Almost every obituary, story and tribute that emerged in the aftermath of Tab Hunter’s death on July 8 at age 86, of cardiac arrest resulting from a blood clot, touched on the tensions and themes of his life in short order.

Heartthrob and teenage idol, movie star, singer (yes, singer) and gay icon — plus adjectives such as hunk, blonde, blue-eyed, tall, handsome — were used to describe him by movie publicists, scandal mags, critics, admirers and those who, not without a little envy, did not much admire his acting skills.

The references in some ways didn’t begin to touch on the episodic and improbable variety of stories in his life, which resembled a kind of tug of war lived simultaneously in a house with too many rooms, in which the public and private lives were conducted — the one strung to the other as a price exacted by fame and life in the spotlight.

The news of his death was announced by his longtime companion and spouse Allan Glaser, a fact which tells you how far Hunter, who had a big Hollywood studio career, had come in his acknowledgement of his sexuality. It was not until his autobiography, “Tab Hunter Confidential,” was published in 2005 that he openly confronted and dished about his being gay, in typical Hunter and Hollywood fashion.

The title itself referenced a long-gone Hollywood scandal mag and rag that specialized in drug and sex scandals and outing stars (see Robert Mitchum’s drug bust for marijuana use). Back in the 1950s, when Hunter was a rising-and-getting-bigger star at Warner Bros., the magazine published a story that he attended a gay party.

Hunter fretted that it would ruin his career. It didn’t. Studio head Jack Warner just ignored the story — this was often the fate of Confidential stories, along with lawsuits — and the story soon faded away.

Hunter stood tall in the imagination of his audience, mostly young women, but also the type of guys who like war movies and Westerns, still mainstream movie fare in the 1950s. He starred in or was a significant part of such films as “They Came to Cordura,” “The Sea Chase” and “Gunman’s Walk.” This was after Hunter, whose mother was a strict Catholic German immigrant, was discovered working in a Los Angeles horse stable, which eventually led to a lifetime passion for horses.

In the 1950s, he was hot, physically and at the box office. He was perpetually seen squiring beautiful rising starlets around town, a fairly common thing among some closet gays (Rock Hudson married his secretary, after all). He was seen with Natalie Wood a lot; he starred with her in the Western “The Burning Hills” and “The Girl He Left Behind.” But his role in a big Warner epic, “Battle Cry,” based on the best-selling novel by Leon Uris and directed by Raoul Walsh, drove him to the top as icon and heartthrob. He played a young and heroic Marine who briefly falls for older woman Dorothy Malone, then returned to his high school sweetheart, played by Mona Freeman.

Although he insisted he was no singer, he recorded “Young Love,” which supplanted Elvis on the top of the hit parade for a time, although the original version by country music star Sonny James is much the better song.

Finally, age — more than the perpetual personal conflict, which included a relationship with Anthony Perkins of “Psycho” fame — seemed to put an end to the spotlight, even with intermittent roles in films like “The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean” with Paul Newman.

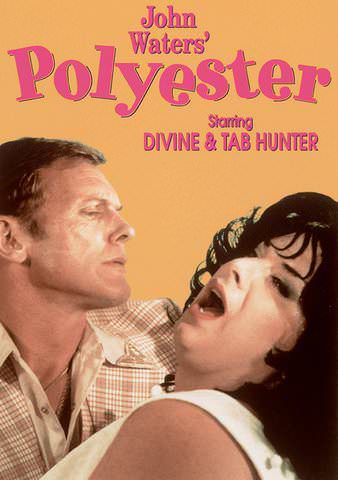

And then came “Polyester.”

“When I saw the script, I laughed out loud,” Hunter wrote. The 1981 film was the work of iconoclastic writer and director John Waters, Baltimore’s very own legend, a one-man fringe festival. Hunter accepted a role in the movie, in which he played the operator of a drive-in movie theater specializing in foreign and art-house films, serving wine and French food.

His agent, according to Hunter, warned him that “making a movie with a transvestite” — namely Divine — “was career suicide … don’t do it.”

Hunter did it anyway, courting Divine, who played a love-starved housewife with a suicidal dog. Waters had asked him if he would object to kissing a transvestite and Hunter recalled that he responded: “I’ve probably kissed worse.”

The movie, complete with sniffing cards, was a hit, especially in Georgetown. The late Key Theatre proprietor David Levy, who also founded the Biograph, proposed an old-fashioned Hollywood premiere.

We came for the show. Divine — normally a big guy in a black T-shirt and slacks — dazzled in a bouffant blond wig and a tight spangled dress that seemed to shine for miles around, accompanied by spotlights that rose spectacularly into the night sky. It was like Oscar night on Wisconsin Avenue — unforgettable.

Hunter called it his best role ever.

“Polyester” was a noteworthy comeback, and it seemed to settle the restive Hunter into accepting himself. He understood the Hollywood-created dilemma. A practicing Catholic on his own terms, he said he felt then that if he went with men, he was sinning, and if he went with women, he was lying.

It seemed, at the end, that Hunter had sorted things out, made sense of his life, without blame or rancor. He could laugh about his life, as when he was often mistaken for Troy Donahue, another Hollywood heartthrob with similar looks. “Sometimes,” he wrote, “I would even agree to be him, just for the hell of it.” One senses that he knew exactly who he was and treasured his life, looking back and living it with his spouse, the troubled parts accepted and woven into the whole.