The epoch of ukioy-e encapsulates the final phase of traditional Japanese history and a time of flourishing cultural arts from about 1600 through the 1860s. Due to the country’s policy of national seclusion (starting in the 1630s for fear of the impact of European colonial expansion on native culture), Japan was a world almost entirely unseen by foreign eyes until the late 19th century.

During this period of isolation, Japanese art acquired a singular character with few external influences. The style of ukiyo-e, which means “pictures of the floating world,” blended the realistic narratives of ancient picture scrolls with inspiration from the decorative arts and observation of nature. When these artistic traditions finally reached Europe and North America, their radical approaches to space, color and subject matter shook the Western tradition, revitalizing graphic design and penetrating the consciousness of painters from Monet to van Gogh.

Katsushika Hokusai (1760 – 1849), the ukiyo-e’s most prolific and renowned artist, produced an estimated 35,000 works during seven decades of ceaseless artistic creation. His images have matured into icons of world art, most famously his woodblock prints of Mount Fuji and its relationship with the surrounding villages and countryside. At the Sackler Gallery through June 17, “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” exhibits the full collection of Hokusai’s original prints, showcasing the intricate beauty, intimacy and grandiosity of these masterworks. They will leave you swooning and weak in the knees, enraptured by their ephemeral delicacy like a cherry blossom’s silky petals caught in spring’s first light.

Mount Fuji occupies a special place in Japanese culture. The ancient Japanese were sun worshipers and in the bustling city of Edo (modern Tokyo), this 12,000-foot volcano, resting like a lazy giant in the distant landscape, was the first piece of earth to catch light from the rising sun. A lifetime resident of Edo, Hokusai was intimately familiar with Mount Fuji’s snowcapped crest when he finally immortalized it in his print series at the age of seventy.

As a teenager, Hokusai apprenticed with a woodblock engraver, but quickly shifted his efforts to drawing and painting. Like most ukiyo-e artists, his career began as an illustrator for yellowbacks—cheap novelettes named for the color of their covers—before moving into illustrations for the major novelists of the day.

Hokusai’s work spanned the gamut of ukiyo-e subjects: album prints, genre scenes, historical events, landscape series, paintings on silk and privately commissioned prints for special occasions called surimono. Well regarded throughout Japan, his model books for amateur artists were very popular, as were his caricatures of occupations, customs and social behavior. From age twenty until the year of his death, Hokusai illustrated over 270 titles, including several books of his own art.

“But nothing I did before the age of seventy was worthy of attention,” said Hokusai, who envisioned his artistry maturing well past his centennial. Indeed, in the last two decades of his life Hokusai produced his finest work, unrivaled within the genre as the apex of the ukiyo-e tradition.

What Hokusai manages to capture in these prints precedes Impressionism in capturing the fleeting wonder of natural phenomena, realizing the texture and mood of atmosphere, seasonality, temperature and light. (It’s worth noting that Hokusai was actually rather familiar with European and Chinese art when he made these prints, as his country had by then opened international trade relations in some capacity, allowing glimpses of foreign artistic traditions.) In studying the mountain and its relationship to the surrounding world, Hokusai shows us the serenity and violence, the danger, mystery and allure of our natural world.

Perhaps another aspect of Hokusai’s genius was in bringing the tonal reservation and transient effusiveness of painting together with the bold, clean linear image-making and stark visual clarity of prints. The prints perfectly depict the external appearances of nature and symbolically interpret the vital energy forces found in the sea, wind and clouds.

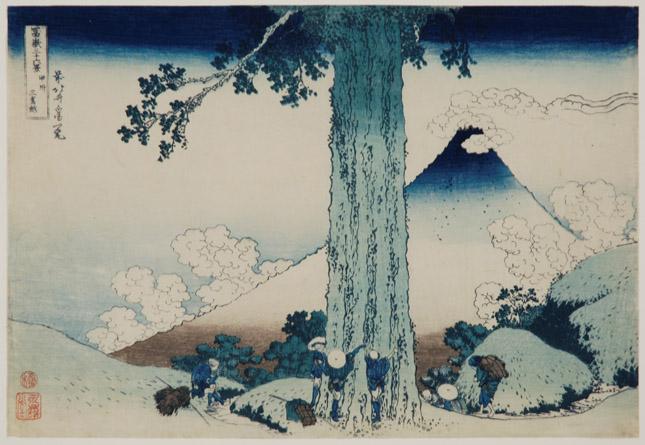

In “The Waterwheel at Onden” and “In the Mountains of Totomi Province,” the sinewy legs and worn bodies of the laborers give way to serene facial expressions, a common thread throughout the series, as if the physical burden of the land is but an inevitable accessory to the life it sustains. The agonizing labor plainly and literally depicted, inconceivable in the reality of its strenuousness, goes almost unnoticed in the works’ overwhelming peace and inner beauty.

This cosmic push-pull between man and the larger forces of nature is fully realized in the breathtaking “Kajikazawa in Kai Province,” where a fisherman stands dwarfed atop a craggy rock jutting out from a violent sea, his fishing lines taut against the ocean’s current and caught in a heavy fog from which Mount Fuji barely emerges in the background.

One of the show’s last prints, “Sunset on Ryogoku Bridge,” shows a pale grey sky, with the wine-hued boldness of an unseen sun saturating the Prussian blue waters and glowing green bridge. Mount Fuji hovers like a deep, luminescent shadow behind a cluster of dim houses. An old man stands in his boat, leaning on his oar and staring at the distant mountain, as if overwhelmed by the site. It is a beauty he cannot resist. It is also a feeling that viewers can associate with: a sense of floating in time, in a reality beyond what we see before us.

Above all, Hokusai’s prints are studies in reservation, balance and ritual, mirroring the sentiments of his culture in his ceaseless, patient pursuit of Mount Fuji. The confluence of life, labor and the natural world press on, immortal but impermanent, much like the woodblock engravings from which the prints were forged, worn down with each unforgettable printing until its sharp-edged clarity vanished into but a vague impression of its past self.

“Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” is on view at the Sackler Gallery through June 17. For more information visit Asia.SI.edu.