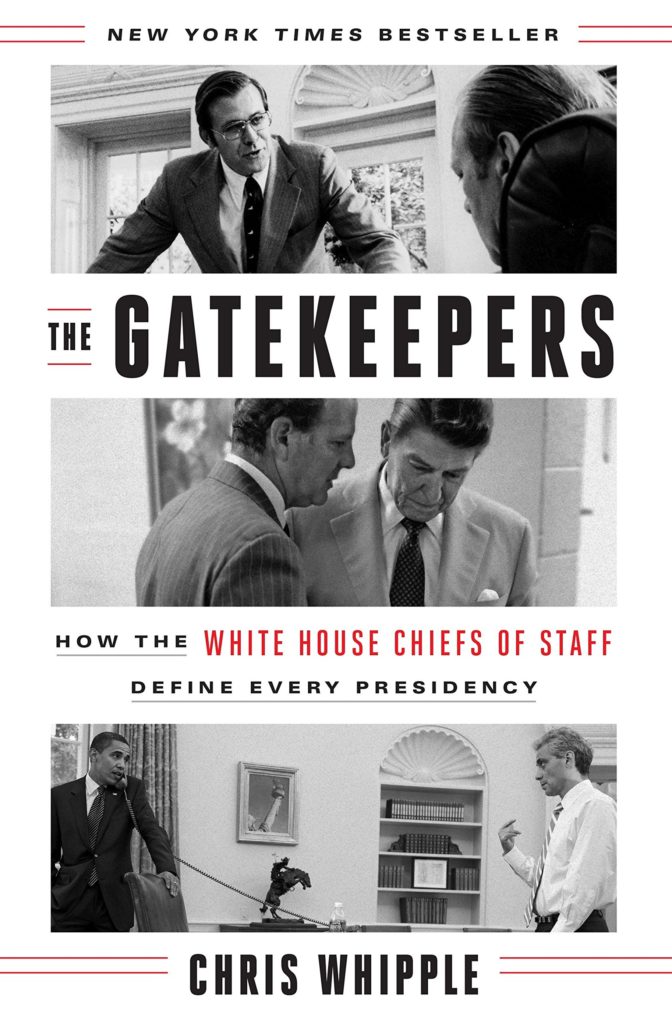

‘The Gatekeepers: How the White House Chiefs of Staff Define Every Presidency’

By • August 8, 2018 0 1456

Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

Meet the powerful men behind the powerful man. Political junkies will cartwheel into line to grab copies of “The Gatekeepers: How the White House Chiefs of Staff Define Every Presidency” by Chris Whipple.

They might not be as mesmerized as they were with “The Making of the President”by Theodore H. White or “What It Takes” by Richard Ben Cramer, but they’ll have inhand a bible on presidential sons-of-bitches. That’s how H.R. Haldeman defined theposition before he had to resign and go to prison as one of 48 people who served time for serving Richard M. Nixon.

The White House chief of staff is considered the most powerful unelected person in Washington, D.C., because he — there’s never been a she — controls access to the leader of the free world. As the president’s main adviser and closest confidant, thechief of staff determines the administration’s legislative agenda and communicates with Congress and the Cabinet. He is the spear catcher who protects the president from all incoming flak.

“The White House chief of staff has more power than the vice president,” said Dick Cheney, who should know. At 34, he served as chief of staff to Gerald Ford. By the time he turned 70, Cheney was vice president to George W. Bush and knew how to mow down chiefs of staff Andrew Card and Joshua Bolten. Known by some as “Darth Vader,” Cheney controlled foreign policy in the Bush years and seemed to assume as much power as “the decider” himself.

“Every president reveals himself by the presidential portraits he hangs in the Roosevelt Room,” said historian Richard Norton Smith, “and by the person he picks as his chief of staff.”

By that definition, Whipple could have produced an intriguing analysis of Ronald Reagan, who chose the smooth-talking Texan James Baker III as his first chief of staff, followed by the bullheaded Donald Regan, who compared his job to the man in the circus, sweeping up elephant droppings.

