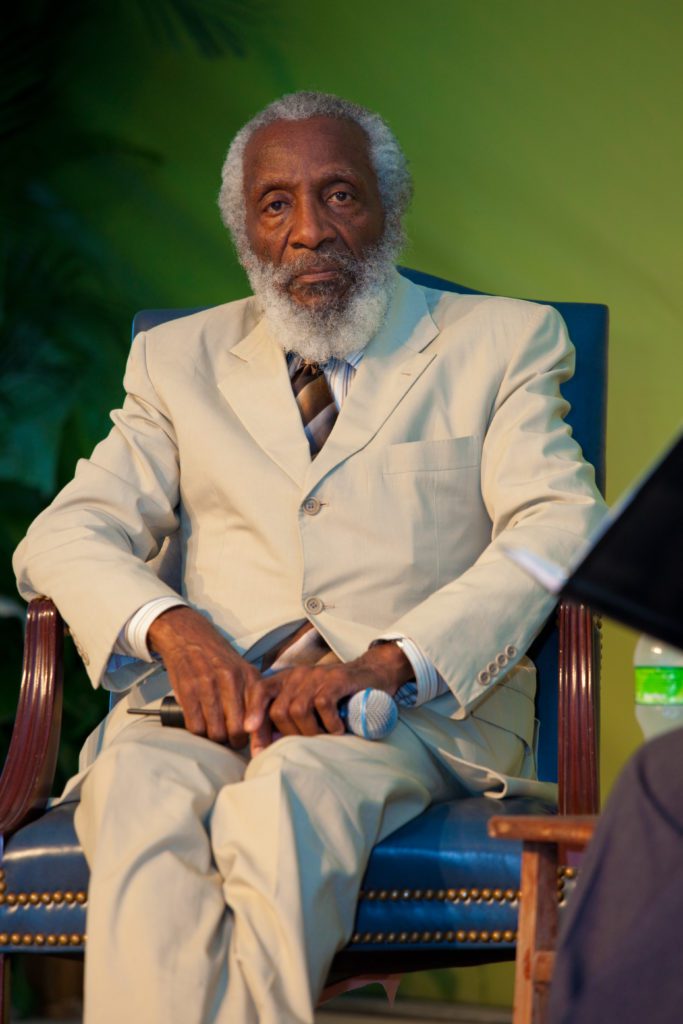

A Fallen Tree: The Life and Times of Dick Gregory

By • August 22, 2017 One Comment 3893

“A tree has fallen. The leaves you left behind will forever be in the wind.”

On August 19, comedian, activist and nutritionist, Richard Claxton “Dick” Gregory left this earth after a brief illness.

I was blessed to have been with him an hour before he left us. Thirty minutes after I arrived home, my telephone rang. Nothing prepared me for E. Faye Williams’s voice saying, “Dick is gone.” I felt what he always referred to as a shift in the universe. The feeling that something fell in my life that would never be lifted. Before going to bed, I wrote “A tree has fallen. The leaves you left behind will forever be in the wind.”

I had known Dick Gregory since 1992, when we met in St. Louis, Missouri, at a conference. We talked often. Writing his memoirs would turn my time with him into a classroom about history, the civil rights movement and nutrition.

Now, he is gone. I didn’t know how to stop grieving and be the storyteller of his life that he entrusted me with for 25 years.

His life was so big and he had touched so many people that it was hard for me, even as his biographer, to write this article.

I realized that the little black boy born to Lucille and Presley Gregory in 1932 in St. Louis was no ordinary man. He was no ordinary child. He survived a childhood plagued by poverty. He had learned to tell jokes on the playground to block bullying from children he wanted to befriend. Gregory excelled at track at Sumner High School, and he was his senior class president. He went on to earn a scholarship to Southern Illinois University, where he set school records as a half-miler and miler. But heartbreak would come when his mother died his freshman year in college. Before he could adjust to losing her, he was drafted into the United States Army.

It was the army that would prove to be his new stage for comedy. After Dick fooled around a time too many, his colonel forced him to enter several talent shows where he found laughter with his jokes.

When the army released him, he went back to Southern Illinois for a brief time, then set off to find his brother Presley in Chicago. He found a job working in the post office, but he never stopped looking for jobs in night clubs. He began working in clubs around town, including the Esquire and the Roberts Club. One night while performing he met a woman named Lillian Smith, whom he would marry and spend the rest of his life with.

