By • October 26, 2016 0 789

In a world where conflict among tribes, nations, regions, religions are the norm, it’s a blessing to live in Washington, where we have a wealth of think tanks, policy centers, lecture series and museums (for free, usually) to help us sort things out and make our way through the countless cultures on the planet.

Notably, we have the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer and Sackler Galleries, which together “comprise the nation’s museum of Asian art.” This description doesn’t tell you much, either about the breadth or the depth of the collections, or, perhaps more important, about their impact.

The sheer volume is impressive: more than 40,000 objects dating from Neolithic times to our own, from China, Japan, Korea, South and Southeast and Central Asia and the Near East. The collections contain worlds within worlds. While people are almost predisposed to think about other peoples in terms of clichés — cultural, social, religious, political — what the galleries have consistently allowed us to see are the artistic achievements of peoples with whom we interact in places that today are roiling with conflict and competing interests.

The 93-year-old Freer Gallery of Art — famously also home to James McNeill Whistler’s Peacock Room — is currently undergoing extensive renovations; it is expected to reopen Oct. 7, 2017. When the linked Arthur M. Sackler Gallery opened in 1987, it not only supplemented the Freer’s permanent holdings but enabled the conjoined buildings to host special exhibitions.

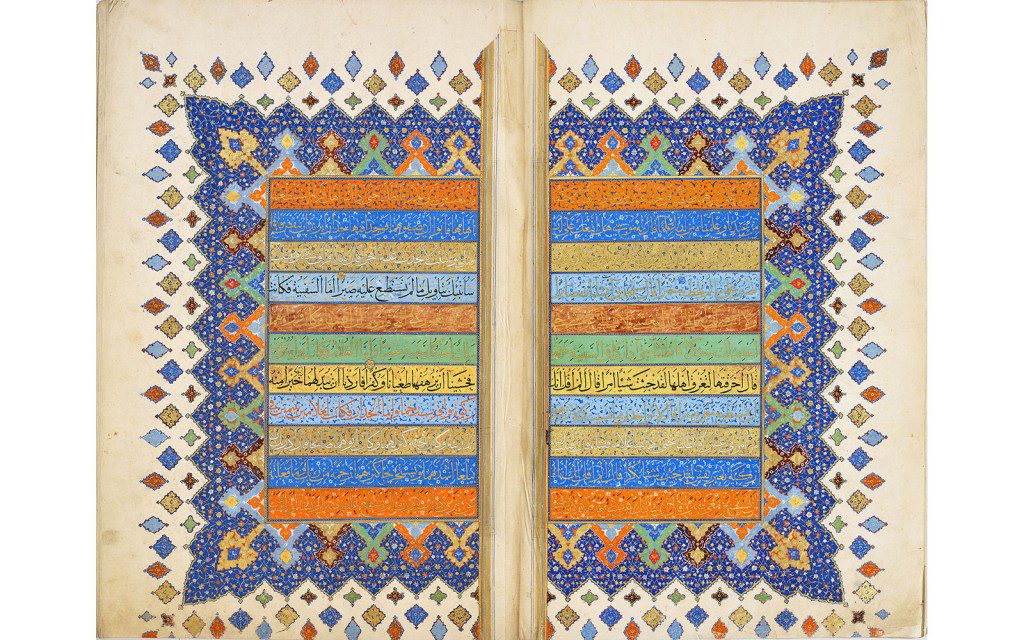

A current and major example is “The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts,” which is hailed as “the first major exhibition of Islam’s holy text in the United States.” The exhibition — which officially opened Oct. 22 and will continue through Feb. 20 — features more than 68 of the most important Qur’an manuscripts from the Arab world, Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan. The lender, the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, occupies the former palace of Suleiman the Magnificent’s second grand vizier in Istanbul.

Looking at these manuscripts, replete with lavish illumination and delicate, intricate calligraphy, we seem to be gazing at time itself. They span roughly a thousand years in history, beginning in eighth-century Damascus in Syria and continuing through and after the 16th- and 17th-century height of the far-reaching Ottoman Empire.

The names found in the origins and journeys of the various manuscripts strike a chord straight out of the daily headlines from the Middle East, the stories of refugees and strife that have become a part of our daily diet of news. Those reports, however, fail to communicate the complex symbolism and beauty, the essence of Islam contained in these extraordinary Qur’anic manuscripts.

Islam began as an orally received religion. But the Qur’an — popularly known in the West as the Koran — transformed the word of God, as received by the Prophet Muhammad through the Archangel Gabriel in the year 610, from oral transmission to written. For centuries after, the sacred text was reproduced and illuminated by supremely accomplished artists throughout the Islamic world.

In addition to being the religion’s physical manifestations, the manuscripts, often made for rulers and other members of the Islamic elite, were works of art in and of themselves, creations of great beauty. Their history is a window into the history of Islam and of the countries and empires where it flourished.

According to Massumeh Farhad, chief curator and curator of Islamic art: “This exhibition offers a unique opportunity to see Qur’ans of different origins, formats and styles and begin to appreciate the power and beauty of calligraphy as well as intricacy of the illuminated decoration.” Julian Raby, the Dame Jillian Sackler Director of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the Freer Gallery of Art, pointed out that many of the works had never before left Turkey. “Some were unknown even to scholars,” said Raby, himself an expert in Islamic art.

“The Art of the Qur’an” is part of a series of exhibitions at the Sackler under the umbrella of “Arts of the Islamic World,” also including “Turquoise Mountain: Artists Transforming Afghanistan” (through Jan. 29) and “Sky Blue: Color in Ceramics of the Islamic World” (through July 16).