BELLOWS AND MIRÓ: Painting the Cultural Fabric

By • August 15, 2013 0 1330

Within the stone walls of the National Gallery of Art, the calm, quiet rooms are always cool and astonishingly breezy. Perhaps this is in order to preserve many of the collection’s centuries-old masterpieces, but to all who enter it is simply a fine refresher. It probably won’t surprise you to learn that, for this writer, there is no better way to escape the oppressive summer heat than to dip into one of the exhibits and look around.

This summer, however, a different kind of heat is emanating from inside the gallery walls. It is almost imperceptible, but if you look closely you can see it, like gas rippling up from the stovetop. It is a political and social heat that radiates from the canvases and wraps itself around you. It is coming from the works of George Bellows and Joan Miró, both the subjects of major exhibitions at the National Gallery.

At first glance there are not many similarities between the two artists, in their style or their history. Miró (1893 – 1983) was born in Barcelona, Spain. He was a member of the European avant-garde, an artist-activist who shot into prominence on the coattails of cubism and surrealism. Fusing the artistic innovations of his day with the heritage from his native region of Catalonia, Miró forged a voice and vision in his paintings that would influence future generations of artists worldwide. The current exhibition at the National Gallery, “Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape” (through August 12), showcases the artist’s political engagement and his battle for a collective Catalan identity throughout the militaristic and social tumult of the 20th century.

Bellows (1882 – 1925), on the other hand, was an American realist painter born and raised in Columbus, Ohio, a gifted draftsman and athlete who almost took the route of professional baseball player before moving to New York City to study painting. An original member of the Ashcan School, Bellows is largely remembered for his portraits of contemporary American society, urban subject matter and the working class—and, memorably, the seedy underbelly of early New York City boxing culture. The National Gallery is exhibiting a retrospective of Bellows’ work through Oct. 8.

Aesthetically, there could not be a more dissimilar pair of artists than George Bellows and Joan Miró. One offers a gritty, unflinching portrait of American realism, the other an effusive and ever-evolving synthesis of the folkloric, the abstract, the subconscious and the colorfully raw. But there is a bridge between these two monumental and otherwise incongruous exhibits that brings the artists to common ground. Both expose men of dire social conscience, whose painting careers and cultural sentiments wove together to create bodies of works that transcended a singular time or place and carry on their lasting legacies.

In the first room of the Miró exhibit, you are met with intricate canvases of farms and gardens, corroded stucco houses cankered with vines and ivy, detailed to the point of compulsion—every seed, blade of grass and cracked windowpane is meticulously, if simply, rendered. The paintings are enchanted with that sense of something greater, as if we are just getting a surface glimpse of a rich and endless landscape. This plays out most pointedly in “The Farm,” which, according to the artist, “was a resume of my entire life in the country.”

This early painting, completed in 1922, roots Miró firmly in an ideology that would thread itself through his oeuvre. The scrutiny over familiar landscapes is the first sign of his engagement with political identity: the cultural specificity, locality and autonomy with which he renders the land of his ancestors is a cry for Catalan culture.

“Miró was reaching back to Catalan Romanesque art as a way to resurrect his ancestry,” says Harry Cooper, curator of modern art at the National Gallery. The narrative forms of Miró’s earlier work point toward these characteristic church murals, while the shapes, structures and colors combine influence from cubism, fauvism and the breathtaking architectural work of fellow Catalan, Antoni Gaudí.

Around this time, the Spanish government outlawed the Catalan flag and language, and a series of events unfolded that would lead to the Spanish Civil War. The political turmoil outraged Miró and as his feelings grew deeper, his paintings became increasingly disturbing and violent.

Cooper notes how just a year after “The Farm,” Miró’s painting, “The Hunter” took these sociopolitical allusions to a far more scathing level. “It was painted only a year or so later, but the difference in style and voice is pretty astonishing. The Catalan flag and the French flag hang side by side, and the Spanish flag hangs alone on the other side of the canvas. You can see that things got political pretty immediately with Miró,” Cooper says.

Perhaps what is more astonishing is that Miró executed these ideas in an entirely distinctive, individual language all his own (a pursuit also likely inspired by Gaudí).

“I understand the artist to be someone who, amidst the silence of others, uses his voice to say something,” Miró once wrote, “and who has the obligation that this thing not be useless but something that offers a service to man.”

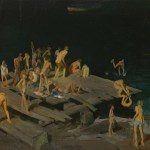

Just ten years before and across the Atlantic, Bellows had spoken up loudly against New York City’s social and economic class structures. His paintings of tenement children, construction workers and the cheap leisure escapes of the working class are treated with a painterly regard previously reserved for only the Dionysian pursuits of the most affluent. Imagine seeing Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” but swap out the airy middle-class Frenchmen with puffy-faced, malnourished orphans and haggard bricklayers. The titles alone are enough to give an idea: “Paddy Flannigan,” “Frankie the Organ Boy” and “River Rats.”

Imbuing New York City’s immigrants, laborers and impoverished families with the rites of the societal elite suggests how Bellows perceived these communities as the brick-and-mortar foundation of his country. Throughout his career Bellows painted men and women in almost every walk of life, yet these paintings remain his most powerful and haunting.

Through the somber shadows surrounding these men’s works, an undeniable joy nonetheless permeates. You can see it in Bellows’s rhythmic, effusive brushwork, songlike in their fluency and syncopation. It is visible in Miró’s sun-kissed color palette and his wholly liberated, original forms, like new life taking shape before our eyes. There is love amidst the rage, serenity is found in the chaos, beauty and bile are all interwoven, just as they are throughout every town and country in the history of mankind.

George Bellows and Joan Miró shared this understanding, this gift for portraying true life. Go see it play out before they’re gone.

For more information, visit www.nga.gov. ?

- Forty-two Kids, 1907; oil on canvas overall: 106.7 x 152.4 cm (42 x 60 in.) Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, Museum Purchase, William A. Clark Fund | George Bellows