He now had a new wife and a child on the way. So, he opened a new nightclub to try to make it on his own and earn more money for his growing family. After the failure of his club, he returned to the Roberts Club where he was spotted by Hugh Hefner one night. Weeks later, when comedian Irwin Corey failed to show up at the Playboy Club, Hefner called Dick Gregory. The stage manager warned Dick not to go on because a bunch of white Southerners were in town for a convention and filled the audience that night. Dick walked on stage and turned the jokes on them.

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, I understand there are a good many Southerners in the room tonight,” he said. “I know the South very well. I spent 20 years there one night.”

He continued: “Last time I was down South, I walked into this restaurant and this white waitress came up to me and said, ‘We don’t serve colored people here.’ I said, ‘That’s all right. I don’t eat colored people. Bring me a whole fried chicken.’ ”

“Then, these three white boys came up to me and said, ‘Boy, we’re giving you fair warning. Anything you do to that chicken, we’re going to do to you.’ So, I put down my knife and fork, I picked up that chicken and I kissed it. Then I said, ‘Line up, boys!’ ”

The men laughed all night and that night would open the door for Gregory to appear on “The Jack Paar Show” and other national television shows. It also opened the door of fame and wealth for Dick and his family.

He had no idea that his life was about to change again — and forever — when Medgar Evers asked him to come to Jackson, Mississippi, to march with him. Mississippi and other states in the deep South were in the throes of a traumatic movement to end violence and oppression by white Americans against black Americans. That was the turning point for the man who would continue marching for 60 years.

After Evers was murdered, Gregory became more active in the civil rights movement. He marched with Dr. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, and he often went alone. He was arrested more than 100 times and shot in the leg during the riots in Watts. Gregory often skipped engagements because he felt the movement needed him more. By now, he was losing millions and agents were calling on other comedians to replace him. He marched on!

By 1967, Gregory realized that he needed to be on the inside to help people who could not speak for themselves and he decided to run against Richard J. Daley for mayor of Chicago. He lost, but his campaign set the stage for him to run for president of the United States in 1968 as a write-in candidate of the Freedom and Peace Party. His running mate was Mark Lane, now deceased.

His campaign was interrupted when King was assassinated in 1968. With his wife, Lil, Dick went to the funeral in Atlanta and vowed to continue his fight for justice in America. He lost the election but Gregory did not lose his commitment to help change the world. He and Lane also wrote a book called “Code Name Zorro” about King’s death. Zorro was the FBI code name for King.

While on a hungry strike against the Vietnam War, Dick began to study nutrition and would later create the Bahamian Diet. This diet was a huge success in the early years and he earned millions, but he never stopped protesting and standing up for the people who did not have a voice. When the company failed, Gregory went back to what he did best, comedy and speaking engagements that were not always what the media deemed popular.

The world was changing, but Dick Gregory never stopped marching to correct what he felt were injustices.

In 1999, he discovered he had cancer, but he beat the disease and stayed on a diet that included herbs and special teas until the day he died.

In his life time he wrote more than 20 books, including, “Write Me In,” “Callus on My Soul,” “Nigger” and “Up From Nigger.” He was in several movies and continued to do speaking engagements and comedy until three weeks before he became ill.

In early August, as summer started to turn into early fall, Dick was hospitalized for a bacterial infection. His wonderful wife of 59 years and their 10 children rotated standing by his bedside until the end.

His final hours proved that he really was a soldier. There was no fear in the eyes of my greatest teacher. There was no sign of struggle. He knew his work on this earth was finished. He had fought the good fight!

Now he is with Medgar, Malcolm and Fannie Lou Hamer. He is face to face with Dr. King and all the soldiers that we lost on the battlefield.

For those he left behind, the world seems a little smaller now. The sun is not as bright. It is my hope that those who knew him and the strangers to who yelled “Hello and God bless you” to him on the street will pick up the torch and carry on this battle called life.

It is my belief that his grave will be empty. He left everything here on earth for us to learn from. Good night, Dick Gregory!

Shelia P. Moses is a writer, producer, poet and Dick Gregory’s biographer. She co-wrote his last memoir, “Callus on My Soul.” Her latest book is a children’s book about Dick Gregory, titled, “Fire, The Dick Gregory Story.” Visit Mosesbooks.org for more details.

I had a chance to see Mr. Gregory once about 1968 or 69 at the University of Oregon, when I was student there. He was amazing!