Unmentioned by Whipple was John Roy Steelman, the first and longest-serving chief of staff, described in his New York Times obituary as a “onetime hobo from Arkansas.” Serving from 1946 to 1953, Harry Truman’s chief of staff was as basic as the man he served. Eschewing his powerful title, Steelman preferred to be called “the president’s chief chore boy.” His biggest chore was his role in ending a 52-day strike by steelworkers, one of the most damaging stoppages in U.S. history.

“The Gatekeepers” promises to offer “shrewd analysis and never-before-reported details,” but there appears to be little of either in the book. Perhaps Whipple was too grateful for his access to cast a critical eye and dig beneath the glossy surface.

All those interviewed protected their presidents from incriminating revelations, but each agreed that being White House chief of staff was the toughest job he ever tackled. The pressure is so great that few last beyond 18 to 24 months.

The major takeaway from Whipple’s book is not unlike Cardinal Cushing’s advice to John F. Kennedy when he first ran for office in Massachusetts: “A little more Irish … a little less Harvard.”

The most successful sons-of-bitches are a little more staff … a little less chief. In fact, certain chiefs — Gov. Sherman Adams, who served Dwight Eisenhower; Gov. John Sununu, who served George Herbert Walker Bush; and the aforementioned Don Regan, who was CEO of Merrill Lynch — harmed their presidents by their inability to shed their arrogant prerogatives of self-entitlement. All had previously held chief executive positions, but each was fired from his role as White House chief of staff.

Usually, an author writes a book and hopes to sell television rights after publication, but Whipple, an award-winning producer at “60 Minutes” and “Prime Time,” did itthe other way around. He provided the interviews for the four-hour documentary“About the Presidents’ Gatekeepers” that aired on the Discovery Channel in 2013. The interviews he did with the 17 chiefs of staff alive at the time became the basis of “The Gatekeepers,” his first book.

Whipple’s text hardly inspires, but his chapter notes pique interest. Many of those cited (again, mostly men) hiss and spit at each other like cats being hosed. Ed Meese III dumps on Jim Baker III for leaking to the press. Donald Rumsfeld, chief of staff to President Ford, disses White House speechwriter Robert Hartmann as an alcoholic, and says Ford’s vice president, Nelson Rockefeller, “wasn’t qualified to be vice president of anything.”

Leon Panetta, chief of staff to Bill Clinton, confides that the president wanted to fire George Stephanopoulos. This was seconded by Erskine Bowles, who followed Panetta: “Of course, George was cut out by the President.” Colin Powell and Brent Scowcroft slam Cheney, who, in turn, stomps on the claim of CIA Director George Tenet about bringing the danger of al-Qaeda to White House attention. “I do notrecall George coming in with his hair on fire.”

The most intriguing chapter note cites an interview with Stuart Spencer, the Republican political consultant, who speculates about how President Reagan might have unwittingly approved the Iran-Contra operation to secretly sell arms to Iran and funnel the money to support the Contras in Nicaragua.

“I can see those three guys [National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane; National Security Council Deputy Director Oliver North; and CIA Director William J. Casey, who, according to Spencer, was called Mumbles]. They knew that Reagan was in favor of the contras; he was really upset about the American hostages; and they said,‘We’ll take advantage of that.’ And they sent Mumbles over to tell him about it. AndReagan didn’t have his hearing aid on! I believe all this could have happened.”

Stuart Spencer was extraordinarily close to the Reagans for years. He ran Reagan’s successful campaigns for governor of California in 1966 and 1970, as well as his campaigns for president in 1980 and 1984. He counseled both Ronald and Nancy Reagan throughout their eight years in Washington, and was one of the few people invited to accompany them on their return flight to California upon leaving the White House in 1985. So his speculation about Iran-Contra deserves more scrutiny, especially because the first lady was terrified the matter would lead to her husband’s impeachment.

Did Whipple ask Spencer whether he discussed Iran-Contra with either Reagan? If he didn’t, why not? How did the subject of Iran-Contra come up in his interviews with Spencer? Did Spencer advise the Reagans about Iran-Contra? What was his recollection of how they coped with the matter personally? Did Spencer share his theory with the first lady or anyone else?

Note to Whipple: a little more time with Stu Spencer … a little less time with the chiefs.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.”