“Stuart Davis: In Full Swing” at the National Gallery

By • January 11, 2017 0 1485

I was 17 when I first saw Willem de Kooning’s black-and-white paintings from the late 1940s. These were the years just before his legacy was cemented in history, before there was much money in American art, when he struggled to pay his rent and drank coffee because alcohol was too expensive.

He used enamel, cheap commercial-grade house paint, which only underscores the austere, workmanlike urgency radiating from the canvases. It looked to me as if he couldn’t get the paintings out fast enough, each one an encrypted message scribbled desperately in a fever dream.

With a brusque, tactile magnetism and a bounty of historical lore in tow, these paintings catapulted a tamely frustrated teenage art student toward an inescapable and insufferably masculine fixation with midcentury American art: Pollock, Rothko, Marca-Relli, Tworkov, Kline. I would not know for years how typical my story was.

Perhaps because of the awestruck skew of my lenses, I long believed that the artistic energy of this period was born in something of a vacuum. It was my feeling that the frenetic visual lexicon of the ’40s and ’50s, which compounded the rhythmic bebop of postwar American aesthetics with European modernism into a pure visual abstraction, was something forged from the raw by a handful of exceptional artists when history presented an opportunity.

Obviously I knew this was not true, that art is in essence built from shared history, but for many years I never came across any work that I felt entirely invalidated my opinion. Then I saw the work of Stuart Davis.

At the National Gallery through March 5, “Stuart Davis: In Full Swing” moves through five decades of the painter’s groundbreaking career, from his early post-Ashcan days amid the influence of Cubism through his steady construction of a geometric visual language that brilliantly heralds many essential principles of postwar American art, from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art.

Born in Philadelphia to artists and raised in East Orange, New Jersey, Davis devoted himself to painting early, dropping out of high school to study in Manhattan with Robert Henri, the legendary teacher who urged his students — among them, George Bellows, Rockwell Kent and Edward Hopper — to sketch daily life, ignore convention and find their own voices.

Another early and lasting influence was the poetry of Walt Whitman, “our one big artist.” In his journal, Davis once wrote that he hoped to capture “the thing Whitman felt — America.”

It should probably be said here, before my praise gets too far out of hand, that Davis in many respects was working in step with the shifting American scene. He certainly didn’t invent all these things on his own. Among other artists, I could write similarly of early American modernists like Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove or even Arshile Gorky, the proverbial godfather of Abstract Expressionism.

But the reason Davis stands out has to do with the way he captured the specific energy of postwar America, particularly the buzzing beauty of New York City. There is a roiling enthusiasm about his work that defies its cold geometric frameworks. The way shapes and colors move through each other with increasing fluidity over his career, always isolated and interweaving like a tapestry or cut paper — he seems to have not mixed colors on his canvas since the early 1920s — elicits the skittishly syncopated harmonies of jazz. (On Davis’s connection to jazz, see Philip Kennicott’s coverage of this exhibition for the Washington Post.)

At the same time, his compulsive reworking of compositions and repeating of motifs over decades was both investigatory and savagely self-critical. While obviously influenced by jazz, the process also reinforced a poetry of urban environments that almost no other artist has captured so well (Léger comes to mind).

Taken together — a rare opportunity afforded by this exhibition — Davis’s body of work exudes the miraculous immediacy and vitality of a hungry city, both in its soaring, dimensional physicality and the bustling, entangled staccato of its human activity.

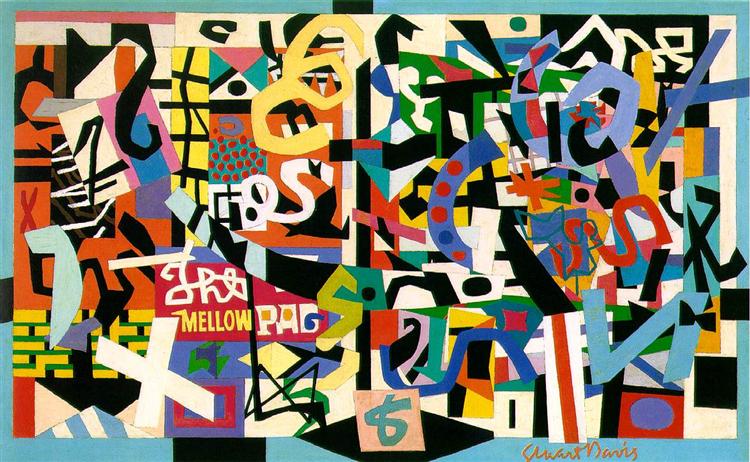

If there were only one great painting in this exhibition, it would be “The Mellow Pad,” a fulmination of Davis’s free-form deconstruction of color, architecture, urban environment, text, shape and line.

Made over six years as he struggled with personal hardship, between 1945 and 1951, it is remarkable to note that it was painted at the same time as de Kooning’s 1948 masterpiece “Asheville,” which took de Kooning a similarly extended spell to complete (an entire summer, but it is the only painting he worked on). The two paintings share an energy and a compositional trajectory; it is impossible to see them and not to beg a connection.

I’m not saying Davis directly inspired de Kooning or otherwise. I suppose I’m just admitting — and maybe just to myself — that de Kooning didn’t just make it up on his own. Because Davis had been living in that pad for quite some time already.

Davis is truly one of the deans of American painting, aware of all movements yet beholden to none. Embracing high and “low” culture, abstraction and realism, image and text, his vision was remarkable for its breadth and inventiveness. Don’t miss this show.