Adding to the List of Those We Miss

By • September 25, 2017 0 584

People die all the time — just ask Wikipedia.

In the course of a year, in the course of a month, that’s where you find the dearly, mysteriously departed, like clockwork: name, age, occupation, notability, what he or she succumbed to, the people and work and achievements left behind.

Depending.

Not everything is there. Intimate knowledge, color of hair, for instance. It’s a Joe Friday kind of thing — just the facts, ma’am.

Of course, when rock stars, presidents, the mothers of presidents, Nobel Prize winners or high members of the nobility elude us, we notice. But there are times when less-famous folks pass on and we miss the chance to salute them, to express our appreciation. Baseball Bill Holdforth, for instance, the city’s supreme baseball fan, Hawk ’n’ Dove bartender and raconteur died this past June, and the former owner of that very same Capitol Hill pub died last September.

We went through the month of September, adding to the list of those we miss. Such selections, when someone does them, are almost always personal as well as historical, leaning towards our special interests — for me, books of all kinds and their authors, sports figures, poets, singers, pop stars, actors, criminals of note, celebrities, personal contacts, even animals (like Eddie, the cantankerous star dog imbedded in “Frasier”). Or, sometimes, people are just interesting, a nagging absence or presence, or they spark a memory or are connected by frayed strands of commonality.

Most recently, the thin, but thick-with-stories actor Harry Dean Stanton passed at 91, having lived a movie-theater-cult life of amazing strangeness. He looked in his pictures like a man about whom every story ever told or written is true, no matter how odd. He was also a gifted actor who when you saw him — in westerns, often, in indie films or in cult classics (he outweirded William Dafoe in “Wild at Heart” and “The Last Temptation of Christ”). His Kentucky parents were a cook and a tobacco farmer and barber. Here are the films, some of them: “Pretty in Pink” (honest to god and everyone else), “Cockfighter,” “Tomahawk Trail” and, most famously, “Paris, Texas”). I saw him recently in “The Missouri Breaks,” in which he was killed by a lawman played by Marlon Brando wearing a dress. He also toured in nightclubs, singing and playing a guitar, and, of course, he was in “Twin Peaks.”

Don Williams — he died at 78 in September — looked like a country music star and sang like a man who had a permanent scar, which translated into beautiful, simple-as-an-arrow love songs, hardly the stuff of contemporary back-of-the-truck swains. He wore a scruffy cowboy hat that looked like it was bent 68 ways and needed washing, along with a blue-jean jacket, a hat and boots.

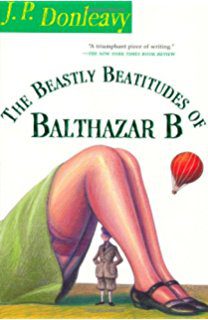

Sometime this month, as I went through my books, I ran across “A Singular Man” and “The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthazar B,” lyrical novels by a man named J. P. Donleavy, who became famous and rich by writing what was considered a dirty book, called “The Ginger Man,” which I do not have. He died at 91 at his sprawling — no doubt cool and cool-Irish estate, where he resided for years and years, not writing much lately. His books were often riotously funny, epigrammed to within a type-set inch of their lives and sharp as a slap, a nail or unwarranted luck, as well as a bill that’s unavoidably due and accurate. Or as in this sentence: “My finger dips into the cold indelicacy of Dublin.” He had a splendid beard and a walking cane.

If Don Williams in his way, and Donleavy in his way, could be counted as poets, John Ashbery was the poet in the land. He won every award, was considered — these days — America’s finest and was part of a rich generation of artists centered around New York that included poet Delmore Schwartz, Pollock, Lichtenstein and so on. Before all things happened to New York, all things were happening in New York. Ashbery was one of them, along with his wit. “Just when I thought there wasn’t room enough for another idea in my head, I had this great idea.” “The first year was like icing, then the cake started showing through.” He won the Pulitzer Prize for “Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror.”

And so we come to Jake LaMotta, of whom, for me, there are two things. First: “Raging Bull,” the scathing black-and-white movie directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci. De Niro pumped up to Pillsbury size. Second: watching middleweights fight on Friday Night Boxing with my stepfather, including the silky Sugar Ray Robinson. Though LaMotta was battled into an unrecognizable form, he was never counted out.

Lillian Ross, the elegant writer of profiles for the New Yorker, whose best was probably a print realization of J. D. Salinger.

Edith “Edie” Windsor, an LGBT-rights activist who was the lead plaintiff in United States v. Windsor, which successfully overturned Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act, the landmark legal victory of the same-sex-marriage movement.

I remember Bernie Casey from my college days. He was the star running back of the 1960-61 season at Bowling Green State University, and from that built a successful television and movie career. One of his pictures — “Guns of the Magnificent Seven” — I saw recently on the Encore Western Channel. He died in September at 78. I remember him, running free, big and powerful on a sunny fall afternoon in a packed stadium in Ohio, probably also in September.