‘Conversations’ at the Museum of African Art

By • April 23, 2015 0 1028

As titles go, “Conversations” is a perfect distillation of the sprawling body of work now on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art. To celebrate its unique history, the museum has mounted “Conversations: African and African American Artworks in Dialogue” as part of its 50th anniversary.

The exhibition, on view through Jan. 24, 2016, brings together pieces from the museum’s collection with others from the landmark African American art collection of Camille and Bill Cosby.

And, yes, it is that Bill Cosby. It would be foolish to ignore the inevitable wave of vitriol that his name now conjures, and which will very likely haunt him for the remainder of his life. However, it is just as irrelevant and naïve to condemn a successful and moving museum exhibition in order to admonish a television celebrity who owns some of the artwork on loan. So, as regrettable as it is to begin this way, let us clear the air in order to move on.

First, it takes a very long time to mount a museum exhibition. By the time the allegations against Cosby were brought forth last year, this show was, for all purposes, mounted, funded and finished.

Second, we must make a distinction between art and current affairs, which includes forgoing who the owner of a painting is at a given point in time. As an enormously unfair (but bluntly effective) example, the Vermeer painting, “The Astronomer,” today under the stewardship of the Louvre, was for a time among the prized possessions of Adolf Hitler. Do we censure the museum? Destroy the painting? Of course not.

The point is that, by and large, art has the capacity to move through time, outliving the fickle temporality of social and political tangles. We can stand before an Aegean fresco from the 15th century B.C. and subject it to the same terms as Jeff Koons’s flowery “Puppy” sculpture in Bilbao. Art is relative, and that is a piece of its great and lasting beauty.

So let’s talk about this exhibition, which is exceptional. “Conversations” offers virtually endless connections and perspectives into the ways that artists have explored complex ideas about the social, political and aesthetic roles of art in African and African American contexts and identities.

To this end, nearly every work in the exhibition is shown alongside a related counter-work, offering a clear and real juxtaposition of similar or divergent ideas. “Benin Head,” a painting by American artist David Driskell (b. 1931), hangs beside a commemorative Nigerian portrait-carving from the 18th century made in the court style of the Kingdom of Benin. Here, the contours and planes of the carved head illuminate the clear influence upon Driskell of the African work of that period.

A nearly identical – if less direct – line can be traced in the thematic section titled The Human Presence between male and female figures carved in wood by a mid-20th-century Senufo artist from Côte d’Ivoire and a marble sculpture by African American artist Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012), “The Family,” depicting a man and a woman raveled in an embrace. Works like these are marked by their aesthetic relationships: bound by style, subject and a conscious effort by contemporary artists to unite with the heritage of their forebears.

But there are less direct conversations within the exhibition as well, in many cases presenting fascinating challenges to oversimplified presumptions. Take, for instance, an untitled pastel drawing by Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), the prodigal New York graffiti artist. This is a quintessential Basquiat drawing, a gritty, visceral scribble. Its broken, aggressive lines and dented circles seem to come together through some act of cyclonic magnetism, forming a proto-grunge voodoo doll of a human figure on the mutilated surface of the paper.

Beside this drawing is a neat colonial portrait of a white American woman and her daughter in white lace. The biracial artist, Joshua Johnson (1763-1824), a portraitist of prominent Marylanders, is often viewed as the first person of color to make a living as a painter in the United States.

The exhibition is too smart and too thoughtful for this pairing to be coincidental. Both Basquiat and Johnson were near-isolated minorities who single-handedly cracked the code of the white-controlled mainstream art culture, shifting the vantage point in both periods.

Masterworks abound in the exhibition, from “Nexus” by Martin Puryear (b. 1941), a beautifully crafted, evocatively minimal ring-shaped sculpture made from bent saplings of laminated wood, to “The Thankful Poor” by Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), a delicately hazy, brilliantly atmospheric oil painting of a black boy and his grandfather praying at the breakfast table.

There is also a myriad of unclaimed gems that skate the border of art and historic treasure, such as an Orthodox-style Ethiopian icon – sharply juxtaposed beside Tanner’s painting – and a collection of musical sculptures and carved drums from Ghana and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The latter forms the centerpiece of the unmissable “music” gallery.

This facilitation of contextual connections is something too often lacking (or otherwise poorly executed) in a museum experience. The National Museum of African Art has mounted a terrific exhibition, which fills the deep and seemingly unresolvable gaps between the devastating estrangement of African and African American heritage.

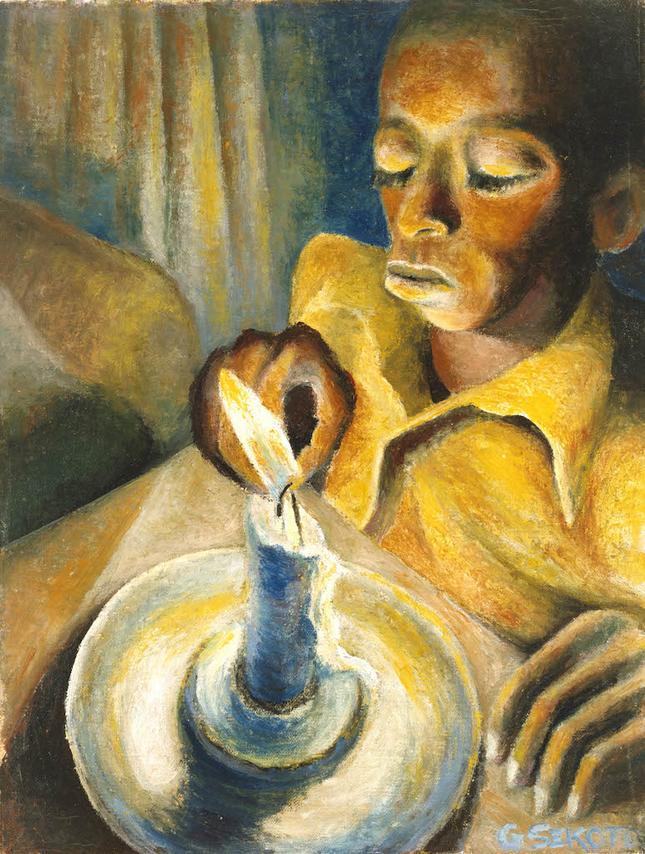

- Gerard Sekoto, “Boy and the Candle,” 1943. National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution. | Jordan Wright