Andrew Wyeth at the National Gallery: ‘Looking Out, Looking In’

By • May 22, 2014 0 3076

The thought of a mid-to-late 20th-century artist painting washed out landscapes of rural America and being hailed as a cultural icon and national treasure is almost unimaginable. In the most aggressively transformative century in recorded history, the geography of art alone shifted so drastically and disparately that it is virtually impossible to sum up its evolution. Compared with Cubism, performance art, film and digital media, a pastoral scene of meadow grass and an old barn does not seem like much at all.

Yet Andrew Wyeth, a rural painter of American regionalist life and landscapes from Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, managed to capture the imagination of this full-throttle era, and his work continues to challenge and inspire new generations to this day.

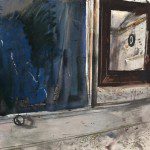

At the National Gallery of Art through Nov. 30, “Andrew Wyeth: Looking Out, Looking In,” is a new exhibit centered around the recent acquisition of one of the artist’s seminal paintings, “Wind from the Sea” (1947). This is the first fully realized exploration of Wyeth’s frequent use of windows as subjects in his work, showcasing some 60 watercolors, drawings and tempera paintings. It reveals how the artist returned to windows repeatedly, probing the formal and conceptual richness of this most common subject in his and all our lives.

The works in this exhibit are haunted by ghostly shadows and memories that lie just beyond the picture plane. Wyeth devoted himself to visual art when he was still a child, trained by his father, the renowned but troubled illustrator N.C. Wyeth, whose paintings for such literary classics as ‘Treasure Island’ remain among the most acclaimed illustrations of all time. From his father, Wyeth inherited a love of nature and poetry, particularly an affinity for Robert Frost, but it seems like he absorbed a great deal of subtle, narrative illusory qualities as well. However, unburdened by the shackles of commercial illustration, Wyeth was able to realize a far greater level of dissonance and durability than his father’s work could ever achieve.

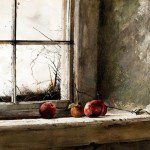

Windows allow for reflection, as seen in the watercolor “Rod and Reel” (1975), where a darkly reflective window set into a whitewashed wall slowly reveals tiers of subtly fragmented landscapes from the adjacent farmland through the glass. Onlookers are suddenly brought into an unexpectedly dimensional world on the surface of the paper.

The idea of reflections is fitting, as this collective work becomes a journey into the artist’s mind – which in Wyeth’s case dwarfs almost any effort by Surrealism to explore the depths of the unconscious. Wyeth lived most of his life in his Brandywine Valley hometown and at his summer home in Cushing, Maine, where the familiarity with his environment grew so intimate that he was able to truly divest himself of self-awareness and external forces of judgment. He spent so much time painting these scenes that they became a part of him, and so the work is at once an exact portrait of the artist’s mind as well as the reality of the subject. And Wyeth’s painterly expression of this duality gets contentedly lost within its own schism.

The paintings have a temporal haze to them, as if they could just vanish at any moment; the atmosphere he manages to produce is a depiction of something that can really be seen only in a state of unfocused rumination. (This idea might be an indication as to why Wyeth always insisted he was an “abstract” painter.)

There are occasional moments in his works where things just vanish, as in his tempera painting “Seed Corn” (1948). A high window looks out onto a sprawling gray landscape, with strung-up corn on either side drying out for the next season’s seeds. Peculiarly, the center rail of the window just disappears halfway out, fading into the muddy gray sky. At first it seems like a shallow surrealist gesture, but really it is much purer than that. It’s as if Wyeth had lost sight of the fact that the rest of the window even existed, as his eyes and brush strayed out toward the rolling hills beyond. And the strange thing is it looks perfectly natural.

Some of Wyeth’s appeal is absolutely his technical facility with his medium. His work offers such spoils of formal virtuosity, floating between hyperrealism and textured painterly richness, that scholars and museum-goers alike should swoon with awe.

From a historical perspective, there is also a great deal to play with. In many of these paintings, it is difficult to ignore the undertones of Wyeth’s contemporary influence, from the geometric purity of Piet Mondrian or Franz Kline, to the softer geometric haze of Hans Hofmann or Mark Rothko, and even the textural harmony and distributed brushwork of Mark Tobey’s all-over early abstract style of painting.

From the early regional side of things, there are parallels between Wyeth’s work and the atmospheric landscapes of forgotten early American painters like Dwight Tryon, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, John Henry Twachtman and Albert Pinkham Ryder. Of course, a great deal is further owed to his predecessors Thomas Eakins and James McNeill Whistler as well, but quite frankly this game could go on forever.

One mark of a great artist is surely their ability to influence an audience to think and consider their surroundings. In the case of Wyeth, his subject is perhaps thought and environment itself. It is the moment when we look out a window into the gray sky, catching a glimpse of mortality as we ponder our myriad little human dilemmas, mired by history and personal experience but singularly products of our own creation, moving unavoidably into the future.

*“Andrew Wyeth: Looking Out, Looking In” is on view at the National Gallery of Art through Nov. 30. For more information, visit [www.nga.gov](http://www.nga.gov).*

- Rod and Reel, 1975 | Andrew Wyeth