‘The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address’ A fact-filled (if less-than-scintillating) primer on D.C.’s riverside complex

By • May 16, 2018 0 476

Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

Hotels can intrigue, even captivate. In the pantheon of places, nothing tantalizes so much as a good story situated in a hotel, particularly a luxury hotel with hot- and cold-running bellhops, genuflecting valets and chandeliers that drip with crystal. Think the Metropol in “A Gentleman in Moscow” by Amor Towles.

Built on superstition, few hotels have a 13th floor — most elevators go from 12 to 14 — but each floor can hold secrets, whether dreadful or delightful. As such, hotels have been the subject of movies (“Grand Hotel” with Greta Garbo, “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” with Judi Dench), novels (“Hotel Du Lac” by Anita Brookner), children’s books (“Eloise at the Plaza” by Kay Thompson), a rollicking BBC television series (“The Duchess of Duke Street,” the story of the king’s mistress, who owned the Cavendish Hotel in London) and even an Elvis Presley classic (“Heartbreak Hotel”).

Hotel sites beguile, possibly because they provide escapes from the real world and adventures for the escapees, which translates into vicarious pleasure for the rest of us.

Whether fact or fiction, the standard recipe for a good hotel story contains basic ingredients:

1 lb. scandal

1 cup sex

2 cups eccentric guests

1 dash crime

1 pinch skullduggery

For added spice, mix in two cups of chopped celebrity and bake for 350 pages. Voilà! You’ve got the perfect hotel-story soufflé.

Joseph Rodota followed this recipe to write his first book, “The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address.” For scandal, crime and skullduggery, he provides the 1972 burglary in the Watergate office building of the Democratic National Committee, which led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon, which, in turn, spawned a great film, “All the President’s Men.”

For eccentricity, Rodota showcases Martha Mitchell, wife of Nixon’s attorney general, and her midnight phone calls. Freshly sprung from a psychiatric ward in New York to move to Washington with her husband after Nixon’s inauguration, Martha soon gave hilarious definition to drinking and dialing. Belting back bourbon late at night, she frequently called Helen Thomas, UPI’s White House correspondent, to unload on “Mr. President.”

For eccentric good measure and a smidge of sex, Rodota tosses in the Chinese hostess (cue Anna Chennault) who served “concubine chicken” at dinner parties in her Watergate residence.

From John F. Kennedy to John Mitchell to the johns who paid for prostitutes, this book drops more names than a prison roll call. With the exception of Monica Lewinsky, who, in the 1990s, lived in her mother’s Watergate apartment — where she hung the blue dress that led to the impeachment of President Bill Clinton — most of the dropped names are Nixon-era Republicans: Elizabeth and Bob Dole, Rose Mary Woods, cabinet members like Maurice Stans, John Volpe and Emil “Bus” Mosbacher.

