Sculptor Alberto Giacometti spent most of his artistic life in a 15-by-16-foot studio on Rue Hippolyte-Maindron in Paris’s Montparnasse district. A film clip running continuously in the exhibition “Giacometti” — on view through Sept. 12 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum — shows the Swiss-born artist at work in the confined and cluttered space, a few years before his death in 1966.

Listening to this weathered and intense adoptive Parisian answer questions in French as he works (his comments are then translated into English), the viewer understands why the tiny studio, which Giacometti first occupied in 1926, has been metaphorically described as his shell and cranium.

It is now privately owned. But last month, the Paris-based Giacometti Foundation, which collaborated with the Guggenheim on the New York retrospective, opened a recreation of the studio, complete with dirty ashtrays, within the new Giacometti Institute on Rue Victor Schoelcher, a short walk from the original. The institute’s inaugural exhibition, “The Studio of Alberto Giacometti Seen by Jean Genet,” runs through Sept. 26.

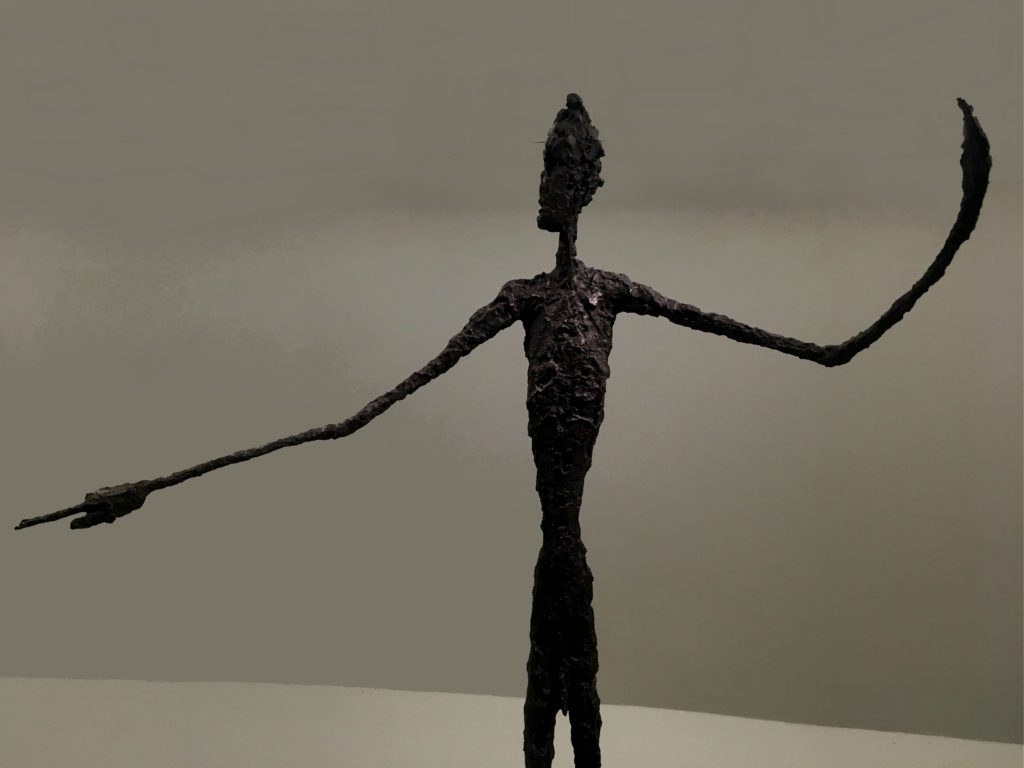

Giacometti’s signature works are his rough-surfaced, uncannily expressive stick figures of the late 1940s, tooled (and thumbed) in clay and cast in bronze. With their extra-long limbs and, with some exceptions, oversized heads, hands and feet, they almost immediately became universal symbols of 20th-century existential angst. Among those on display are components of an abandoned public art commission for Chase Manhattan Bank in Lower Manhattan; the inconclusively provocative “Man Pointing”; and “City Square,” a mini-composition of oblivious striding figurines.

Two of the figures in the show are on wheeled bases, said to be inspired by a hospital cart, an Egyptian battle chariot or both: “Woman with Chariot,” in plaster and wood, and “The Chariot,” in bronze, which brings to mind David Smith’s welded “Voltri VII” of 1962 in the National Gallery of Art (Smith was just five years younger than Giacometti).

The exhibition also features early works influenced by Brancusi, by Cubism and by encounters with Egyptian, Cycladic, Oceanic and West African sculpture. And several of Giacometti’s Surrealist masterpieces of the early 1930s are here, including “Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object),” “Suspended Ball” (a bleak anti-mobile made around the time that Calder began to create his playful ones) and, borrowed from the Museum of Modern Art, “Woman with Her Throat Cut,” no less obscene for being semi-abstract.

“The Nose” of 1949, a gruesome Pinocchio head hanging from a wire in a cage-like frame, merges Giacometti’s Surrealist and figural styles. The image apparently arose from nightmares, connected with the death of a traveling companion, that Giacometti had upon returning to Paris after World War II.

At the start of the war, Giacometti had gone to visit his mother in Switzerland and was not allowed to return to France. During those years, he made miniature busts, also in the exhibition, which served as a transition to his larger figural work.

In creating his figural sculptures and his dense, Francis Bacon-esque frontal portraits, painted mainly in blacks, grays and browns (the show includes quite a few), Giacometti returned again and again to the same models, especially his wife Annette and his brother Diego. In the film clip, he says that, even if a model sat for a thousand years, the result would still fall short, though the effort would be worth making.

Outside the screening room, at the top of the Guggenheim’s spiral ramp, is a minor masterpiece, “Dog” of 1951, from the Hirshhorn Museum. It is as if a laundry-marker sketch of a nearly starved gutter hound had been 3D printed. There is also reason to call it a self-portrait. A label notes that Giacometti told notorious novelist and playwright Jean Genet: “One day, I saw myself in the street like that. I was that dog.”

The Guggenheim is closed on Thursdays and has late hours on Tuesdays (until 9 p.m.) and Saturdays (until 7:45 p.m.; pay what you wish after 5 p.m.).