While popular among the public for producing fabrics used in traditional theatrical costumes, Tawaraya is renowned for their production of yusoku orimono—garments of fine silks in patterns, weaves and color combinations traditionally reserved for the Japanese Imperial Household. On display in The Textile Museum, they read like an installation work, speaking of harmony, balance and serenity.

In a peculiar way, they are reminiscent of Sam Gilliam’s hanging fabric installation at The Phillips Collection, which closed almost a year ago. The Japanese fabrics of vibrant and subtle colors and ancient symbols, whose aesthetic is rooted in a centuries-old practice, become suddenly and hugely contemporary. This is a little ironic, as the man behind Tawaraya’s operations today, Hyoji Kitagawa, is the 18th-generation successor of this family-run workshop, who has painstakingly maintained silk weaving techniques passed down over a millennia, right down to dye recipes from the tenth century.

One remarkable aspect of these designs is the length that is taken in pursuit of subtlety and understatement. Where it is more familiar in the Western tradition for the elite to be wearing louder, flashier clothing, in Japanese aristocracy it would seem that bold symbols and wild colors are considered crass and unsophisticated. The Emperor’s yusoku orimono is composed of but pristine white and earthy brown ochre silks.

The patterns and symbols are similarly more nuanced. On the garments of a regular citizen, the symbol of a tortoise—which represents long life—would likely be a large, obvious and rather literal interpretation. On a yusoku orimono, the creature is represented by a pattern of hexagonal blocks, each one an individual shell, that stretch monochromatically across the silk. You will see cherry blossoms, cranes, pine trees, phoenix, bamboo and butterflies, each of which carry their own meaning and significance, but all of which are independently beautiful.

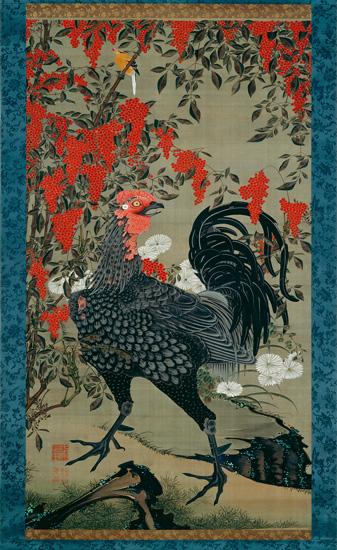

These symbols carry over to the National Gallery, where the 30 scrolls of 18th century Japanese painter Jakuch? might actually bowl you over. The expansive scrolls are intricate and effusive: a pair of chickens embroiled in a dynamic mating dance, feathers ruffled in exacting detail and eyes wild among a craggy hibiscus plant; an adumbrated landscape of seashells, crabs and starfish on the ocean’s floor; a wild goose in the reeds, hurtling toward a pond’s icy surface; a rooster amidst a plant of small, piercing red nandina berries. Yet within the paintings there is a fluidity of composition, a pristine sense of geometry and an unquantifiable harmony of color that link them to the same tradition as the Tawaraya silks.

Both offer an otherworldly glimpse of tradition, discipline and aesthetic near-perfection. The Japanese history is rich in artistic life, and Washington is lucky to have such resplendent exhibitions of their works to appreciate and compare.

For more information on “Woven Treasures of Japan’s Tawaraya Workshop,” on view through Aug. 12, visit www.TextileMuseum.org. For information on “Colorful Realm: Japanese Bird-and-Flower Paintings It? Jakuch?,” on view through April 29, visit www.nga.gov.

- Itō Jakuchū Nandina and Rooster, from Colorful Realm of Living Beings, set of 30 vertical hanging scrolls, c. 1757–1766 c. 1761-1765 ink and colors on silk 142.6 x 79.9 cm | Sannomaru Shōzōkan