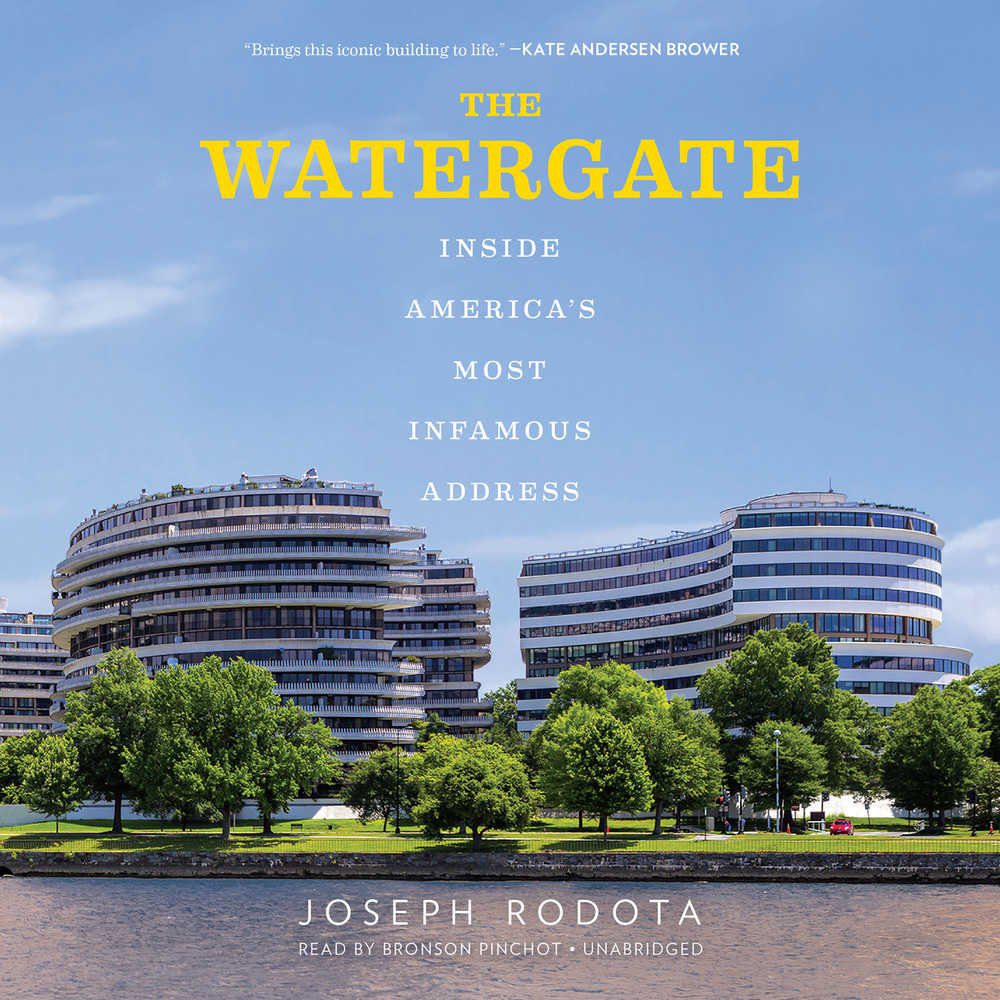

With skillful research from old newspapers and magazines, oral histories from presidential libraries and a few interviews, Rodota has fashioned an interesting story about the white concrete edifice that looks like a giant clamshell. With three buildings of wraparound co-op apartments terraced with egg-carton balustrades, the Watergate, facing the Potomac River, sits adjacent to the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

To tell his story from the beginning, Rodota burrows into the complicated bureaucracy that surrounds any major construction project in the nation’s capital. He whacks through the weeds of proposals and counterproposals from the financiers, architects and developers to the National Capital Planning Commission, the D.C. Zoning Commission, the National Park Service, the Commission on Fine Arts, the committee overseeing the National Cultural Center (later named the Kennedy Center), Congress and, finally, the White House. All had to reach agreement before a shovel broke ground.

Beginning in 1962, numerous hearings were held to discuss plans for Watergate Towne, a complex that would include a gourmet restaurant, a spa, a beauty salon, a grocery store, a liquor store, a cleaners, a florist, a bakery and a designer boutique. Still, there was concern, especially over the project’s financing and what the Kennedy White House called “the Catholic problem.”

As the first Catholic to be elected president — and only by 100,000 votes — John F. Kennedy knew his religion was problematic to many. As president, he genuinely wanted to make Washington “a more beautiful and functional city,” which the Watergate project promised to do. But he would not sign off on the $50-million proposal because it was largely underwritten by the Vatican, then the principal shareholder in the development company Società Generale Immobiliare.

The formidable columnist Drew Pearson stoked controversy over “popism” with a syndicated column headlined: “Vatican Seeks Imposing Edifice on Potomac.” A group called Protestants and Other Americans United for Separation of Church and State mobilized its members.

Within weeks, the White House received more than 3,000 letters opposing construction of the Watergate and, according to one, “having Miami Beach come to Washington.” Most voiced outrage that Kennedy would be under clerical pressure to do the bidding of “the world’s richest church.” The Vatican soon divested its interest in the project, and, by Nov. 22, 1963, most objections were muted.

Probably because there is no breaking news in Rodota’s book, his publisher sent a letter to editors and producers trying to burnish the fact that “The Vatican, the coal miners of Britain, and Ronald Reagan have something in common: They each owned a piece of the Watergate. Ronald Reagan held a financial stake in the Watergate complex shortly before becoming president, a fact that has never been made public before this book.”

Wowza! Stop the presses!

Yet the author does a good job of mixing historical facts with personal anecdotes to tell the story of what was both the most famous and most infamous hotel in Washington, D.C., until the presidential election of 2016. Perhaps Rodota will follow this book with another hotel story titled “Tales from the Trump International,” which might indeed provide some needed wowza.

Among Kitty Kelley’s many books is “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys.” In two 1988 cover stories for People magazine, Kelley broke the story of Judith Exner’s confession that, in addition to being JFK’s lover, she was also his conduit to the Mafia, carrying his messages to Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana.