Toulouse-Lautrec at the Phillips Collection

By • February 8, 2017 0 1553

Of all the Post-Impressionists in 19th-century France, perhaps no artist has maintained such a lasting cultural influence as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Admittedly, there is an audacity to that claim. This was the very time and place of Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cezanne. The statement is also reductive and a little sensational, which is not the way art deserves to be understood. And while the popular history of art is in some manner the result of good marketing, artistic influence is fairly unquantifiable.

However, beyond the comparatively esoteric evolution of painterly perception, subject matter, color theory and spatial deconstruction by which we typically gauge art-historical development, Toulouse-Lautrec pioneered something altogether new and fundamentally radical in Western art. At the onset of new innovations in printmaking, he stepped in to define a new form of art, plastering the streets of Paris with large-scale lithograph posters and laying the foundation for graphic design and illustration in the 20th century.

This was art for the masses, designed to be reproducible and with specific economic intention: to attract customers. It is the art that dominates the world, seen daily by almost all people. And Toulouse-Lautrec’s influence is still deeply felt, plainly visible in everything from movie posters to vector images in logos and print advertisements to the silhouetted figures dancing wildly in iPhone commercials.

The Phillips Collection, an esteemed institution, would never release a statement as foolish and unverifiable as my opening line, but their new exhibition, “Toulouse-Lautrec Illustrates the Belle Époque,” on view through April 30, makes a strong case as to why I might be right.

This is an extraordinary collection of the artist’s iconic and rare printed works from nearly the entire period of his lithographic career (1891-9), many of them shown for the first time in the United States. It is a journey into printmaking, as well as into the smoky cafés, cabarets and dance halls of turn-of-the-century Paris.

Toulouse-Lautrec was the son of a wealthy noble family from Albi, in southern France. His parents were first cousins and he suffered from congenital health conditions throughout his life. After he fractured both his femurs in early adolescence and neither healed properly, he grew to be an extremely short man with an adult-sized torso, retaining his child-sized legs. Barred from the boisterous physicality and adventure of youth, he took to art.

After training with academic painters in Paris, he set up a studio in bohemian Montmartre. Perhaps due to his peculiar and unthreatening stature, he became greatly adored by the dancers, prostitutes and proprietors of the nightclubs he frequented: the Chat Noir, the Mirliton, the Moulin Rouge. His behind-the-scenes impressions of these local amusements fashioned a portrait of modern life.

His arrival in Paris also coincided with the revival of and innovations in the technology of color lithography, as well as a relaxation in municipal regulations as to what could be put on walls for advertising. The sheer scale of the posters around the city transformed Paris into an open-air exhibition, while limited-edition lithographs and print albums designed for the home catered to collectors. Toulouse-Lautrec’s embrace of printmaking and experiments with the medium — which, unlike most artists of the time, he respected on the same level as painting and drawing — revolutionized the field.

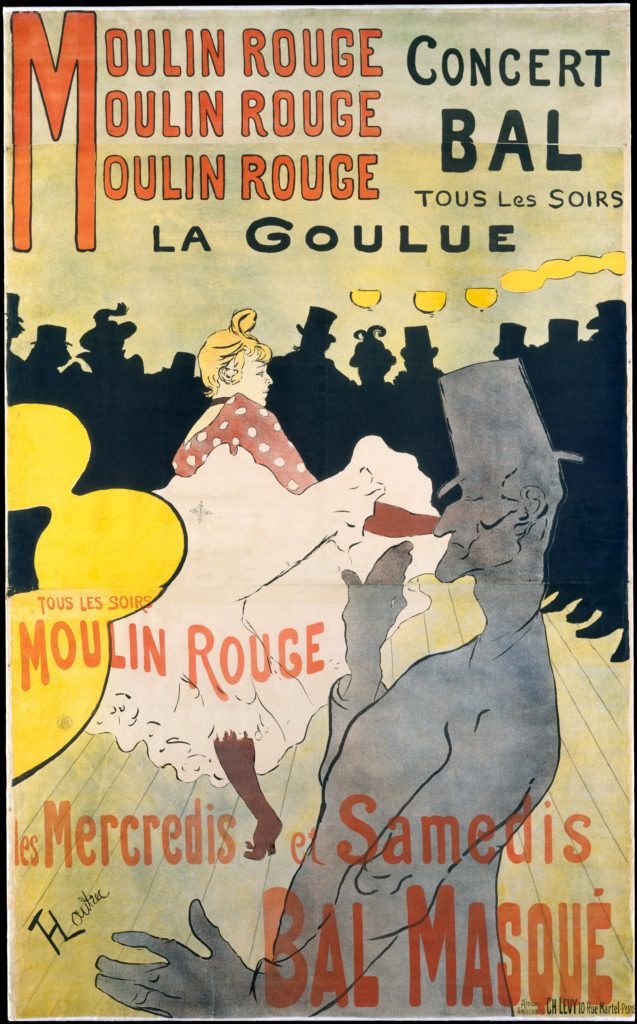

It is remarkable that his most famous print, “Moulin Rouge, La Goulue” of 1891, was his first. Upon entering the exhibition, this poster greets you with remarkable energy. Printed on three sheets at a massive scale, the design uses cropped forms and silhouettes to create a visual language unique to posters at the time (which, of course, we all now take for granted).

Toulouse-Lautrec encapsulated the important features of his subjects, distilling them to their most basic and significant elements, paving the way for modern illustration and editorial cartoons. His posters are provocative invitations, enticing viewers with a convivial spirit to make them want to enter the drunken, gas-lit dreamscapes of the clubs.

As an original champion of the poster as a way to get art to the masses, it is in a way natural that his model would become so widely influential, though like his contemporaries he took a great deal of his inspiration from the Japanese ukiyo-e prints beginning to reach Europe.

The exhibition also highlights the artist’s exacting, virtuosic workmanship. It is a rare treat to see proofs and test prints of many of his iconic posters, which illuminate this master of mood and environment’s process in creating what seem like effortless and perfectly balanced designs.

After all is said and done, I can tell you now that I am terribly biased and probably unfit to write an equitable review of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work. I have his signature tattooed on my right leg. Then again, maybe this is just further proof of his lasting and permanent influence.