Last Chance: ‘Nordic Impressions’ at the Phillips

By • January 8, 2019 0 924

Author’s note: The government shutdown is having an ongoing effect on the majority of Washington’s art museums. The Smithsonian and the National Gallery of Art receive federal funding, and as such will be closed until the government reopens. If the shutdown extends through The Georgetowner’s next issue, I will discuss it at that time. Fortunately, there are still many museums that remain open, in addition to many galleries: the Kreeger Museum, the National Building Museum, the National Museum of Women in the Arts and the Phillips Collection, to name a few. Let’s give them our attention and support.

In my limited encounters with Nordic art, it has struck me as surreal the way it runs a parallel yet slightly alternative course to the European canon. The aesthetic of the Nordic countries coincides with that of their southern neighbors, and yet it does not dovetail that cleanly. There are fissures, ripples of divergence in these Nordic works, that have always reminded me of old science-fiction plots about parallel universes, but as they might correspond to modern art.

Step through a wormhole and into a world where the subdued color palettes and soft forms of Victorian England and America achieved influence equal to the bold, aggressive technicolor of the Fauvists.

Perhaps this is nothing more than a game of connect-the-dots, art history edition. Making visual connections across history, as well as between individual artists, is one of the great joys of art appreciation. More often than not, this is a useful exercise, because artists themselves have always played this game directly on their canvases.

So it would stand to reason that Nordic artists, connected to the rest of Europe yet isolated enough to develop unique strains of style, would produce work that walks a line between the foreign and the familiar.

At the Phillips Collection through Jan. 13, “Nordic Impressions” introduces audiences to the artistic achievements of Nordic painters. Featuring many works never before seen in the United States, the exhibition includes works by 53 artists spanning nearly 200 years.

Opening the show, Helmer Osslund’s painting, “A Summer Evening at Lake Kallsjon,” c. 1910, feels almost like a Rockwell Kent, with sharp light and billowing clouds against an abruptly shifting landscape of light and dark. It sets the tone of a stark, grandiose horizon that reflects a sort of riveting quietude.

Osslund is an appropriate segue into Nordic art. He studied with Paul Gauguin in Paris, seeking to blend visual impressions of nature with his own feelings in a style characterized by flat areas of color and bold outlines inspired by Japanese woodcuts. When he began painting the landscapes of Sweden and Norway — especially the snow-covered mountains and vivid green mosses growing in the chalky soil of the Nordic peninsula — he found a truly distinct voice.

Three other early paintings stand out: Christian Krohg’s “Braiding her Hair” of 1888, Harriet Backer’s “Evening Interior” of 1890 and Elin Danielson-Gambogi’s “Self-Portrait” of 1903. Khrog, one of Norway’s most renowned artists, had an eye for simple everyday moments. His technique is reminiscent of Edgar Degas or Mary Cassatt, but with a distinctively Nordic psychology that conveys the emotional seclusion that the region seems to breed. The composition looks on from behind its subjects, their faces unseen while they work with steady focus on the task at hand. These subjects are not daydreamers.

Danielson-Gambogi’s self-portrait, though small, is one of the strongest paintings in the exhibition. It has a distinctive connection to the English and American art of the day, like James McNeill Whistler or Abbott Handerson Thayer. It seems the fog, mist and frost of both England and New England offer a tonal harmony with the Nordic atmosphere.

Midway through the exhibition, a fine collection of Munch prints offers an intriguing tie-in to the wider European art scene, if only at a brief glance. It is an important and necessary nod, while not overplayed.

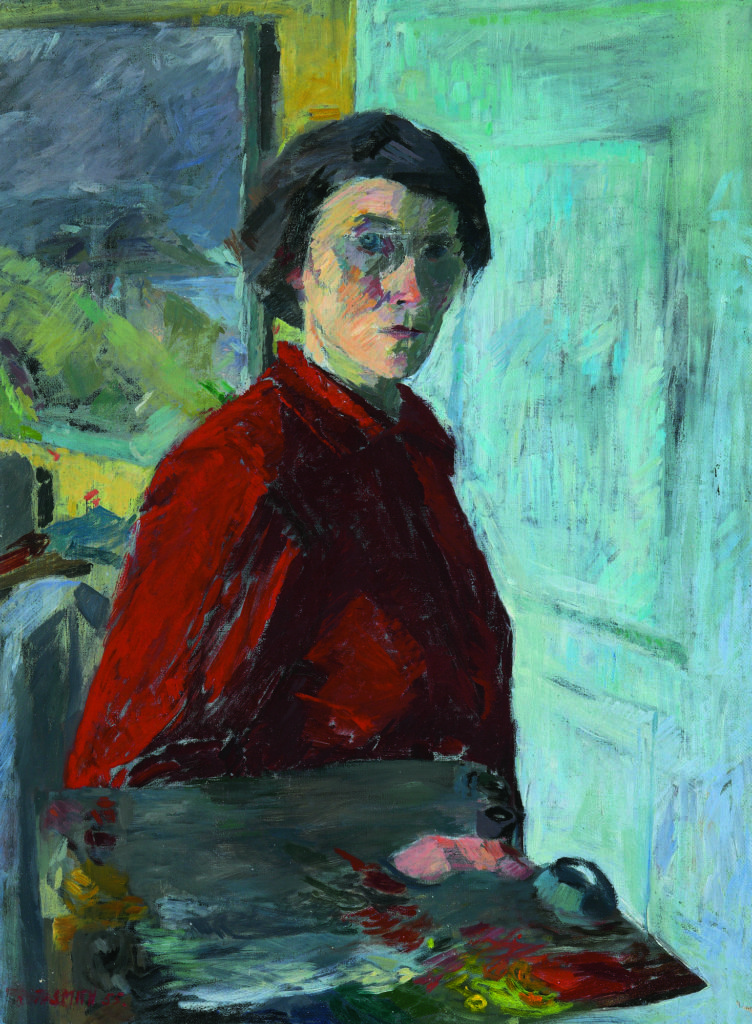

Moving deeper into the 20th century, Johannes S. Kjarval’s “Warrior Maiden” of 1964 and Ruth Smith’s “Self-Portrait” of 1955 together offer a vision of art’s divergent evolution. The works of Kjarval, a towering figure in Icelandic art, exhibit early Icelandic interpretations of Futurism and Cubism, exploring the mythology of the area. “Warrior Maiden” is like folk art by way of Adolph Gottlieb. Meanwhile, Ruth Smith’s self-portrait could be a portrait by Paul Cézanne or even Elaine de Kooning.

Incidentally, 19th– and 20th-century women artists are represented to a greater extent in this exhibition than in any other survey I’ve seen that wasn’t focused specifically on women. Whether this is due to Scandinavia’s unique breed of social progressivism or a mission of the curators, it was a breath of fresh air.

The postmodern and contemporary art on display leaves the door wide open. From Pia Arke’s video “Arctic Hysteria” of 1996 to Outi Pieski’s hanging installation of wood and thread, “Crossing Paths” of 2014, to paintings by Per Kirkeby and Tal R, there are endless dots to connect, to and from Henri Matisse, German Expressionism, postmodern European performance art, the contemporary craft revival and so on. The point is, perhaps, just how global, diverse and connected our world has become, no matter how geographically isolated one may be.

To that end, if you’d asked me last week what I knew about Nordic culture, I’d have probably made references to Munch, gravlax, the Faroe Islands, bleak independent films, blond hair and maybe elk hunting. Now I’m happy to be able to point to this exhibition and admit that I never knew that I never knew.

“Self-Portrait,” 1955. Ruth Smith. Courtesy Phillips Collection.