June Schwarcz at the Renwick

By • April 5, 2017 0 675

Generally speaking, the “how” of art is not something that particularly interests me. A great deal of expository efforts go into exhibition descriptions of contemporary and craft artists, in which museums and galleries expound upon material techniques and working methods.

There are good and bad reasons for this. All fine art is to some degree a craft, and for modern audiences the discussion of art’s physicality can be far more relatable and engaging than the flowery, bombastic prose of art-industry critical analysis.

Yet the manner of an artist’s technique is only incidental to how successfully his or her work functions as art — how well it captures the attention and interest of its viewers.

There are probably thousands of living technical experts in oil paint with profound working knowledge of pigments, glazing techniques, tools, color theory and art history (I have met a few of them). They mostly paint landscapes. And that knowledge rarely translates into a body of work that is popular, provocative, influential or even necessarily good.

This is oddly analogous to blockbuster action movies: no one actually cares about how the visual effects were achieved. They are supposed to look great. If the film is good, the effects become a key component to its success. But if the movie is a dud, no amount of digital enhancement will save it; the effort that went into them is inconsequential.

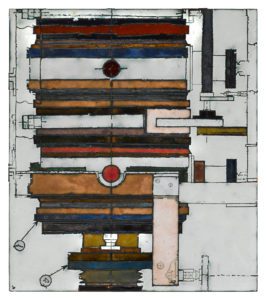

“SLAC Drawing III (#646),” 1974. Photo by Cate Hurst. Collection of Carl Schwarcz and Molly Clark. © The June Schwarcz Estate.

Good artists of any medium figure out what they need to. Degrees of technical proficiency vary, but rarely anymore is that the key to an artist’s success. The toil of studio practice can yield surprising and unexpected results that take work in new directions, but it takes a rare artist with particular vision to be receptive to those moments and build out of them a significant body of work.

All this is to say that I was incredibly taken with both the technicality and aesthetic pleasures of enamel artist June Schwarcz.

Born in 1918, Schwarcz was a pioneering artist, one of the most innovative enamelists of the 20th century. Her technical innovations combined with her inventive and unorthodox designs set new standards for enamel vessels and wall hangings, establishing her as a leading voice in American art.

At the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum through Aug. 27, “June Schwarcz: Invention and Variation” is a retrospective exhibition that includes nearly 60 of her forms, from vases, bowls and three-dimensional objects to wall-mounted plaques and panels.

There is a stunning variety of objects on display, each containing worlds within worlds of luminous, tactile intrigue and colors ranging from rich neon to the softest earth tones.

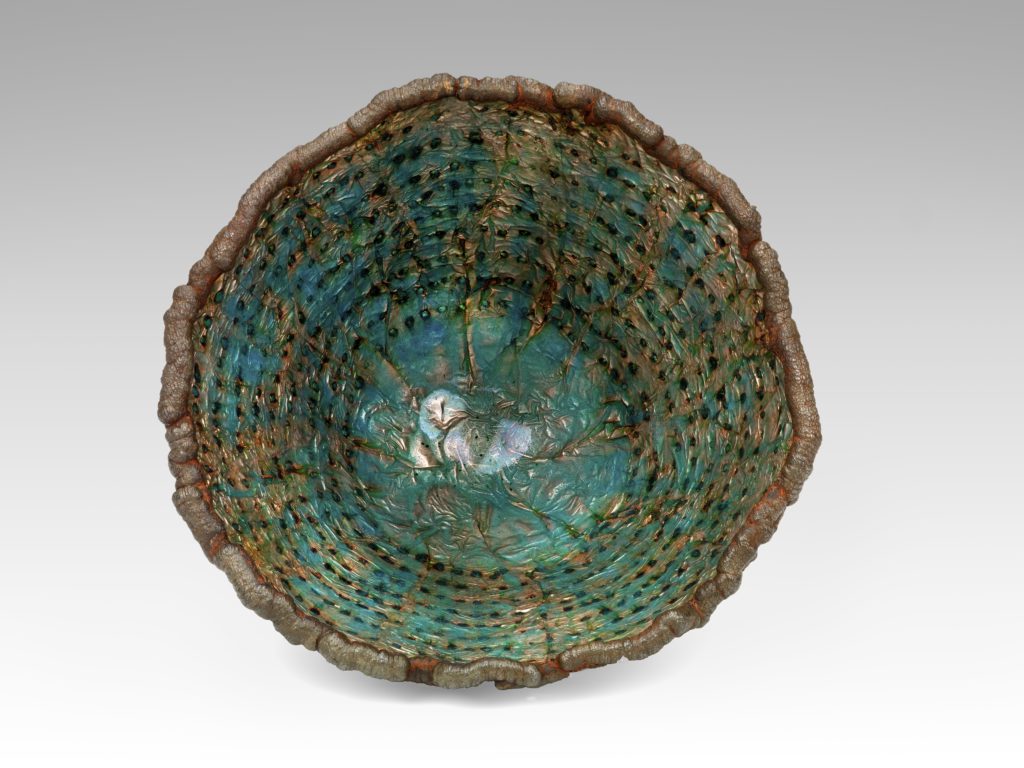

Schwarcz, who died in 2015, achieved her effects with confounding techniques, yet she was able to give in to the mystery of their beauty. For instance, fascinated by the random ways that accretions built up in the plating tank, she painstakingly stitched together a series of bowls to which she then abandoned control.

“It’s like gambling,” she said. “I go through so many processes, and I don’t know how something is going to come out. Sometimes something just works, sometimes it doesn’t…. That makes the process continually exciting.”

The bowls are exquisite. Folded, pinched, Swiss-cheesed and spun, each vessel carries a weight of history and beauty, riches and ruin, reminiscent of the finest ceramic artifacts of Greek and Middle Eastern origins. One bowl in particular, with a cankered, rust-colored exterior and a jagged lip, encircled with small holes, opens like a flower into a glowering coal-red cradle.

Using sandblasting, Schwarcz manipulated the surface of other vessels to create rich textural variety, mitigating the gloss of the enamel and creating varied finishes. Like dented oil canisters in an abandoned garage, a few busted-looking small canisters oscillate between a coppery corrosion and an iridescent blue-green. One would almost think it was the play of light against chemically tainted metal, but it is Schwarcz’s masterful sense for color and spatial effects.

In the late 1960s, Schwarcz began to produce plique-á-jour, transparent enamels suspended within an open, unbacked metal framework and then fired. The result looks like small stained glass windows, allowing light to shine through. She wanted the glazed openings in her vessels to be subtle, so she created heavily encrusted surfaces in the plating tank, often patinating them with chemical solutions. Craggy and raw, they contrast with the glazed areas of the vessels and their glossy interiors.

This is not even a quarter of the different techniques and approaches on display that Schwarcz employed during a career of more than 60 years. Nor does it begin to touch on her myriad artistic inspirations, from textiles to architecture to the color palette of 15th-century Florentine painter Fra Angelico and the labyrinthine visual networks of computer hardware.

This is an exhibition worth seeing for all of the right reasons. Whether your interest is technical, aesthetic or historical, Schwarcz’s work will have you entranced.