The Willard: Birthplace of ‘Battle Hymn’

By • June 18, 2013 0 2808

While historians generally believe the term “lobbyist” came from England circa 1800, it is part of our local lore that the term originated in the lobby of the Willard Hotel in downtown Washington. It seems that President U.S. Grant liked to slip away from the White House to enjoy a cigar and brandy at the nearby hotel. People in high places who wanted favors used to lie in wait for him, and hence the Washington version of the term “lobbyist.” Since the hotel’s 1986 period restoration, the lobby is so redolent of the 1860s, that one can easily imagine Grant stretched out in a velvet lounge chair behind one of the potted palms.

What you may not know is that another piece of 1860’s history was born at the Willard, before Grant was president and even before he assumed command of the Union Army. It had to do with the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, whose 150 year anniversary was celebrated this summer with speeches and re-enactments at the battleground park in Manassas, Va.

Early in the conflict, confident that they could defeat the South, the Union Army marched toward Richmond with the hope of bringing the war to a quick close. The North was so sure of itself that congressmen and dignitaries from Washington packed picnic lunches and rode their carriages behind the army so they could watch their soldiers win the day. Instead, the northerners met with fierce resistance from the strong southern army they encountered in Manassas. This was the battle where Confederate General Thomas Jonathan Jackson earned the nickname “Stonewall” for not giving up his position, and where the first civilian casualty of the war occurred, when the 85-year-old woman who owned the house on Henry Hill was killed in the cannon crossfire. The battle lasted five hours with many casualties on both sides, and ended with the Union army turning back and fleeing toward Washington. The civilians quickly turned their carriages around to head back east, got mixed in with the retreating soldiers, and created a massive traffic jam with panicked soldiers and civilians running in all directions.

As a result of this battle, morale in the Union Army was at low ebb, and the generals had a hard time recruiting soldiers. A New England abolitionist named Julia Ward Howe was afraid that the North might lose and slavery would not be defeated. So, she came to Washington to see if she could help. While Howe was in town staying at the Willard Hotel, she heard soldiers singing “John Brown’s Body” outside her open window. She liked the melody but thought it was a shame there weren’t better words to go with the song. When she awoke up in the middle of the night, she was suddenly wide awake and began writing verses to the melody, which she later sold to The Atlantic Monthly magazine for $5.

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” became one of our most beloved patriotic songs, and on the front of the Willard Hotel, a plaque commemorates Julia Ward Howe for writing the verses that led Union troops into battle through the next four terrible years, until they were, as the song promised, victorious.

Here is one more story about the Willard: as we celebrate the new memorial to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., it’s interesting to know that he stayed at the Willard in 1963, almost 100 years after Howe’s visit, in the days before he gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. When you think of him sitting in his room going over the words of his history-changing speech, you have to believe that inspiration must live in those walls.

Donna Evers, devers@eversco.com, is the owner and broker of Evers & Co. Real Estate, the largest woman owned and run real estate company in the Washington Metro area; the proprietor of Twin Oaks Tavern Winery in Bluemont, Virginia; and a devoted fan of Washington history.

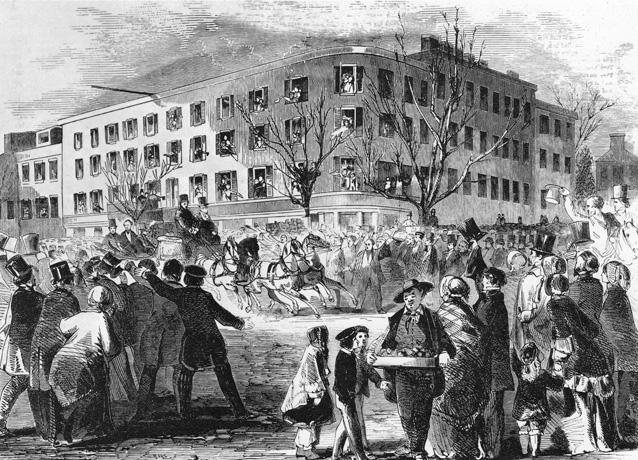

- The Willard as it was.